Despite the overall drop in COVID-19 deaths, the latest data reveal continuing increases occurring in care homes and the community. Melanie Henwood explains why there is a need for more scrutiny around what is happening in care homes and across the social care system.

Despite the overall drop in COVID-19 deaths, the latest data reveal continuing increases occurring in care homes and the community. Melanie Henwood explains why there is a need for more scrutiny around what is happening in care homes and across the social care system.

The latest weekly death data released by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) up to 24 April show a drop in overall deaths (all causes) compared with the previous week. It is also the first week in which there has been a fall in deaths since March 20, but the weekly total of 21,997 deaths is still almost double the five-yearly average for this time of the year.

Some of these ‘excess deaths’ are directly attributed to Covid-19: 8,237 death registrations mentioned the virus in the week to 24 April, accounting for 37.4% of all deaths. The impact of these deaths is not spread evenly across the population, and the highest number of Covid-19 deaths occurred among people aged at least 85 (42.6% of all Covid-19 weekly deaths).

Where are deaths occurring?

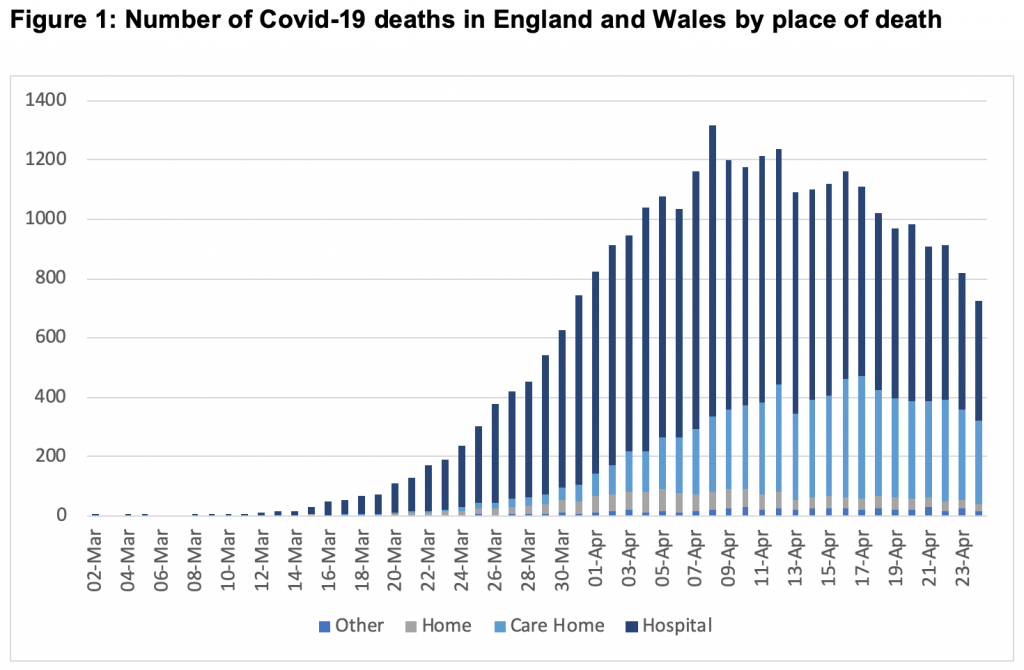

Where deaths are occurring reveals the most about how the pandemic is developing. The ONS year-to-date analysis tracks deaths by the week and cumulatively. Up to week 17 (ending 24 April) the data for Covid-19 deaths indicate that 71.8% (19,643) occurred in hospital, while the remainder occurred in the community: 5,890 in care homes; 1,306 at home; and 301 deaths in hospices.

But the week-to-week changes reveal more granularity. In just one week (between week 15 and 16) the total deaths in care homes increased by 48%, representing almost a third of all deaths. Figure 1 shows the number of Covid-19 deaths in England and Wales registered up to 24 April by place of occurrence, and demonstrates the shifting pattern of hospital deaths declining and those in the community, particularly care homes, still rising, and equivalent to almost 60% of those occurring in hospitals

