Daniel Fitzpatrick and Dave Richards examine the patterns of gender representation in the UK Civil Service under the coalition government. They explain why there was a regressive change in the most senior grades and highlight the role of ‘critical feminist actors’ in driving forward gender equality and diversity agendas in Whitehall.

Daniel Fitzpatrick and Dave Richards examine the patterns of gender representation in the UK Civil Service under the coalition government. They explain why there was a regressive change in the most senior grades and highlight the role of ‘critical feminist actors’ in driving forward gender equality and diversity agendas in Whitehall.

The equal representation of women and men in positions of political power continues to prove elusive. Institutions – including political parties, business, and the media – are criticised for the slow, incremental nature of change. Progress towards the goal of gender parity seems to move at a snail’s pace. But what happens when gender parity is achieved? This is a question we explore in a new article for British Politics examining the patterns of gender representation in the UK Civil Service under the coalition government (2010–2015). In it, we interrogate the claim that there was a regressive change in the proportion of women in the most senior grades of Whitehall during this period.

2011 can be identified as a notable date in which gender parity in the most senior grade of permanent secretary in Whitehall was attained for the first time. It represented a hugely symbolic moment, emboldening the then Cabinet Secretary, Gus O’Donnell to declare that the Civil Service had become a ‘genuinely meritocratic’ organisation.

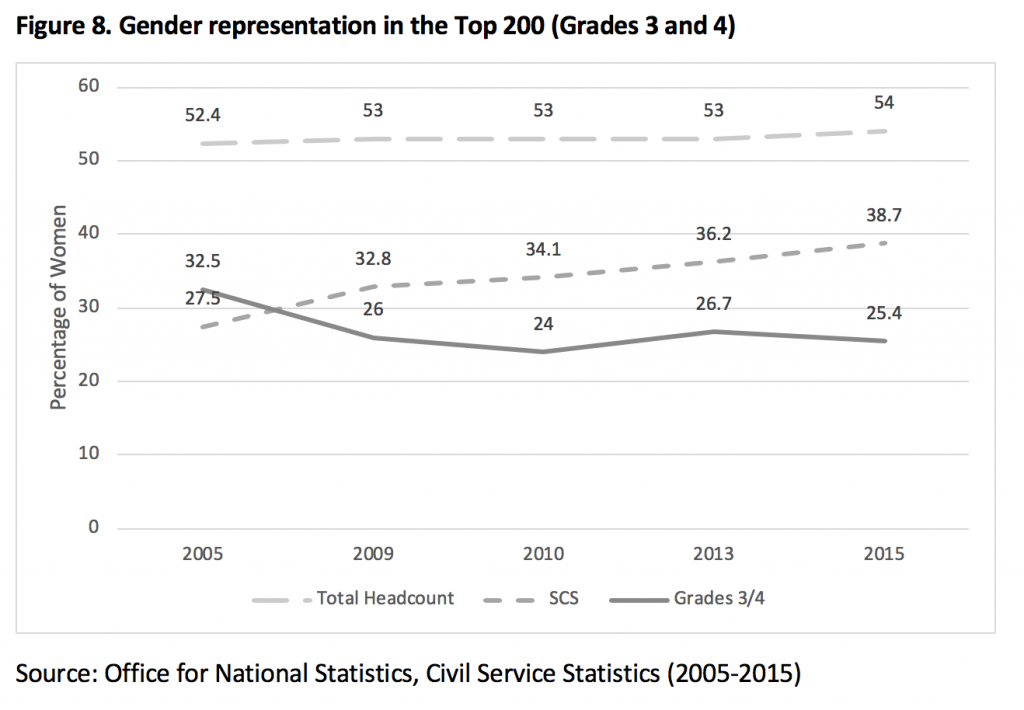

Fast-forward to the end of the Coalition and the claim that meritocracy—free of bias (conscious or otherwise)—as the new norm appeared somewhat premature. The headline figure showed that women accounted for more than half of all UK civil servants (at 53.5%). Yet, a more nuanced examination revealed that the most senior policy roles in Whitehall remained predominantly the preserve of white, middle-class men, with only 38.7% of women working in the top four pay bands. At the highest grade of permanent secretary, the earlier gender parity achieved in 2011 had vanished by 2013, with only four of the 16 permanent secretaries being women, rising to six by that Government’s end.

