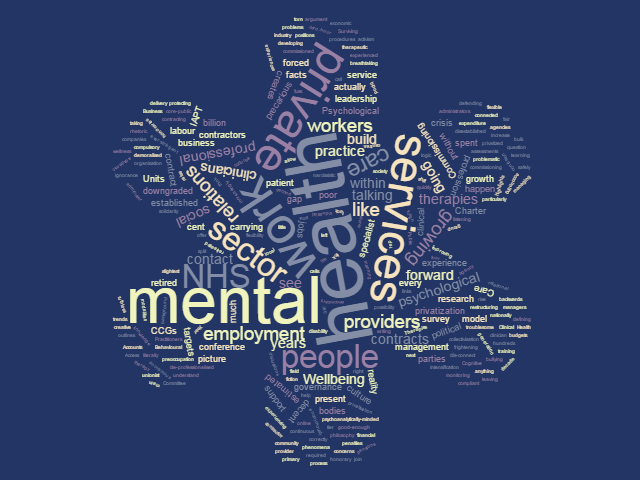

Recently, Elizabeth Cotton attended a mental health conference to join a group developing a Wellbeing Charter for people working in psychological therapies. Coming to mental health from industry, she found the lack of knowledge about the trends in the sector breathtaking and frightening. Here, she outlines the problematic role that privatisation of services is playing, and highlights a survey which aims to build up a picture of the facts of work in the mental health sector.

Recently, Elizabeth Cotton attended a mental health conference to join a group developing a Wellbeing Charter for people working in psychological therapies. Coming to mental health from industry, she found the lack of knowledge about the trends in the sector breathtaking and frightening. Here, she outlines the problematic role that privatisation of services is playing, and highlights a survey which aims to build up a picture of the facts of work in the mental health sector.

As the conference discussions started about how to build support for a Wellbeing Charter I realised that, for some, this is primarily a question of learning how to present the ‘business case’ and learn the creative accounting required to match targets and outputs with actually helping people. As someone who has spent most of their working life as a trade unionist, I would like to suggest that the entire experience of industrial relations is that whatever financial argument you present to protect psychological therapies, actually doing it will require genuine political will on both sides. To simply adopt business school logic just creates a fiction about ‘going forward’.

To make matters worse I was sat next to a rep from an online Cognitive Behavioural Therapy provider talking about how the clinicians they employ value the flexibility of working on a zero-hour contract. It appears she has not connected the growth of ‘flexible work’ with the growing number of people working in mental health services who don’t want to get out of bed in the morning because of the culture of fear they are forced to work in. Online therapy only offers a narcissistic model, where neither the patient nor the clinician ever has to be in contact with another troublesome human being ever again.

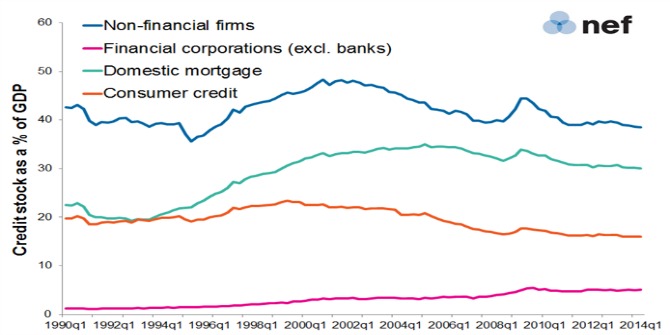

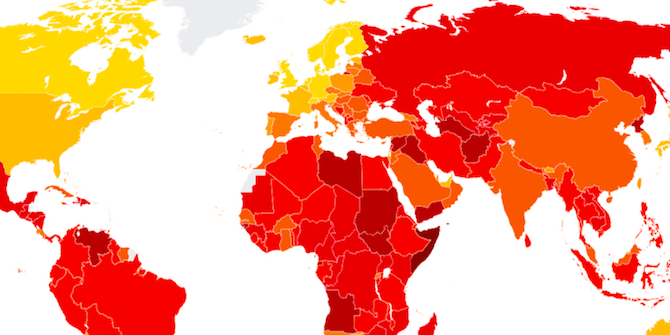

The debate about precarious work is a defining one in the field of employment relations. It links research between nationally set cuts and targets, privatisation of health and social care services and growth of labour outside core-public sector, the use of command and control management, work intensification and bullying cultures. The confusion and ignorance about the employment relations system of mental health workers is very much about the continuous privatisation and restructuring of the NHS and shift of commissioning powers to local level, be that Primary Care Trusts or Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs).

Over the last 5 years there has been a 50 per cent increase in services provided by non-NHS providers with expenditure rising from £6.6 billion to £10 billion. There are an estimated 53,000 private contracts in the NHS with 15,000 within 211 CCGs in community health services and secondary care. An estimated 12.7 per cent of the CCG budget is spent on specialist mental health services – and the primary problems relate to poor contract management and very low penalties for poor delivery. What we do know is that in 2014 half of the private mental health providers commissioned by NHS England to provide specialist care were not fully compliant with NHS standards.

