Anastasia Ershova and Sebastian Adrian Popa explore the extent to which the public could be encouraged to comply with COVID-19 restrictions based on how effective they think those were abroad. They find that intention to comply with policies is indeed influenced by overseas practices and their perceived effectiveness. They also find that UK residents are quite aware of how effective policies implemented abroad are relative to those in place in the UK.

Anastasia Ershova and Sebastian Adrian Popa explore the extent to which the public could be encouraged to comply with COVID-19 restrictions based on how effective they think those were abroad. They find that intention to comply with policies is indeed influenced by overseas practices and their perceived effectiveness. They also find that UK residents are quite aware of how effective policies implemented abroad are relative to those in place in the UK.

The COVID-19 pandemic has rekindled interest in studies looking at why individuals comply with policy measures. We know, for example, that there is remarkable variation in compliance with different measures as well as across age groups, with younger people being less likely to follow government regulations. Other studies have maintained that self-reported compliance has been driven by social norms rather than by knowledge or concern about catching the virus.

What lacks is a study of the potential effect of experience, success, or failure abroad on compliance within a country. To answer this question, we rely on survey data collected by Ipsos MORI’s online random probability KnowledgePanel between 10-16 December 2020. In a context where developments in other countries impact on evaluations of domestic actors, and policy measures across countries are fairly similar, we ask whether learning about policy successes and failures abroad impacts on compliance with policies adopted in the UK. We expect that the perceived effectiveness of policies elsewhere does reinforce an individual’s resolve to follow a potentially unpopular and restrictive measure at home.

The first step in answering this question is to show the degree to which members of the public are aware of the effectiveness of COVID-19 measures elsewhere. On the one hand, given the high frequency of news stories about developments abroad – a search on LexisNexis finds over 50,000 BBC articles about COVID-19 published between March and November 2020 – we anticipate that the public are generally aware of the situation overseas, and that they can compare it to that in the UK. On the other hand, news-saturated environments can create an information overload, hindering the effective processing of information and causing psychological discomfort. The challenges posed by this overload can then shift public attention from what is happening abroad to the domestic arena only.

By relying on objective measures of countries’ performance in containing the spread of the virus, we find that most respondents have a pretty good grasp of how other countries were handling the pandemic compared to the UK (Figure 1). This is especially the case for countries that are clear examples of either successful (i.e. Australia and China) or particularly deficient (i.e. USA) practices. The picture is more nuanced when it comes to handling the economic consequences of the pandemic (see light blue bars in Figure 1). Respondents could only identify the countries that did better in handling the economic effect of the pandemic if those countries also did better in containing the virus, which suggests a spill-over effect across policy dimensions. Overall, as Figure 1 summarises, the accuracy of perceptions varies substantially between policy areas.

