Government ministers have appointed over 260 policy tsars since May 1997. Tsars are privileged players in the policy drama, handpicked by ministers and given direct access to them and senior officials. Although policy tsars lack imperial force, they can be hugely powerful advisors. Potentially each tsar has the power to influence ministers and policies directly and personally, and many of them have used this power strongly. Until Dr Ruth Levitt and William Solesbury did detailed empirical research on tsars, no-one seemed to know the scale or scope of these appointments nor what difference they have made.

When the Public Administration Select Committee first said in 2010[1] that there was “little transparency concerning the informal and ad hoc appointments made by government”, it could not underpin its concern with thorough or independent research about the tsar phenomenon. The Coalition government was largely dismissive of the committee’s recommendations at the time, even though it too was in the dark about the extent or impact of the advice that tsars provide. Indeed, governments still do not keep a central record of these appointments despite PASC recommending this.

We first contacted the Cabinet Office about our research on tsars in the Spring of 2012 but the Prime Minister and Cabinet Office Minister were still claiming in August that policy making was an internal monopoly. Francis Maude even proclaimed that: “For the first time ever [our emphasis] ministers are directly commissioning policy advice from outside Whitehall moving towards our goal of opening up policy making.” [2] PASC has just repeated [3] the call for greater transparency in ad hoc appointments made by governments. Our empirical evidence brings tsars out of the shadows for the first time.

Tsars hit the headlines from time to time. After the recent shambles over the West Coast rail route franchise decision, the new Transport Secretary picked Richard Brown, Chairman of Eurostar, to look at the whole rail franchising process. Earlier in the year Adrian Beecroft, a hedge fund manager and large donor to the Conservative Party, recommended loosening employment protection law. Tom Winsor, lawyer and former rail regulator, recommended changes to police force terms and conditions. Many other tsars are barely visible. What is their role making public policy?

They are advisors: individuals from outside government (though not necessarily from outside politics) who are publicly appointed by ministers to advise them on policy on the basis of their expertise. Tsars exist alongside other sources of external expertise that governments draw on, such as expert committees, consultants and researchers, commissions of inquiry, think tanks, professionals like lawyers or economists, and other informal advisers, including journalists, whom ministers and civil servants frequently chat to.

The Cabinet Office does not keep a central record of tsars. The prevailing view is that they are insignificant in numbers and cost and often useful. Our recent research at King’s College London shows a different story on numbers. We have identified over 260 tsar appointments made by ministers since 1997.

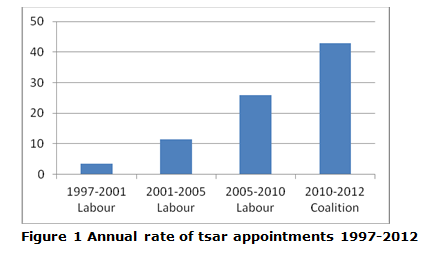

The annual rate has risen dramatically through the three New Labour administrations and the Coalition, whose ministers had so far appointed over 90 tsars up to the end of July 2012. It is high time to recognise that tsars, along with ministers, officials and special advisers, are part of the central government architecture of policy making.

Tsars complement traditional sources of external expertise for policy development. In practice the commission of inquiry is much more rare now; budgets for hiring consultants and researchers are under tighter control, and the Coalition’s bonfire of the quangos is slimming the numbers of advisory bodies. Meanwhile tsars are willing, available and highly flattered to be asked to give ministers ideas and suggestions to tackle pressing concerns, for example Professor Alison Wolf on vocational education and Sir Scott Baker QC on extradition laws. Tsars can also help by reframing issues to provide innovative thinking on seemingly intractable problems. Adair Turner on pensions or Andrew Dilnot on social care are examples. Another way tsars contribute is by informing the terms of policy debate, as Sir Nicholas Stern did with the economics of climate change.

Ministers clearly like this way of getting expert advice. Our research shows that they find it speedy (6 to 12 months is the common turnround), cheap (tsars work part-time and are often unpaid), informal (most tsars are already known by or known of by the minister who appoints them), authoritative (most tsars have existing reputations in their own field, some are already public figures) and reports come direct (rather than via officials). However, tsars are not at all diverse: 85% were males, 83% were over 50 when appointed and 98% were ethnically white.

Some appointments have a political purpose, whether seeking to neutralize anticipated criticism (such as the Coalition inviting Frank Field MP to advise it on poverty and life chances) or to thank ministers just reshuffled out of office (as when Gordon Brown appointed former Sports Minister Richard Caborn MP as Ambassador for the 2018 World Cup). Ministers also appoint high profile figures to tsar roles to add a bit of glamour and generate useful PR: David Cameron and Nick Clegg jointly asked Mary Portas to review the future of the high street. PASC had already commented: “The allegation that some of these posts might have been created for the sake of a press notice may be unfair, but it is difficult to refute without greater transparency.” [4]

In our view tsars are here to stay. They can play a useful role in policy development. So it is imperative that their recruitment, terms of reference, payment, access, approach and reporting are made much more transparent, while retaining the informality that is benign. This should help to ensure both propriety and effectiveness. At the moment neither the Commissioner for Public Appointments nor the Cabinet Office oversees tsars. Ministers and departments make it up as they go along and actual practices vary wildly. About 20% of tsars did not produce a published report, and not all reports received a published ministerial response. Nor is there any accumulation of experience about tsars, either within each department or across departments.

It is time to sort this out. We need more transparency about tsar appointments, their remits, their conduct and progress, their outputs and effectiveness. Our recommendations would help to bring the tsar phenomenon out of the shadows.

[1] Public Administration Select Committee, Goats and Tsars: Ministerial and other appointments from outside Parliament, Eighth Report of Session 2009–10, HC 330.

[2] Cabinet Office, Looking abroad for next steps in Civil Service Reform Programme, Press Notice CAB 073-12, 11 August 2012.

[3] Public Administration Select Committee, Special Advisers in the Thick of it, Sixth Report of Session 2012-13, HC 134, para 55.

[4] Public Administration Select Committee, Goats and Tsars: Ministerial and other appointments from outside Parliament, Eighth Report of Session 2009–10, HC 330, para 101.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Dr Ruth Levitt and William Solesbury, Visiting Senior Research Fellows, Dept of Political Economy, King’s College London