Over 97 per cent of English local authorities cooperate with one another, providing common public services across separate council areas. Ruth Dixon and Thomas Elston consider how and why this occurs. In a follow-up to their previous post, they find that propensity to collaborate is unpredictable, but partner choice can be partly explained by geographical proximity of councils and similarities in organizational and resource characteristics. Contrary to the view that collaboration is a wholly ‘rational’ strategy chosen simply to improve service costs or quality, therefore, this analysis suggests that both efficiency and legitimacy influenced reform choices.

Over 97 per cent of English local authorities cooperate with one another, providing common public services across separate council areas. Ruth Dixon and Thomas Elston consider how and why this occurs. In a follow-up to their previous post, they find that propensity to collaborate is unpredictable, but partner choice can be partly explained by geographical proximity of councils and similarities in organizational and resource characteristics. Contrary to the view that collaboration is a wholly ‘rational’ strategy chosen simply to improve service costs or quality, therefore, this analysis suggests that both efficiency and legitimacy influenced reform choices.

Historically, English local councils aspired to be self-sufficient. Despite engaging in thorough collaboration with agencies outside of the local government system, local authorities have exhibited a remarkable aversion to the kinds of inter-municipal collaboration commonly practised in Europe and the USA. But this changed markedly after 2010, with the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition government enthusing about shared services and ruling out – temporarily, as it turned out – other types of scale-achieving reforms like the creation of more unitary authorities. ‘I am not at all interested in the structure of local government’ said Eric Pickles while shadow Secretary of State for Local Government, ‘but we will expect councils to … cooperate and work together’. In government, his wish was granted. By 2017 more than 97 per cent of councils participated in at least one inter-council collaboration, providing services such as social care, waste collection, libraries and back-office administration. Our study examined how this significant and ‘un-English’ collaboration was implemented, and what motived such long-resisted reforms.

In our earlier work, we found no evidence of councils attaining the promised financial benefits from sharing back-office or tax collection services across local authority areas. Although savings may have been achieved in particular instances, efficiency did not appear to be a self-evident motivation for shared services (despite this reform being strongly recommended by central government and others as a way to cut costs during the age of austerity). In this follow-up work, therefore, we use social network analysis to investigate other possible drivers of inter-council collaboration, and the characteristics of the resulting networks.

Organizational theory and empirical work on international cases indicate that ‘resource’, ‘organizational’, and ‘political’ considerations may lead to inter-local collaboration and affect partner selection. For example, councils may be motivated to collaborate because of budget constraints or small population size, in order to achieve economies of scale or to share expertise. Conversely, councils that already exhibit a high level of structural complexity may find collaboration less attractive. Choices over partner selection may also be predictable. Do councils favour partners who are most geographically proximate, in order to reduce coordination costs? Or do councils choose collaborators similar to themselves with respect to resources, organizational factors or politics? Partner similarity is often thought to aid the cooperation process; for instance, smoothing the process of reaching decisions and resolving disagreements. On the other hand, councils may seek partners with contrasting experiences and expertise, in order to achieve maximum value from the alliance. To explore these questions, we conducted an exploratory rather than hypothesis-driven study of the English shared services network as it existed in 2017 according to the Local Government Association’s shared services dataset, which we used for this analysis and to prepare Figure 1.

Figure 1: Map of Local Authority shared services partnerships in England in 2017.

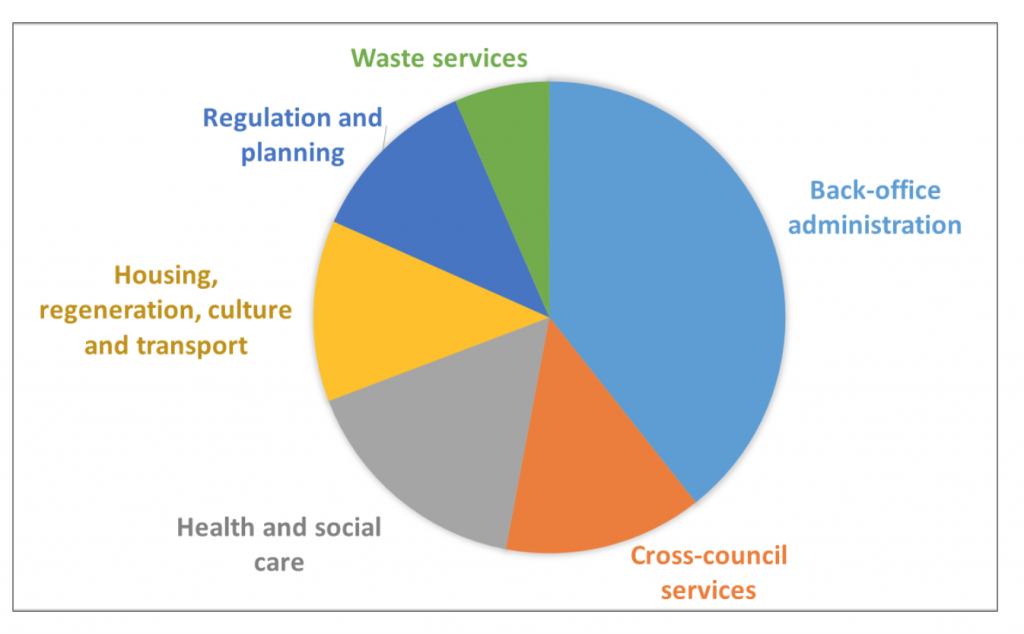

Of the 338 partnerships reported, 182 had frontline (‘programme’) functions, 127 were administrative, and 29 were mixed. Frontline services thus occupy the larger part of the network; although, relative to the volume of administrative support actually performed in councils, back-office work is significantly over-represented. An approximate breakdown of functions is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Approximate breakdown of shared service functions

Propensity to collaborate

Councils belonged to between one and 33 partnerships (median = 3, mean = 4). This number was used as the measure of propensity to collaborate. (This is a count of partnerships rather than activities. Some partnerships cover several council activities, so councils that took part in only a few such partnerships might nonetheless be sharing a significant amount of activity. We did not attempt to assess the level of shared activity represented by each partnership.)