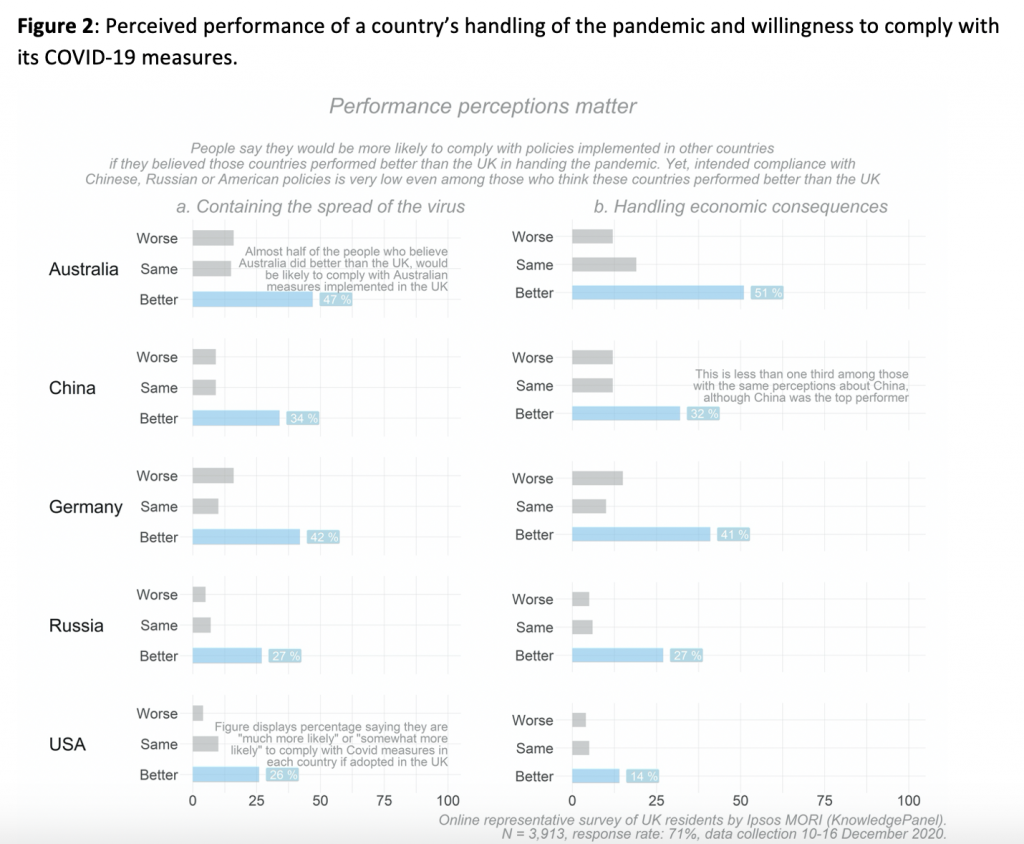

Nevertheless, this does not necessarily mean that knowledge about another country’s performance will translate into policy compliance. Under normal circumstances, one may turn to the past to evaluate the policy in place. But since this is not an option in the unprecedented case of COVID-19, other countries can act as benchmarks for individuals in relation to evaluating the situation in their own country. In a context where we already know that response to COVID-19 abroad influences the evaluation of incumbents in one’s home country, we can expect that country benchmarks relating to handling the pandemic could also impact compliance with such measures (see Figure 2).

Our results offer support to this observation: respondents who believe that a foreign country handled the pandemic better than the UK show more willingness to comply with policies adopted in those countries. A pattern also emerges when we disentangle the perceptions of effective economic response and the measures aimed at pure containment of the virus. In both areas, we find a higher proportion of people willing to follow policies that they perceive as being more effective in addressing the crisis. The important addendum here is that using examples of effective practices from democracies which succeeded in curbing the spread of the virus seems to have a stronger impact on stimulating compliance, even if some policies adopted by these democratic states, such as Australia, were more restrictive than those adopted by authoritarian states like China.

The patterns above may have implications for policy learning. As our results indicate, public compliance with COVID-19 measures goes hand in hand with their perceived effectiveness. Unlike other studies, we demonstrate the extent to which intention to comply with policies is influenced by overseas practices and their relative perceived effectiveness. This is particularly important in a context where COVID-19 fatigue and the recent positive developments around vaccines can lead to a decrease in compliance.

Our results may also have wider application. They suggest that examples of good practice from other democratic countries could be used to gain support for harsh economic policies that would otherwise be considered widely unpopular, though policymakers should also account for any spillovers of policy evaluations across different domains of crises-induced policies. Policymakers should engage with this result closely and attempt to incorporate the examples of policy successes from other democracies when introducing restrictive or potentially unpopular measures in their home countries.

Anastasia Ershova is Postdoctoral Researcher in the Institute of Political Science at Leiden University.

Anastasia Ershova is Postdoctoral Researcher in the Institute of Political Science at Leiden University.

Sebastian Adrian Popa is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Politics at Newcastle University.

Sebastian Adrian Popa is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Politics at Newcastle University.