Javier Rivas and James Rockey explain how voters’ desire to boo for candidates they dislike, rather than cheer for candidates they do like, has been increasingly important at recent elections. They also find that the importance of booing is greater amongst the least well-off voters, which helps explain the success of extremist ideas in the UK and Europe since the 2008 financial crisis.

Javier Rivas and James Rockey explain how voters’ desire to boo for candidates they dislike, rather than cheer for candidates they do like, has been increasingly important at recent elections. They also find that the importance of booing is greater amongst the least well-off voters, which helps explain the success of extremist ideas in the UK and Europe since the 2008 financial crisis.

Why do voters bother to vote? The so-called paradox of voting holds that, in elections that are not expected to be close, it makes little sense for voters to spend the time and effort voting given they have little chance of altering the outcome. One explanation is that voting is an opportunity for citizens to express who they want to be in office, and that doing so is enough reward in and of itself. In the standard version of this story, by voting for a candidate or party, the voter is stating who she prefers out of the set of candidates.

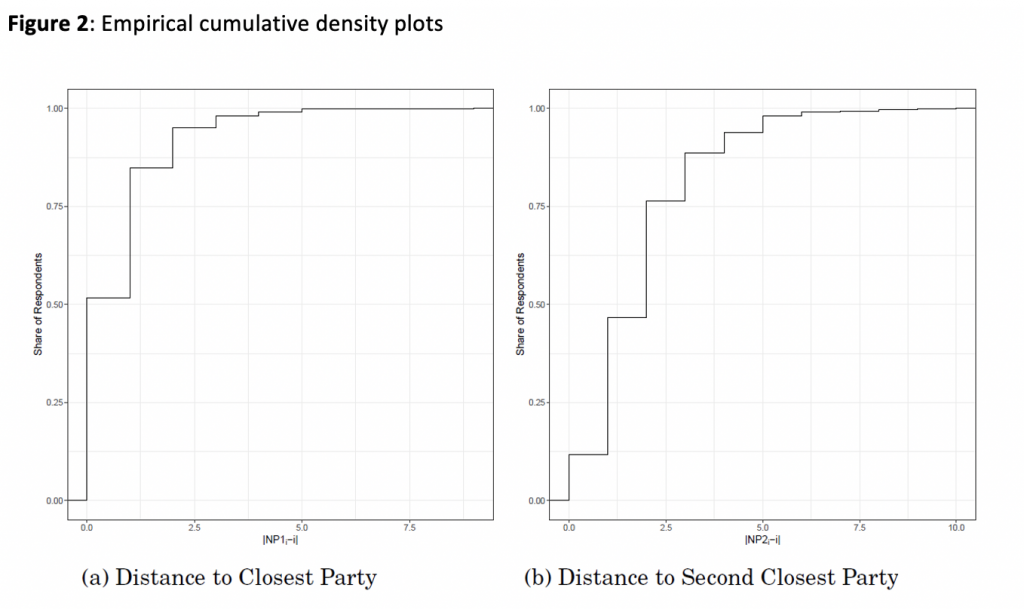

Recently, this idea has been extended to a much richer view that voters use elections to express more than just their top choice. Rather than voting being viewed as solely the act of cheering for the most preferred candidate, it can also be seen as the act of booing for a candidate the voter dislikes. That is, a voter’s behaviour in an election may be driven by the desire to express dislike rather than like. In practice, this means that even if there is no candidate a voter likes sufficiently to make it worthwhile to go and vote for, they may nevertheless cast a vote because of a strong dislike for another candidate. We argued that cheering is more likely when there is a candidate or party who matches a voter’s politics, and booing is more likely to be a reason to vote the further away other parties are. Thus, at the last UK General Election, voters may have been motivated by their dislike of Johnson or Corbyn rather than their liking for the alternative.