Commissioning Support Units were set up to administer the NHS contracting process and raise any concerns about the governance and monitoring those services provided by private providers. From April 2016, these Units will be privatised (Public Accounts Committee, February 2014). You read that correctly; the administrators in charge of managing third-party contracts will themselves be working for third parties.

Although it’s possible that the third parties currently may offer a good-enough service, if the experience of every other sector is anything to go by, within a two-year period the contracts will be downgraded to compete with ever-stringent budgets. Within 5 years the clinicians and managers in these private companies that came from the public sector will have retired or moved, leaving a new generation of workers without any living memory of good clinical practice or decent work. Given that there is little to no governance of private contractors in the NHS this will happen without even the slightest fuss over patient safety.

In our psychoanalytically-minded society there is a growing split between the established and the disestablished. We see it every day in our services – we now need to allow ourselves to see it in our profession. After four years of talking to mental health workers and now carrying out research into our sector, I think it’s fair to say that we are experiencing a rise in what Sally Weintrobe calls Noah’s-ark-ism. This is the phenomena where those people who still have decent jobs – or who are safely established on pensions or private practice, leadership positions in our professional and training bodies – are protecting what they have while turning a blind eye to those of us who are very-soon-to-be-disestablished.

This second tier of workers includes the Psychological Wellbeing Practitioners who provide the main bulk of IAPT services (Improving Access to Psychological Therapies), the hundreds of honoraries working for free in the NHS, the people manning the mental health call centres, the clinicians carrying out disability welfare assessments and the ones working in social care and support services who were forced to leave their clinical jobs. Our professional bodies are in crisis – torn between defending the sector and their organisation which increasingly cannot happen at the same time. Our unions are literally asleep at the wheel with a growing gap between the rhetoric of collectivisation and the reality of it.

This dis-connect creates a professional culture in psychological therapies much like a 17th Century French Court – a preoccupation with the minutia of court procedures rather than the blood and guts of economic crisis and finding therapeutic modalities that can respond to it. There is a growing possibility that we are within a decade of our profession dying out. As we become de-professionalised, downgraded and demoralised and our experienced leadership retired or retreated into private practice, this leaves the gates open to private providers to fill the gap, and very quickly. It seems that ‘going forward’ leads towards a mental health service made up of tick boxes and compulsory wellness – a ruthless regime of can-do contractors and labour agencies. If this is what going forward looks like I definitely want to go backwards.

This is what we know about as people working in mental health; that all we have is each other, right now, listening and talking long enough to see and understand reality for what it is. A relational model of solidarity where we make the best of the people around us and the bad lot we have been left with in mental health. If you work in mental health – particularly if you work for IAPT, a private contractor, private employment agency or as an honorary – help us build up a picture of the facts of work by taking our anonymous survey here.

Elizabeth Cotton is a Senior Lecturer at Middlesex University Business School. Her academic background is in political philosophy and current writing includes precarious work and employment relations, activism and mental health at work. She is working on her new book, Surviving Work: How to Manage Working in Health and Social Care (Gower 2016). If you would like to contact her anonymously to talk about your experiences of working in health and social care please contact her on info@survivingwork.org or visit www.survivingwork.org.

Elizabeth Cotton is a Senior Lecturer at Middlesex University Business School. Her academic background is in political philosophy and current writing includes precarious work and employment relations, activism and mental health at work. She is working on her new book, Surviving Work: How to Manage Working in Health and Social Care (Gower 2016). If you would like to contact her anonymously to talk about your experiences of working in health and social care please contact her on info@survivingwork.org or visit www.survivingwork.org.

The underlying problem is that the (US lead) diagnostic paradigms – excoriated by the BPS – but sustained by pharmaceutical corporation-led ‘education’ of GPs, who do the bulk of diagnostic, referral and prescribing work, are designed to simplify the effects of the complex biopsychosocial contexts we live in and with, to catch phrases.

The only answer is sweeping restructuring of the content of all mental health-professional education, and retraining of most clinicians (who generally, in my humble 40 years experience as a mental health nurse) never look further than their original training, whether it was 10, 20, or even more, years ago! How can someone steeped in an intellectual system that says “mental illnesses are diseases, like any other” consider their work as ever more than palliative?

Good article but you missed the part about the nurse education altering so that now mental health and indeed what is now called by the appalling euphemism learning difficulties nursing do not get the same amount of input into the specialities as they used to.

With political psychopaths at the helm of our banana republic, ……….. is the current situation NOT to be expected?

I humbly …………….. ask!

I agree. This is reactionary to cuts beyond safe limits. There is a lot of good outcomes that have been missed by this very pessimistic view of partnership working that, although tricky to manage in the way described, places a person focused, bottom up approach that can be less harmful and more effective than to down instructional approaches to mental health recovery. Funding is going backwards. Co produced, resilience and recovery focused practice is very much going forwards.