Being the UK Prime Minister is about far more than looking good on TV and being unflustered in the Commons at question time. There is an essential policy co-ordination and policy motivation role to the office, which must be taken seriously if what government does is to cohere to an integrated whole. Yet after 16 months in power, Patrick Dunleavy has serious doubts about David Cameron’s ability to make public policies that work. He seems to be running an eclectic, ‘ring donut’ government of barons and caretakers, where Tory ministers are left free to create incoherent policies – while Cameron’s attention is focused only on keeping the Coalition afloat.

Being the UK Prime Minister is about far more than looking good on TV and being unflustered in the Commons at question time. There is an essential policy co-ordination and policy motivation role to the office, which must be taken seriously if what government does is to cohere to an integrated whole. Yet after 16 months in power, Patrick Dunleavy has serious doubts about David Cameron’s ability to make public policies that work. He seems to be running an eclectic, ‘ring donut’ government of barons and caretakers, where Tory ministers are left free to create incoherent policies – while Cameron’s attention is focused only on keeping the Coalition afloat.

David Cameron is a successful political leader, one who has been very assured in his public persona (barring the odd incident apparently patronizing women MPs) and consistently confident in his Commons performances. But as Prime Minister, he has notched up rather limited political accomplishments, so far. Conservative support in all the polls for the last six months has lurked in the region of 36 to 38 per cent and remains stuck there – essentially at the level that Cameron obtained back in the 2010 general election. This looks good by comparison with the trauma being experienced by the Liberal Democrats, but Labour’s ratings have revived to a level where they could today enjoy a comfortable overall majority of 20 to 50 seats in a newly elected Commons.

Of course, governments in mid-term are unpopular, but even the Tories most core supporters seem increasingly sustained more by tribal loyalties than any government achievements. Recently, the right-wing commentator Richard Littlejohn wrote a column in the Sun under the heading: ‘So what have Dave’s Tories done for you?’ He seemed unable to find much of an answer and he found scraps of solace only in the most obscure issues – for example, at least the M4 bus lane had been scrapped.

Within the government itself, Cameron’s greatest success has been to bind the Liberal Democrats into the coalition on terms that increasingly seem to be threatening the party’s continued existence as an independent political force. Because Clegg chose not to have a substantial department, and Danny Alexander plays second fiddle to George Obsorne at the Treasury, the Liberal Democrats actually run just three departments of state – BIS (although Cable is hedged in here by Willetts on universities), DECC (where Chris Huhne does a steady job), and Scotland (where Michael Moore is almost unknown, even to politics geeks). This is an insubstantial set of franchises set against the Tories 18 members with meaty departments. The Liberal Democrat influence on the government as a whole has consequently been widely seen by voters as marginal.

The root of David Cameron’s achievement here lies in the Coalition Agreement signed in June 2010, which has become a long-term blueprint for government policy that is both remarkably short and un-detailed (compared to normal party manifestos) and exceptionally hard to vary or break away from. Everything in the Agreement is partitioned to one of the two parties, and so everything itemized must get done – or the continued existence of the coalition itself would be jeopardized.

Yet Cameron’s greatest failures as Prime Minister also stem from the same source, because he and the Number 10 staff have had to commit so much time and energy to maintaining Clegg’s illusions of influence, to persuading him that being Deputy Prime Minister is not a non-job, and that his tiny band of political ingénues are making a difference to outcomes and policy. The inevitable consequence has been that that Cameron’s ability to influence the much more experienced and powerful Conservative members of his team has been unusually slender. Where they were barons in the Tory party before government, many leading Conservative ministers have been even more baronial and left to their own devices – so long as they stick within the Coalition Agreement’s terms.

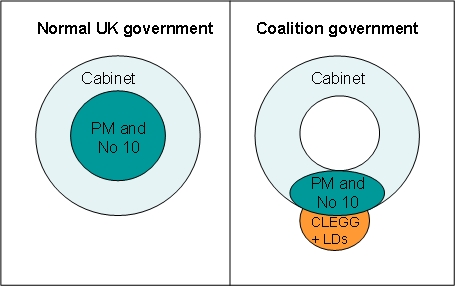

And where the new ministers were placeholders, they have been caretaking their departments in almost equal isolation – focusing their energies simply on delivering expenditure cutbacks to fit the Osborne-Alexander agenda. The result has been a ring-donut government, with a hollow centre. Much of the Prime Minister’s activities have been concentrated on a range of often minor issues where Clegg and the Liberal Democrats are trying to assert themselves or to stop Tory ‘big beasts’ secure in their departmentals from trampling across red lines in the Coalition Agreement. As a result there has been far weaker than usual control by Cameron and Number 10 over the dominant Tory cabinet members, shown in my chart below.

