One of the challenges in higher education policy is to ensure that universities are open to students from all backgrounds and that they don’t simply perpetuate social inequalities. Anne Corbett and Niccolo Durazzi write on the experiences with ‘open’ university systems in countries such as France and Italy. They note that the social inclusiveness of such systems appears to be less than in other European systems, and that admission processes alone are unlikely to be able to correct for this. However ultimately all European universities need to rethink their admission processes and their policies for ensuring students have a chance of success once they begin their studies.

One of the challenges in higher education policy is to ensure that universities are open to students from all backgrounds and that they don’t simply perpetuate social inequalities. Anne Corbett and Niccolo Durazzi write on the experiences with ‘open’ university systems in countries such as France and Italy. They note that the social inclusiveness of such systems appears to be less than in other European systems, and that admission processes alone are unlikely to be able to correct for this. However ultimately all European universities need to rethink their admission processes and their policies for ensuring students have a chance of success once they begin their studies.

This article was originally published on the LSE’s EUROPP blog.

Springtime opens the season for admissions offers and choices in Europe’s selective higher education systems. Some students in the UK will inevitably be disappointed. Their school leaving exam results (GCSE A level in England) won’t be good enough. The recruiting university won’t like their CVs, or maybe, though no institution will admit it, won’t like their postcode either.

But are the waters warmer in other systems of the European Higher Education Area, and particularly in the open systems of Mediterranean Europe, such as Italy and France? There, (roughly) all students who obtain the school leaving, Maturità or Baccalauréat, can enter university. It is a system which has survived the decades since the 1960s revolution which transformed higher education from being an elite to a mass experience.

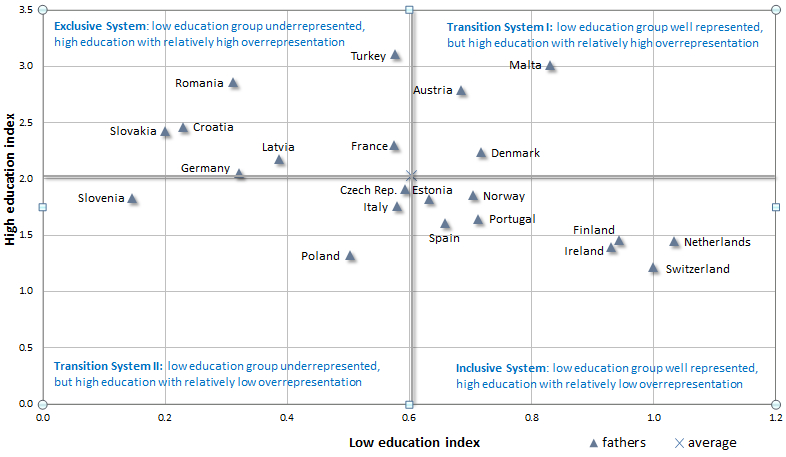

Alas, in many respects the open university systems of Italy and France appear more ‘closed’ than selective systems. The merit-based selection underpinning the system 50 years ago has given way today to some of the highest rates of social selection in European systems. In the Eurostudent survey of 2011 relating the educational status of students’ parents to the student population in university, France finds itself in the bottom quartile of a four-quartile model: an ‘exclusive system, with low education group under-represented and high education group education with relatively high overrepresentation’. Italy is only one quartile above, among the so-called transition systems, with ‘low education group well represented, but high education group with relatively high over-representation’. As the Chart below shows, the only countries which in anyway approach a point of balance are Finland, the Netherlands and Ireland.

Chart: Typology of social inclusiveness in European higher education systems (click to enlarge)

Note: The Chart plots each country based on the percentage of students in higher education whose fathers attained a high education level (vertical axis) and a low education level (horizontal axis). A value of 1.0 indicates that the percentage of students with a highly educated father exactly matches the percentage of highly educated adults in the relevant age group in that country. In other words, any value above 1.0 indicates that students with highly educated fathers (vertical axis) or low educated fathers (horizontal axis) are over-represented in higher education, while a value below 1.0 indicates that students with high/low educated fathers are under-represented. The Chart is then divided into four quarters based on the averages across all countries (the solid lines) to create a typology of different education systems. Source: Chart is reproduced from the Eurostudent IV survey, please see full report for more details.

This sort of data has brought the issue of admissions on to the political agenda of the EU and of the intergovernmental Bologna Process, which is steering the European Higher Education Area in which 47 countries participate. The 2012 Bologna ministerial meeting in Bucharest made it one of its priorities for the next meeting in May 2015 to strengthen policies of widening overall access and raising completion rates. The European Parliament’s Culture and Education Committee has recently received a study on the issue of admissions and its implications, in a comparison of practice in a number of European countries, plus Turkey, the US, Japan and Australia*. Earlier this month, the British agency which monitors access, the Office for Fair Access (OFFA), published a strategy for access and student success in higher education, with recommendations for driving forward change.

This is a measure of how Europe-wide policy preoccupations are being shared, and how the European policy arena of higher education has been enlarged in recent years by political consent. Last time round, which was in 1978, the Commission’s temerity in raising the issue of the diversity of national systems for admission to higher education led to a two year break-down in Council-Commission relations on education matters.

The difference now is that the issue of admissions is no longer primarily a reminder that European higher education systems are culturally diverse, which was the preoccupation in 1978: as such any reform was a challenge to national sovereignty. The issue has now been problematised around questions of equity and quality, which are accepted as legitimate concerns of education at the European level. There is an increasing realisation that the problems of social selectivity in university education in Italy and France are just the tip of an iceberg. No system is immune.