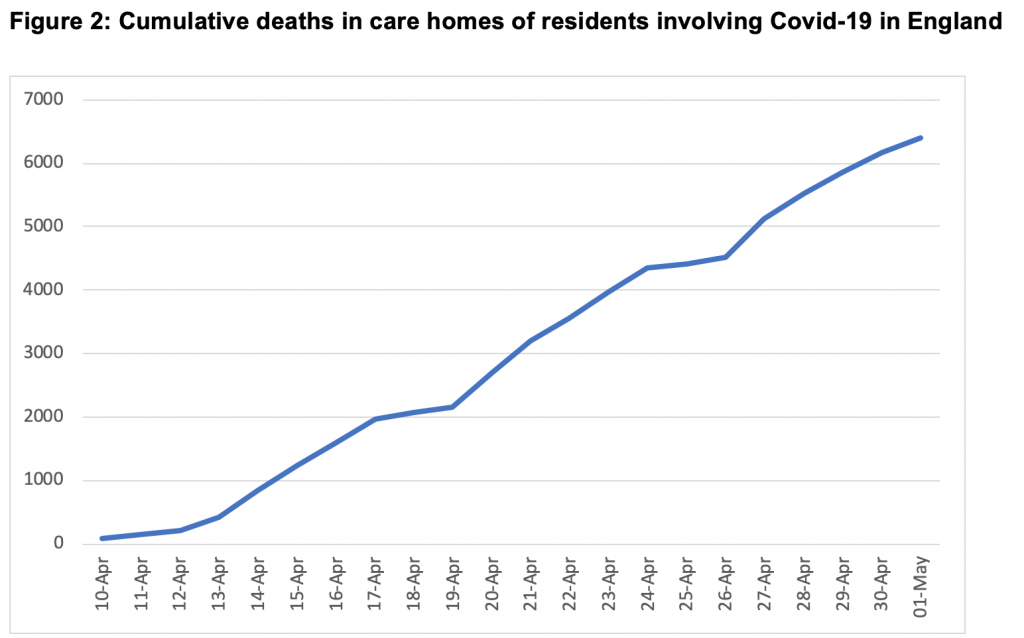

Since 10 April, the Care Quality Commission has been collating data on notifications of deaths of residents in care homes where Covid-19 was believed to be involved. Figure 2 shows these cumulative deaths from 10 April to 1 May. The continuing upward trajectory is stark.

The government’s lack of response

Despite the compelling evidence about the rising deaths in care homes, the response from government has been remarkably laissez-faire. On the day that the data showing sharp rises were published (28 April), Matt Hancock remarked – to some astonishment – that ‘the proportion of Coronavirus deaths in care homes is around a sixth of the total, which is just below what we see in normal times’. This is baffling. Deaths in care homes, both from all causes and Covid-19 mentions, are increasing; what the ‘sixth of the total’ refers to is not clear, nor is it clear why the Health Secretary concluded this is below what would ‘normally’ be expected. Given the opportunity in questions to correct this glaring error, Hancock dismissed the issue. Rather, he re-stated that care homes have been a top priority from the start, but that it was recognised there would be challenges because of the frailty of residents. A failure to understand the data, to interpret it correctly, or to present a credible strategy for responding to the emerging pattern is inept at best.

Prime Minister’s Questions on 29 April saw the First Secretary (Dominic Raab) responding to Sir Keir Starmer asking about the deaths in care homes and the ‘truly dreadful’ figures emerging. Raab claimed – again despite the latest evidence to the contrary – that there ‘are some positive signs’ emerging about deaths in care homes. He also referred to the principal challenge in care homes of a decentralised system and lack of control of ‘ebb and flow’ in and out of homes of residents, staff, friends and family as ‘the single biggest challenge in terms of reducing transmission’.

It is wrong, and misleading, to offer a post-hoc rationalisation of the situation merely as the result of a marketised care system which does not operate like the command and control world of the NHS. In response to the challenge, Raab reiterated that there is a ‘comprehensive plan’ to ramp up testing in care homes (announced on 28 April), to overhaul the way personal protective equipment (PPE) is delivered, and to expand the workforce by more recruitment. That looks like a plan that could have made sense several weeks ago, but at this stage of the pandemic it is too late; the upsurge in community deaths reflects the failures of the past four weeks to prioritise social care, or to take any account of how it might be impacted by the decisions made for the NHS.

It might have been expected that there would be some humility, or some acceptance that the dire situation in care homes and the community is a consequence (even if unintended) of the policy to-date in responding to the pandemic. But this was entirely predictable, and therefore – to some extent – avoidable. The focus has been on the NHS from the outset; it is there in the slogan to ‘protect the NHS’ and the imperative to ‘flatten the curve’ of transmission so that the NHS is not overwhelmed. The increase of surge capacity through emptying hospitals of patients wherever possible, and creating new ICU facilities in the pop-up Nightingale Hospitals, also meant that additional pressures in the system would be pushed elsewhere. They have emerged in the community – people were discharged from hospital to care homes without testing for Covid-19; people who became ill in care homes were largely not tested for the virus and most were not admitted to hospital. With inadequate PPE provision, all the preconditions were in place for the rapid and uncontrolled transmission of the infection within care homes and across the social care system in the community. This is the price of protecting the NHS at any cost.

The Prime Minister has spoken of the ‘current success’ of the response to coronavirus, but this does not look like success when the death toll is currently the highest in Europe. We are not yet out of this crisis by any means, but the growing difference between what is happening in the NHS and the fate of people effectively abandoned in social care has to be addressed and responsibility accepted. In a massive understatement at the daily briefing on 5 May, after presenting the latest data on place of death and noting that around half as many deaths are now occurring in care homes as in hospital, the Chief Scientific Adviser of the Ministry of Defence, Professor Angela Mclean remarked: ‘I think what that shows us is that there is a real issue that we need to get to grips with about what is happening in care homes’.

At Prime Minister’s Questions on 6 May, Sir Keir Starmer quoted this observation and asked why the government had not already got to grips with the situation in care homes. Boris Johnson responded that the situation is something that he bitterly regrets but that people are working very hard to get the figures down and to get the right PPE to care homes and to ‘encourage workers in care homes to understand what is needed’. However, he challenged the conclusion about the state of the epidemic in care homes and claimed ‘palpable improvement’ in the figures. That remains to be seen; the deaths are increasing slower but are rising nonetheless, and there is little sense of this being addressed strategically or treated as a priority. Failure to do so, and to continue to view social care as a different level of challenge because of the frailty of many older people needing care, would seem to suggest, at best, complacency. At worst, it hints at indifference, reflecting inbuilt ageism and acceptance of the inevitability of the scale of deaths outside hospitals as a price worth paying.

_____________________

Melanie Henwood is an independent health and social care research consultant.

Melanie Henwood is an independent health and social care research consultant.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: by Bret Kavanaugh on Unsplash.