Social network analysis revealed very few significant predictors of propensity to collaborate (less than 5 per cent of the variance was predicted by resource, organizational or political factors, alone or in combination). Among resource considerations, only ethnic diversity (as a measure of social need) showed a weak negative relationship. Given the marketing of shared services as a cost-reduction mechanism, the non-significance of financial health measures is surprising, although may be explained by lack of resources necessary to invest in and manage such innovations. And despite fairly consistent international evidence of inter-local collaboration being used to address diseconomies in small jurisdictions, population does not predict shared services adoption in England. Among the organizational variables, only council type was significantly related to collaboration. Metropolitan districts partnered less than others, despite being legally required to cooperate with one another since the 1980s. Neither opportunities for collaboration within a thirty-mile radius nor internal coordination burden (‘complexity’) predicted collaboration. And, contrary to expectations, political control, partisan alignment with the national government, and electoral stability were not associated with the level of collaboration.

Partner selection

Turning to partner selection, we explored how similar (or different) councils were to their partners using homophily analysis. Homophily occurs when individuals choose partners with similar characteristics; heterophily describes dissimilarity. We found that substantial homophily was demonstrated for organizational variables, with region, geographical proximity, and council type each remaining significant when tested with the others. Intra-regional partnerships (e.g. within the North West) were much more common than expected from proximity alone, even though the nine English regions have largely lost their former coordinating functions. Further analysis found that intra-county relationships were also highly significant. This suggests that sense of local identity, not merely physical convenience, conditioned reform choices.

Resource similarity in 2010-11 (the time when many partnering decisions were made) was associated with partner selection for the variables ethnic diversity, age diversity, external income ratio, and financial reserves, although these variables did not add a great deal of explanatory power to the model containing region, council type and proximity only. When tested alone, councils did seem to partner on the basis of political similarities, as expected. But politics varies greatly between regions. The North East, for instance, had no Conservative councils in 2010, while the South West had no Labour councils. Thus, political homophily disappeared when region was accounted for; indeed, slight heterophily was shown. Given the strong correlation between region and politics, politics may still contribute to the observed regional homophily.

Despite these indications that homophily is important in partner selection, a considerable amount of variance remained unexplained, with no more than 24 per cent of the variance being accounted for by the predictors.

Does partnership activity matter?

Councils may prefer to share services that are less politically salient. We found some support for this in the over-representation of back office services in our dataset. To explore this further, we re-analysed subsets of the whole network containing either front line or back-office services. Very similar associations were found as for the whole network above, with partner selection again being more predictable than propensity to collaborate. (One difference was that front-line partnerships were arranged at markedly shorter distances than back-office administrative partnerships.)

The overall pattern: efficiency–legitimacy trade-offs

Given that we were unable to explain council decisions to collaborate, and yet partner selection did prove more predictable, the question occupying councils since 2010 appears to have been not whether to collaborate, but with whom. So why has inter-local collaboration become a ‘default choice’ among councils after such long-standing resistance?

The pursuit of legitimacy provides an account of public service collaborations that seem to lack the kind of ‘instrumental’, efficiency-related explanations that we tested for. According to institutional theory, organizations strive not only for efficient operations, but also to achieve legitimacy among valued stakeholders, especially when efficiency is hard to attain or difficult to demonstrate. Such legitimacy helps to secure resources from the environment and autonomy from oversight agencies. Separate to the effect of organizational decisions on technical efficiency or goal achievement, the actions of organizations affect external perceptions – whether their behaviour is seen to comply with generally accepted norms and beliefs, for example. This can lead to reform agendas that lack justification from a purely technical point of view, are poorly tailored to individual organizational needs, and do little to enhance, or may even damage, organizational efficiency.

In the case of the reforms in England over the last decade, the unpredictability of the ‘collaborate/don’t collaborate’ decision suggests that councils have adopted the shared services approach regardless of their local circumstances. As Hugh McLaughlin noted, “[t]o argue for the importance of partnerships is like arguing for ‘mother love and apple pie.’ Partnership working has an inherently positive moral feel about it and it has become almost heretical to question its integrity.” Yet despite its fashionable status, collaboration is a perilous strategy, exposing organizations to the risk of conflicting goals, delayed decisions, third-party failures and opportunism. As Huxham and Vangen argued, collaboration is also ‘a seriously resource-consuming activity … only to be considered when the stakes are really worth pursuing.’

Careful selection of collaboration partners is a sensible approach to managing these risks, reducing the chance that pursuit of legitimacy will undermine organizational performance. Homophily among partners reduces the difficulties of securing agreement, for example, while geographical proximity increases trust through familiarity and ease of monitoring. Both were observed in the data, suggesting that councils have engaged in actions to manage the downsides associated with conforming to the collaborative template demanded by the institutional environment.

___________________

Note: The above draws on the authors’ work published in Public Administration. The analysis was funded by the British Academy, the Leverhulme Trust, and the University of Oxford John Fell Fund.

Ruth Dixon is Research Fellow at the Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford.

Ruth Dixon is Research Fellow at the Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford.

Thomas Elston is Associate Professor in Public Administration at the Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford.

Thomas Elston is Associate Professor in Public Administration at the Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Jack Hamilton on Unsplash.

1 Comments