The evidence is overwhelming that social selection is a common problem and that it is both unfair to individuals and against the interests of education systems which are focused on competitiveness and looking for increases in educational attainments. According to Koucky and others, the probability of getting a degree for a student coming from the richest 10 per cent of the population is 90 per cent, from the richest 25 per cent around 75 per cent, and for the poorest 25 per cent of the population, a mere 20 per cent.

Understanding the role of ‘prior’ inequalities: the case of Italy

However, the evidence of trying to correct for inequalities through the admission system alone is not encouraging. The Italian example is instructive. Its admission system is open and it also has specific provisions to ensure some degree of protection for students from disadvantaged backgrounds, such as waiving the application fee.

But in Italy the higher education system continues to reproduce existing socio-economic inequalities. It has been shown that access to higher education in Italy is overwhelmingly shaped by choices made by (or indeed for) students at the tender age of 13/14 – that is to say, well before the admission system comes into play at 17 or 18. This early choice is by far the most significant predictor of whether a student will enrol or not into university.

Nearly every student who attends a gymnasium goes to university. Students from technical and professional schools mostly do not. The choice of high school is in turn, no surprise, significantly correlated with family factors. Pupils from wealthy families tend to go to gymnasia. It is those from disadvantaged backgrounds who fill most of places in the technical and professional schools. Compensatory financial support measures exist, but the (shrinking) set of scholarships cover only (approximately) 60 per cent of eligible applicants in Italy, and the grants are insufficient to cover living costs.

Two policy directions traditionally debated in selective systems (e.g. in England) appear to have recently gained importance in open systems as well. The idea of grants and well-designed student loans that cover the cost of higher education (in terms of both course fees and costs of living) advocated by Nicholas Barr and others is one example. Another example lies in addressing the problem of under representation in higher education by tackling it as an in issue of inequality prior to the formal processes of access and admission to higher education.

The under-represented groups are known to be the least likely to even consider enrolling for higher education. Increasingly we are seeing the problem approached as a life cycle issue with strategies to intervene early in the education process, even from early childhood (an approach also supported by the recent OFFA report). The aim is to tailor policy intervention to better supporting the individual pupil through early childhood development strategies and the improvement of primary and secondary educational outcomes.

Why admission systems should also be concerned with output data

But some of the problems most starkly exemplified in open systems are also being problematised as a systemic aspect of admissions. The fact that students from poorer backgrounds are not only less likely to accede to university, but also more likely to drop-out, may be due in part to the lack of appropriate ex-ante information in the admission process. Hence, the aim of increasing graduation rates is an issue for higher education systems on efficiency and quality grounds, as well as a matter of equity.

Providing better ex-ante data for potential students is an idea of the moment. As Barr shows, individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds tend to have access to less and lower quality information. This approach is being criticised as a burden on all those involved and hence defeating its purpose. Yet, seeing this lower probability of graduation for students from disadvantaged backgrounds as the outcome of throughput processes, as well as input processes, highlights the need for a mechanism which matches applicants with the degree programme that maximises their chances of graduation.

In Italy there are currently efforts being made to provide accurate ex-ante information to students to help them assess their own suitability for a specific degree and, hence, their likelihood of successful completion and graduation. This points to the expanded role which admissions systems can play as a mechanism not only for entry, but also for completion by predicting the probabilities of a student’s future academic success (also an OFFA strategy). The Italian experience of using non-selective orientation entry tests to provide students with an ex-ante assessment of their preparation for a specific course appears to have had a positive impact on reducing drop-out rates.

Policy implications

Open admission systems to higher education may have been attracting political attention because of the paradox coming to light that ‘open’ may not mean equitable. But the current spate of policy proposals suggests that the focus on Italy and other open systems has been effective in revealing the iceberg underneath. Students from at risk groups not only have the right to access higher education; the system should do what it can to ensure that the experience of higher education should be crowned with success.

This is an opportunity for European institutions to show that they are well placed to pick up the baton. There are two dates in prospect on the policy calendar. The European Parliament’s Culture and Education Committee will be deciding before the summer whether and how it will respond to a report on these very issues. Next year it will be the Bologna ministers’ turn. Might the iceberg be starting to melt?

* The study is titled Higher Education Entrance Qualification and Exams in Europe: A Comparison (ref: IP/B/CULT/IC/2013-007) and it has been jointly implemented by LSE Enterprise and RAND Europe. The authors of this article participated in the study and gratefully acknowledge the European Parliament for allowing the use of some of the material from the study to write this article.

Note: This article gives the views of the interviewee, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Anne Corbett – LSE

Anne Corbett – LSE

Dr Anne Corbett is a former Visiting Fellow in the European Institute of the London School of Economics and Political Science. She is the author of Universities and the Europe of Knowledge: Ideas, Institutions and Policy Entrepreneurship in European Union Higher Education, 1955-2005, Basingstoke, Palgrave (2005) and a former journalist.

Niccolo Durazzi – LSE

Niccolo Durazzi – LSE

Niccolo Durazzi is Deputy Director of LSE Consulting at LSE Enterprise. He has worked on several projects on education and social policy for European institutions, including DG Education and Culture of the European Commission, European Parliament, European Training Foundation and Eurofound.