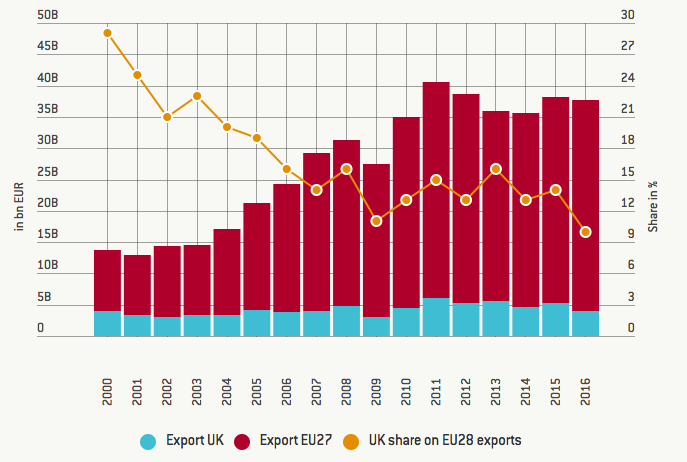

Maria Demertzis and Alexander Roth find that EU-India trade has more than tripled since 2000, but UK-India trade is largely static. The shift is especially noticeable for EU exports to India, where the UK share has dropped from 29% to 10%.

Maria Demertzis and Alexander Roth find that EU-India trade has more than tripled since 2000, but UK-India trade is largely static. The shift is especially noticeable for EU exports to India, where the UK share has dropped from 29% to 10%.

In light of the recent EU-India summit, we revisit the economic relationship between the two partners. Of course, an important component in this relationship is the role of the UK, especially in the context of Brexit.

Figure 1. EU-India trade: Exports

Source: Eurostat. Table compiled by the authors.

Figure 2. EU-India trade: Imports

Source: Eurostat. Table compiled by the authors.

As our numbers show, there has been a steady and substantial increase in EU27 trade (both exports and imports) with India. In fact, EU27-India trade has more than tripled since 2000. Exports from the EU27 to India have increased from €9.8bn to €33.8bn and imports from €10.1bn to €32.0bn.

The UK has not, contrary a common perception, managed to capture much of this increase. In fact, the value of UK exports and imports (at least in euros) has been very stable throughout the whole period. In this respect, the EU27 block has increased in importance for India, whereas the position of the UK has remained the same.

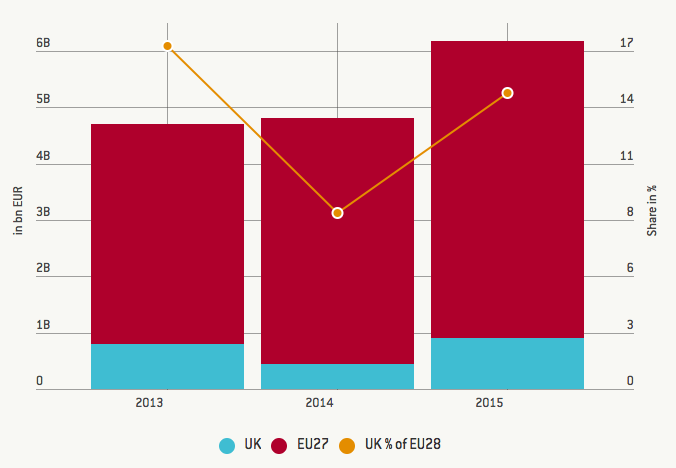

The picture in terms of foreign direct investments is broadly the same: the EU27 is the bigger, and increasingly so, investor in India. The UK invests about one billion Euros per year, while the rest of the EU invests just over 16 billion.

Figure 3. EU’s FDI in India

Source: Eurostat. Table compiled by the authors.

____

Note: This article was originally published on Bruegel.

Maria Demertzis is Deputy Director at Bruegel. She has previously worked at the European Commission and the research department of the Dutch Central Bank. She has also held academic positions at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government in the USA and the University of Strathclyde in the UK, from where she holds a PhD in economics. She has published extensively in international academic journals and contributed regular policy inputs to both the European Commission’s and the Dutch Central Bank’s policy outlets.

Maria Demertzis is Deputy Director at Bruegel. She has previously worked at the European Commission and the research department of the Dutch Central Bank. She has also held academic positions at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government in the USA and the University of Strathclyde in the UK, from where she holds a PhD in economics. She has published extensively in international academic journals and contributed regular policy inputs to both the European Commission’s and the Dutch Central Bank’s policy outlets.

Alexander Roth works as a Research Intern at Bruegel in the area of climate and energy policy. He holds a BSc and MSc in Economics from the University of Mannheim and an MSc from the Free University of Brussels (ULB). Prior to joining Bruegel, Alex worked on the European Carbon Trading System at DG Climate Action in the European Commission. He conducted research at the Centre for European Economic Research (ZEW), Commerzbank AG and the University of Mannheim. Alex’s research interests include empirical microeconomics, focusing on climate, energy, and environmental economics and policies.

Alexander Roth works as a Research Intern at Bruegel in the area of climate and energy policy. He holds a BSc and MSc in Economics from the University of Mannheim and an MSc from the Free University of Brussels (ULB). Prior to joining Bruegel, Alex worked on the European Carbon Trading System at DG Climate Action in the European Commission. He conducted research at the Centre for European Economic Research (ZEW), Commerzbank AG and the University of Mannheim. Alex’s research interests include empirical microeconomics, focusing on climate, energy, and environmental economics and policies.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Hardly surprising as the eu negotiates all the eu deals you can’t do them individually as a sovereign nation within the eu.

Given that the UK has been one of the biggest EU economies with full participation in EU affairs through the whole of the period in question, what logic is there in a claim that the EU has negotiated deals (what deals are we talking about?) to disadvantage the UK?

It looks to me as though UK exporters have simply failed to take advantage of growth in the Indian economy.

But perhaps UK representatives have failed to justify the costs of their participation in external trade?

Very interesting. Is the growth in EU exports not largely down to premium German goods (cars come to mind)? Germany is the best at exports in the whole of Europe so it’s no surprise surely that India is also buying their produce. This does not necessarily tarnish the UK’s hope to increase exports to India – whisky exports could more than treble if tariffs were removed! Huge opportunities…if only people would just get over the idea of a few thousand more Indian students coming to study here…*sigh*.