Chart 1: How the coalition differs from a normal UK government

In sixteen months this ‘ring-donut’ pattern of government has chalked up some spectacular failures to integrate policies, including:

- The largely unconstrained trajectory of Andrew Lansley at the Department of Health, who launched off for months in isolation on an expensive root and branch reorganization of the NHS (costing at least £3.5 billion), one which threatens to disrupt for at least three years the absolutely critical relationships between NHS healthcare and local authority social care;

- The astonishing gulf between the Conservative’s initial dismissal of Labour’s government IT schemes, and the decision by Ian Duncan Smith at the Department for Work and Pensions to commit to creating not just a universal benefit integrated across many different DWP benefits, but a universal credit integrating most of DWP’s operations with those of the tax agency (HMRC). While Francis Maude at the Cabinet Office has spent 16 months turning down IT contracts and demanding savings from IT contractors, the ambition and difficulty of the universal credit idea has grown to titanic proportions.

- The policy mess at the Department of Justice, where Ken Clarke took the completely unrealistic projections for cutting his department’s budget, and almost made them work by pushing for a big reduction in the prison population – only for Cameron to veto the plan after a year’s work, because the Tory right were up in arms. The post-riots crackdown has compounded the problem by boosting prison populations to record levels – and on current form the spending plans cannot be realized.

- The chaos at the Ministry of Defence, where our last aircraft carrier was scrapped only for the UK to commit a matter of weeks later to a Libyan air campaign for which a carrier would have come in very handy. Meanwhile long term non-plans envisage building two bigger carriers, mothballing one immediately, then using the other one for many years without any fixed wing aircraft;

- The proposals to privatize state-owned forest land, no sooner floated by Caroline Spellman than canned because of howls of protest from core Conservative interests in the countryside – a process that is seemingly being repeated with the proposed liberalization of planning controls.

- Lastly, and most seriously, the over-squeezing of public expenditure, combined with the talking up of economic pessimism by the Chancellor and Chief Secretary – a fiscal blow which hit an already fragile UK economy like a truck, slowing growth to zero in record time. As the global economic outlook worsens, this misplaced attempt to over-play the political business cycle is now stretching the period of near recession out for several years to come, while the Treasury ministers seem to be in denial about the damage already done.

In a normal, single-party government it is hard to see that this list of reversals and disasters could have grown so long so quickly. A more effective Number 10 machine should have quickly stomped on more or less all of this list, barring the failure to control the Chancellor – which has been a recurring problem for several previous premiers back to Margaret Thatcher. In every case listed above Cameron has come to the issues too late, months behind the curve in policy-making, weakly informed on policy choices and options, fighting a rearguard action triggered by Liberal Democrat or Tory backbench reactions. So Lansley’s ‘reforms’ survived (despite getting record levels of no confidence from health professional bodies). Forest privatization was pulled. Defence, prisons and the economic strategy rumble on unresolved and incoherent.

These seem to be the hallmarks of a premier who is weak in policy grip and in the institutional support for his policy education. Cameron seems too distracted by the politics of day-to-day and coalition issues to create any coherent agenda for government – beyond cutting back the state and hoping for the best (not a bad summary of the meaning content of the Big Society). The coalition has survived, but its policies across very large and critical areas seem incoherent and un-integrated.

Above all, Cameron’s governance strategy, his statecraft, the ways in which the government intends practically to see its value and ambitions implemented, seem weak. As I have written in an earlier blog, the urban riots this summer in London and other cities acutely demonstrated the vulnerability of the British state, grounded in ministers’ inability to accept that they must actively engage most of the public sector staff in positively striving to realize clear policy goals. Cameron’s hurried return from vacation to the London riots firestorm – a situation that slumped into an acute crisis of governability in a matter of days – signalled an underlying casualness about Conservative ministers, a breezy conviction that somehow governance was easy. The British state has many resilient features, all of which swung into action after an initial lag to close down the riots threat. But the over-reaction in the post-riots arrests and the deforming of the judicial system, along with Cameron’s refusal to really learn any lessons from the crisis, have all stored up trouble for the future.

With the escalating economic gloom in Europe and the USA, the hollowness of Cameron’s premiership gives few reasons for optimism about the coming political year. As the Tories wend their way home from a disappointing conference, comforting themselves only with the aura of ‘responsibility’ and glee at the Euro’s troubles, public appreciation of the need for clearer policy leadership, better government and a positive improvement strategy for Britain’s society and economy seems likely to grow. The immediate future is that inflation continues to rage unchecked (at least until January), family incomes are being eroded and the economic impetus in many UK regions is dwindling. It will be a good thing if not too many firms and households decide to pay down their debts, as Cameron’s conference speech draft initially suggested in ‘leader-of-the-opposition’ mode, or the run-up to Christmas could be even bleaker than before.

Please read our comments policy before posting.