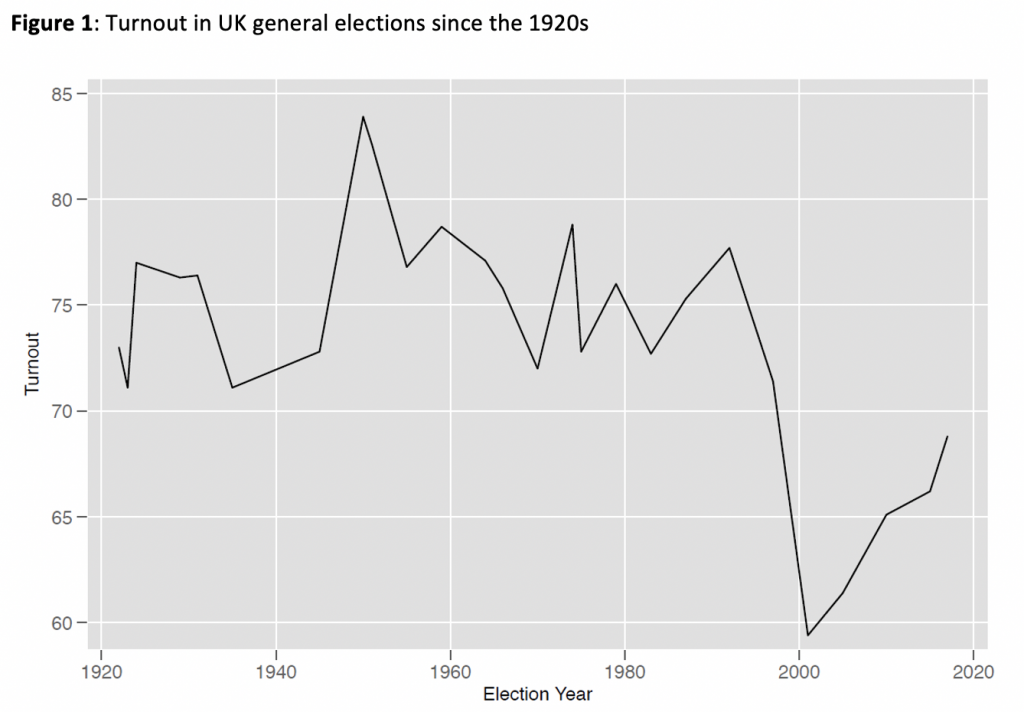

In our research we took this idea further and explored just how much booing mattered compared to cheering in UK general elections and how this has changed over time. We analysed data from the British Election Study (BES) and documented three distinct facts about booing. First, we found that booing is indeed an important factor affecting elections with a significant influence on turnout. Second, we observed that the importance of booing relative to cheering has increased in recent elections, especially since the late nineties. Third, we detected a relationship between how much booing manifested for a voter and whether or not such voter came from a deprived area. We found that the effect of booing is more pronounced for voters who come from more deprived areas.

How much does booing matter? Our estimates suggest that if a voter’s second most preferred party is one point further away on a 10-point ideological scale, then this increases the probability of their voting by 2-3%. This is a significant figure, even more so if one considers that turnout in the last decade has not risen above 70%.

To the extent that booing matters, other things being equal elections in which parties have similar platforms will have a lower turnout. Thus, the increase in turnout in the UK and some European countries in the last decade can be linked to the increase in party polarisation in these countries. Similarly, booing may have been a contributing factor to the creation of new parties with ideologies closer to the extremes of the political spectrum.

How booing matters compared to cheering? We estimate that the most preferred party by the voter being one point further away on a 10-point ideology scale can decrease the probability of turnout by up to 2% (the cheering effect). Therefore, not only is the booing effect important, it is perhaps even more so than the cheering effect. More striking is the fact that when looked at over time, the relative importance of booing has nearly quadrupled since the late 1990s according to some of our estimates.

Although the causality is unclear, this increasing desire to boo may explain again why party polarisation has increased; it is no longer the case that having a political platform close to the median voter maximises votes, rather having a distinct ideology that minimises boing could attract more votes. Similarly, the increase in booing and decrease in cheering is what may have contributed to the decrease in party identification over these years. According to previous research, the percentage of voters not identifying with any party went from below 5% in 1964 to over 20% by 2015, while the share identifying strongly or very strongly with a party went from 85% in 1964 to 57% in 2015.

Finally, our third finding suggest that if we order voters by their deprivation score – from 1, most deprived, to 5, least deprived – we see that booing is most important for the most deprived, less important for those in quintiles 2 and 3, and unimportant for quintiles 4 and 5. The fact that the importance of booing is greatest amongst the least well-off voters, alongside its increase in recent years, suggests that the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent austerity may have been a catalyst for the increased importance of booing. In the same way that support for Brexit was higher in areas most affected by austerity, the declining fortunes of the least well-off may also have contributed to a dislike for the political class and a desire to punish rather than reward, affecting all parties and rewarding the extremes.

In summary, we found evidence that the desire of voters to boo parties they dislike has become an important predictor of turnout in recent years. This implies reductions in turnout in support of parties who are similar to their competitors and increased support for more extreme parties. As such, it can help understand recent increases in political polarisation, populism, and extremist parties.

_____________________

Note: the above draws on the authors’ published work in the Journal of European Political Economy.

Javier Rivas is Senior Lecturer in Economics at the University of Bath.

Javier Rivas is Senior Lecturer in Economics at the University of Bath.

James Rockey is Associate Professor at the University of Birmingham.

James Rockey is Associate Professor at the University of Birmingham.

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash.