What affects public support for electoral reform? Abigail Heller argues that experience with an electoral system similar to that under consideration affects public opinion by reducing uncertainty about the likely effects of reform, thus affecting support for change. Such experience is particularly important in the absence of strong party cues, as was the case with Labour during the 2011 Alternative Vote referendum.

What affects public support for electoral reform? Abigail Heller argues that experience with an electoral system similar to that under consideration affects public opinion by reducing uncertainty about the likely effects of reform, thus affecting support for change. Such experience is particularly important in the absence of strong party cues, as was the case with Labour during the 2011 Alternative Vote referendum.

In 2011, when the public voted to keep the first-past-the-post electoral system in the alternative vote (AV) referendum, there was an effort to understand why citizens voted the way they did. One factor that scholars paid particular attention to was cues from party leaders (i.e., voters basing their choice on the stated position of their party) or other elites. But the Labour Party was divided over AV — despite being the only party to advocate for an AV referendum in their 2010 manifesto, their MPs split and campaigned on both sides (with the Labour leader, Ed Miliband, campaigning in favour of AV). Internationally, there are other cases where parties decline to take a position on electoral reform or where parties are divided. In such cases, how do citizens determine whether to support electoral reform? Even if voters prefer rules that help their preferred party, how do they know which rules will be beneficial if their party is giving them weak or confusing cues?

