Sarah Stopforth, Vernon Gayle, and Ellen Boeren discuss the enduring nature of social class-based inequalities in the UK and demonstrate the magnitude of the gap between pupils from the most advantaged and those from the less advantaged social classes.

GCSE results day is now an annual newsworthy event. Every August we watch live broadcasts of nervous young people opening envelopes containing their examination grades. This year, the annual TV ritual takes place in the midst of the unfolding crisis surrounding results in school qualifications during the COVID-19 pandemic and the cancellation of examinations.

GCSE results are important because they shape young people’s choices and chances in education, training, and the labour market. Here we wish to draw attention to the effects of parental (or family) social class on pupils’ school GCSE attainment. News items on gender differences in results, or on gender participation in different subjects, are common. Some media reports focus on inequalities in results for pupils from different minority ethnic groups. By contrast, the media very rarely reports on the sizeable and persistent parental social class differences in school GCSE outcomes.

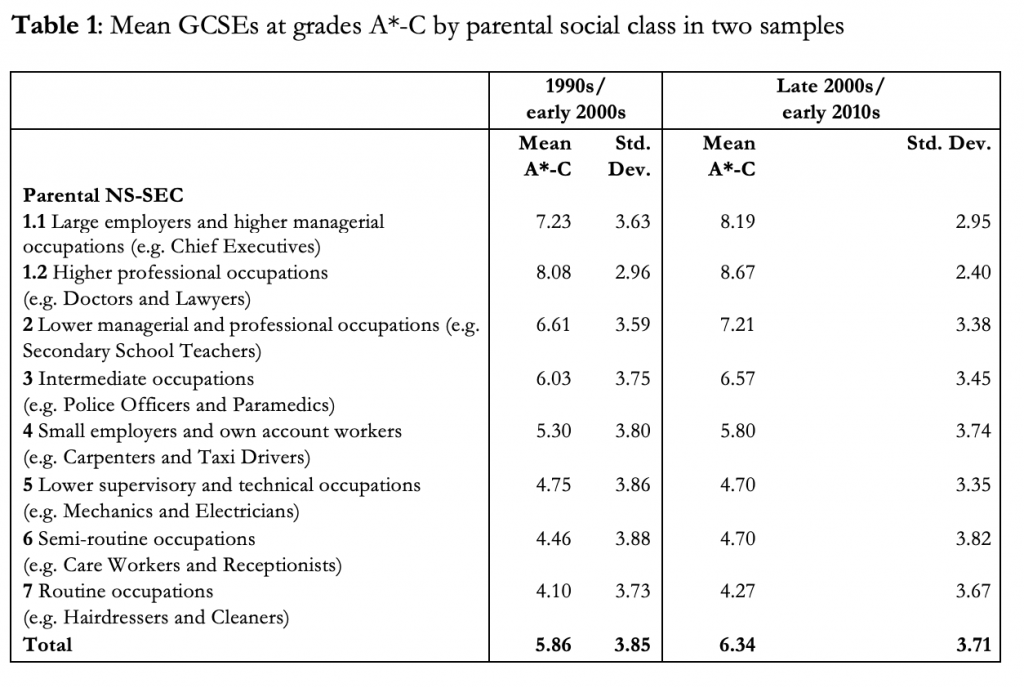

In a recent study, we examined the relationship between parental social class and pupils’ school GCSE results over two decades. We found remarkable consistency in social class inequalities, despite the overall improvement in GCSE results. We used two large scale, nationally representative household panel studies: the British Household Panel Study, and Understanding Society to which administrative GCSE data can be linked from the National Pupil Database. Together, these two data sources provided a unique 22-year window of observation from the early 1990s to the early 2010s. GCSE subjects in this period were graded from A* to G, with A*-Cs considered ‘good’ passes.

There are many approaches to measuring social class. In our study we used the official UK National Statistics Socio-Economic Classification (NS-SEC). This is an occupation-based social class measure in which members of a social class are considered to share a similar ‘market situation’ (e.g. levels of income, economic security, and chances for economic advancement), and a similar ‘work situation’ (e.g. authority and control). Members of a social class have similar lifestyles and comparable life chances. There are eight NS-SEC class categories, with more advantaged classes such as higher professional occupations (e.g. doctors and lawyers) at the head of the scheme, and less advantaged classes such as routine occupations (e.g. hairdressers and cleaners) at the foot of the scheme.

We found that pupils with parents in higher professional occupations on average gained eight GCSEs at grades A*-C, compared with pupils in routine occupations who on average gained only four (see Table 1). Alarmingly, many pupils in less advantaged social classes also fell short of the national policy benchmark of five or more GCSE passes at grades A*-C.

Sources: 1990s/early 2000s sample uses data from the British Household Panel Survey (n=1624); and late 2000s/early 2010s sample uses data from Understanding Society with linked National Pupil Database (n=1175). Std. Dev. is standard deviation of the mean.

Sources: 1990s/early 2000s sample uses data from the British Household Panel Survey (n=1624); and late 2000s/early 2010s sample uses data from Understanding Society with linked National Pupil Database (n=1175). Std. Dev. is standard deviation of the mean.

Parental social class effects were important even when additional influential factors such as parental education, gender, housing tenure, ethnic group, and school-year cohort were included in the analyses. Young people from less advantaged social class backgrounds not only struggled to attain any GCSEs at grades A*-C, but those that did overcome this initial hurdle were then also much more likely to miss the policy benchmark of five or more ‘good’ GCSE passes.

Although GCSE results have improved over time, there is still a persisting gap between pupils from the most advantaged and less advantaged social classes. The results in our study convince us that the effects of parental social class are nuanced and would not be adequately captured by simple proxy measures such as Free School Meals eligibility, or geographical measures of deprivation. Social class inequalities at the individual level continue to be a key determinant of education outcomes for some of the most contemporary cohorts of young people in England.

It is difficult to predict how the specific problems associated with the cancellation of exams will be resolved. The situation has, however, exposed existing socio-economic inequalities in the education system. In the five decades since the introduction of comprehensive secondary schools there have been a raft of policies introduced to tackle social inequalities. Despite changes to the curriculum, assessment, qualifications, and the structure and organisation of schools, parental social class continues to affect educational outcomes.

The enduring nature of social class based inequalities is troubling enough, but the magnitude of the gap between pupils from the most advantaged social classes and those from the less advantaged social classes is deeply concerning. It is especially alarming that many pupils from the least advantaged social classes do not even achieve the benchmark of five GCSEs at grades A*-C.

____________________

Sarah Stopforth is a Research Fellow at the University of Sussex.

Vernon Gayle is Professor of Sociology and Social Statistics at the University of Edinburgh.

Ellen Boeren is Professor of Education at the University of Glasgow.

Photo by Dee @ Copper and Wild on Unsplash

Is there any significance in the slightly lower results for Large employers than higher level professionals?