In Canada last week, Stephen Harper’s Conservative government was defeated by a motion of no-confidence which declared the government to be in contempt of Parliament for its refusal to share information that opposition members had requested to properly assess legislation put before them. This lack of transparency has a history, argues Anne White, and may offer some lessons and a warning for David Cameron’s Conservative government on this side of the Atlantic.

In Canada last week, Stephen Harper’s Conservative government was defeated by a motion of no-confidence which declared the government to be in contempt of Parliament for its refusal to share information that opposition members had requested to properly assess legislation put before them. This lack of transparency has a history, argues Anne White, and may offer some lessons and a warning for David Cameron’s Conservative government on this side of the Atlantic.

The blogosphere is now ripe with debate, charges and more passion than I thought PM Harper and opposition leader Michael Ignatieff could elicit in Canadians. And yet the polls are clear that Mr Harper will win another minority government – indeed, reports from door knocking indicate the Canadian electorate is not at all interested in having this election.

Philip Blond, architect of the Big Society, has been in Canada recently, hoping to sell the Big Society to Red Tories on that side of the pond. He too has found that not much has changed from traditional party lines; “the left arguing for higher welfare – the right for fiscal stability.”

So why an election?

The battle is largely cerebral and of great interest to policy wonks and constitutional experts with only a sprinkle of policy announcements to engage the electorate. And, it has resulted from a (relatively unstable) minority government’s experience with promoting transparency on the one hand and then rescinding it in an effort to maintain governing ability on the other.

Friday’s defeat was not the first time parliament voiced concerns over transparency in Mr. Harper’s government. The Information Commissioner and Parliamentary Budget Officer have all clashed with the government in recent years over complete lack of and/or delayed transparency. The final straw which brought the government down was months of Freedom Of Information requests for the details of costs on crime bills, corporate tax cuts and the planned purchase of F-35 fighter jets. And all this from a government that was elected on a promise to increase transparency.

The Parliamentary Budget Office, in fact, was created as part of that very initiative to keep the government to account. Three years on, however, the shine from that measure has worn dull as a result of limited resources and ongoing stonewalling by the Conservatives due to ”Cabinet confidences” .

It is this point which is most salient for the UK. The coalition government has promised increased transparency, and in many ways it has delivered; Whitehall departments are publishing business plans online, councils are now publishing all contracts over £500, the Cabinet Office has published organisational charts, full disclosure of all central government spending and contracts over £25,000 is required… the list goes on.

In theory, these transparency initiatives are a welcome step in the right direction towards greater government accountability. Departments are made more accountable in each functional area and the public can track progress, costs and (as the fiscal consolidation unfolds) changes in how the government at all levels interacts with its Big Society suppliers.

Unfortunately, the data is either not yet widely available, incomplete or, most worryingly, in an unstandardized and more or less unusable format. For example, organisational charts show only 60 per cent of departments provide data which allow analysis of full time equivalent (FTE) counts with salaries at detailed functional levels. A full 40 per cent provide aggregate data for FTE grades and salaries at programme level or higher, making comparative analysis of detailed areas like media or press relations impossible across departments. The charts need to be standardised for clear readability across departments and salary ranges published for each grade in every department. Currently, the information is very inconsistent and many departments provide insufficient detail to compare across departments. Additionally, special advisor data (first published in June) has not been incorporated to the organograms and sits on a different site.

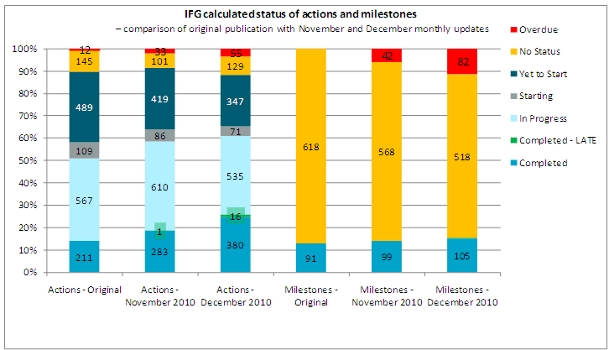

The “business plans” (aggregate measures of each department’s “to do” list) pose similar problems with 518 of the December 2010 milestones reporting no status (Figure 1). The government initially envisioned an army of locally based “armchair auditors” to monitor this type of information – in reality, for the most part, it is institutions (in this case the Institute for Government) that have the benefit of expertise, time and capacity to undertake the onerous task of keeping the government to account by tracking and publishing updates.

Figure 1: Government Business Plan Analysis

Source: Institute for Government

The Freedom of Information Act is up for review as well but with no intention to reassess the ministerial veto. In any case, evidence of a post-it note culture, where sensitive information is recorded on easily removable and undocumented sticky notes, exists already.

For the general public, then, the transparency agenda in its current form provides little more than fodder for dinner conversation about top civil servants’ exact salaries, the state of unmet goals and ad-hoc commentary that the media, researchers and others (who have the time) put into the public sphere.

A transparency agenda of this sort, without committed resources and budget to make that transparency usable by the public to keep government to account, let alone the legions of new Big Society service providers the government envisions, is a perilous venture.

Joe Public can be proactive in the determination of his public services, and should be. But the idea of Amazon type sites for more transparent and accountable public service delivery needs Amazon type infrastructure, standardization and monitoring or regulation – for complex public services – not just books. The success, or failure, of the Big Society vision depends upon it.

The coalition government is already facing criticism for the failure to keep the transparency agenda moving forward. And experience shows that mature governments are severely challenged, at times regretful, of opening the books too quickly, too naively:

Freedom of Information. Three harmless words. I look at those words as I write them, and feel like shaking my head till it drops off my shoulders. You idiot. You naive, foolish, irresponsible nincompoop. There is really no description of stupidity, no matter how vivid, that is adequate. I quake at the imbecility of it.

Once I appreciated the full enormity of the blunder, I used to say – more than a little unfairly – to any civil servant who would listen: Where was Sir Humphrey when I needed him? We had legislated in the first throes of power. How could you, knowing what you know have allowed us to do such a thing so utterly undermining of sensible government?

Tony Blair, A Journey, Hutchinson, September 2010

With such revolutionary changes being adopted in Britain and so much resting on transparency as the solution, the government would be advised to take a quick look across the pond at this time lest these transparency initiatives come back to haunt them.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.