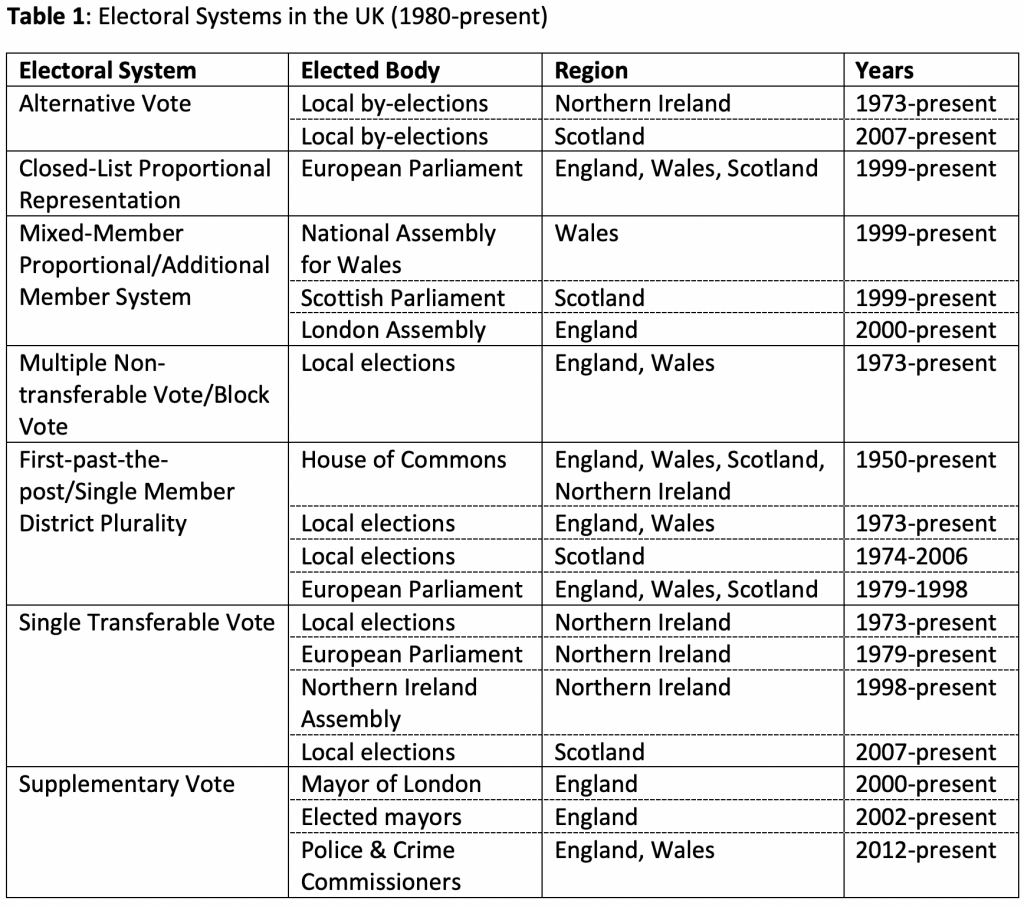

In a recently published paper, I argue that voters can use their experience with different electoral rules at other levels of government to understand the likely effect of the proposed rules on their preferred political party and thus whether to support electoral reform. In the UK, seven electoral systems are used for selecting members of local, regional, national, and supranational bodies (see Table 1). Therefore, depending on where in the UK one lives, one may be exposed to some of these different systems. This type of experience with multiple systems is common in other parts of the world as well, but it’s effect on support for electoral reform has not been studied. For example, Australia, Canada, Chile, France, Nepal, and the United States all use different rules for elections to different bodies, while places like Italy, Japan, and New Zealand have used different rules for elections to the same body over time.

Note: Please see the paper for additional details, how these systems were coded, and sources.

How does experience with different rules affect support for electoral reform? I argue that experience with an electoral system similar to that being proposed provides information about how party fortunes and policy outcomes are likely to be affected. This information can either increase or decrease support for reform, depending on the type of experience — positive or negative. Because people prefer electoral rules that benefit their preferred party, a positive experience with a different electoral system (in which one’s party wins a greater proportion of seats than at the most recent House of Commons election) may increase support for reform, while a negative experience (in which one’s party wins a lower proportion of seats than in the House of Commons) may decrease support for reform. However, I argue that this experience is particularly important for those who do not receive clear, consistent cues from their party. In other words, in the UK, experience with alternative electoral systems is most important for Labour supporters.

To test this theory, I use data from the British Social Attitudes survey which allows me to track support for the introduction of proportional representation (PR) for House of Commons elections from 1986 to 2015. I test the effect of the introduction of (i.e., experience with) Mixed Member Proportional (MMP; also known as the Additional Member System) in Scotland and Wales on support for electoral reform at the national level. This test, which uses a difference-in-differences design, can uncover the effect of experience with MMP by comparing the change in support for reform before and after 1999 (when MMP was introduced for Scottish Parliament and National Assembly for Wales elections) within Scotland and Wales to the change in support for reform before and after 1999 in Northern England and the Midlands (where people were not exposed to MMP).

Because the type of experience (positive or negative) is dependent on how one’s preferred party performs, I run the analysis by grouping supporters of the Labour Party, supporters of the Conservatives, and supporters of other parties (there are several other parties represented in the data, but the largest by far are the Liberal Democrats, the Scottish National Party, Plaid Cymru, and the Green Party). The theory predicts that experience with MMP should make Labour supporters in Scotland and Wales less likely to support electoral reform for the House of Commons because Labour tended to win a lower proportion of seats in the Scottish Parliament and National Assembly for Wales than they did in House of Commons elections during this time. Additionally, Labour supporters don’t receive clear cues from their party about electoral reform, which is why experience should have a statistically significant effect. In contrast, because the Conservatives and other parties give more consistent and explicit cues about electoral reform, their supporters should be less likely to rely on experience and MMP is not expected to have an effect for supporters of these parties.

I find that, consistent with the theory, experience with MMP causes Labour supporters in Scotland and Wales to be less likely to support electoral reform for the House of Commons than their peers in Northern England and the Midlands. Moreover, experience with MMP does not have an effect for supporters of the Conservatives or other parties since these parties gave more explicit cues during this time, meaning that their supporters were less likely to rely on experience to determine their support for reform.

This study implies that experience with alternative electoral systems can affect support for reform and is most important for those who don’t receive strong cues from their party. But while I explored the effect of one type of electoral system experience (experience with MMP), there are other factors that influence support for electoral reform including party cues or preferences regarding the fairness of the electoral rules. More work is needed to understand how these factors interact. Nevertheless, this project is an important step towards a better understanding of public opinion about electoral rules, which is critical as countries increasingly use referenda to determine electoral rules.

_______________________

Note: the above draws on the author’s published work in Electoral Studies.

Abigail Heller earned a Ph.D. in Political Science from Emory University in 2021, and was the 2020-2021 Research and Engagement Graduate Fellow with the Emory Libraries and Emory Center for Digital Scholarship.

Abigail Heller earned a Ph.D. in Political Science from Emory University in 2021, and was the 2020-2021 Research and Engagement Graduate Fellow with the Emory Libraries and Emory Center for Digital Scholarship.

Photo by stefan moertl on Unsplash.