These shifts in the make-up of Whitehall drew accusations that the gender diversity agenda under the Coalition had at best been de-prioritised. A National Audit Office report concluded that ‘momentum was lost’. Labour’s Deputy Leader Tom Watson regarded it as ‘shameful’, while the Shadow Cabinet Office Minister Louise Haigh argued: ‘The top brass of the civil service is now more white and more male than at any time in almost two decades and the glass ceiling which was smashed in 2011 when women achieved parity has now been painstakingly reassembled and reinforced’. O’Donnell’s successor, the now sadly departed Jeremy Heywood recognised the figures were ‘disappointing’ and that they did ‘not represent the gender diversity we are determined to achieve’. It prompts an important question: was Gus O’Donnell somewhat presumptuous to claim in 2011 that Whitehall had become both an exemplar employer and a meritocratic organisation?

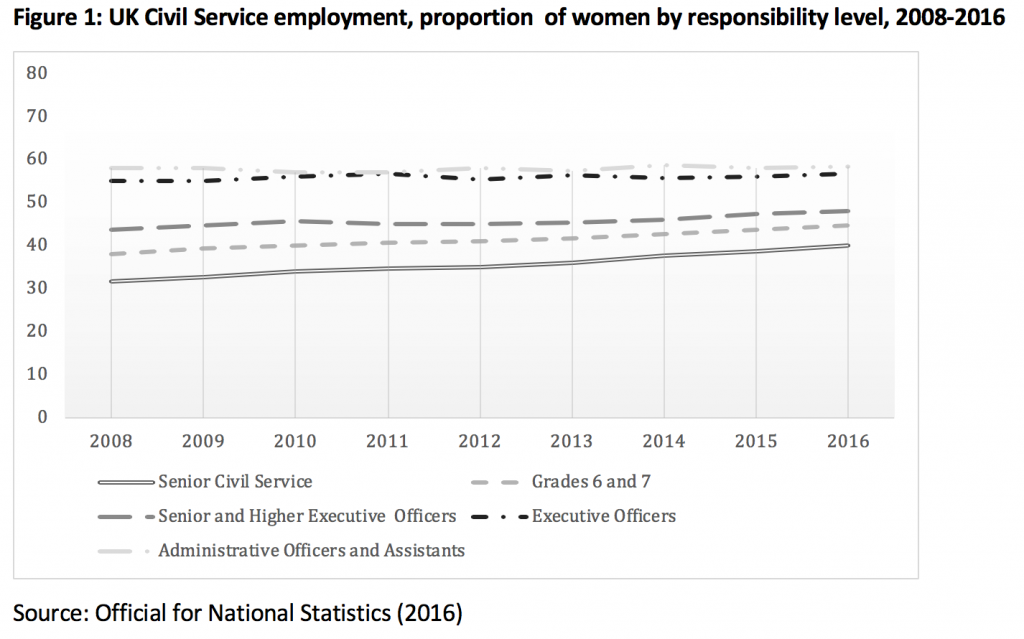

What is most notable under the Coalition is the gendered dimension to recruitment at the most senior levels. Women make up more than half of the civil service. For the senior civil service in 2015, the figure was 38.7%, rising above the putative ‘tipping point’ of 40% in 2016. Yet, despite this, the qualitative evidence suggests the culture and practices of the senior civil service were far from being ‘feminised’.

A series of high-profile, ‘early’ departures saw several female Permanent Secretaries (including Helen Ghosh, Moira Wallace and Gillian Morgan from their respective leadership of the Home Office, Department of Energy and Climate Change and the Welsh Government) being replaced by men. This reinforced the perception that the appointment of women at the highest grades remained an issue.

The Coalition’s perceived ‘problem with women’ was attested by two separate reports from the Hay Group and the National Audit Office which concluded that macho, exclusionary cultures were more prevalent within the upper echelons of Whitehall compared with the rest of the civil service, leading to women ‘choosing to opt out of more senior roles’.

Beyond Critical Mass

What the aggregate data on the Coalition years reveals is an increase in the proportion of women in all grades of the civil service, except the Top 200 group. The contrast in these two sets of figures raises questions over established ‘critical mass’ approaches. The traditional argument suggests that once critical mass is reached, the previously under-represented group becomes more ‘socially prominent’ in the organisation. The point at which critical mass of women in an organisation is reached is portrayed as a step-change for its culture and working practices. Research by Kanter (1977), for example, argues that women must account for at least 40% of an organisation, if there is likely to be any impact upon institutional culture, norms and values.

Our research supports previous empirical studies that question an assumed relationship between ‘sheer’ numbers of women and discernible changes in outcomes and organisational cultures. Part of the explanation points to the absence of a critical mass of women at the top—permanent secretary and director-general level—with the evidence above revealing it flat-lined to around 25% during the Coalition period.

Bringing in the role of the critical feminist actor

In Westminster-style democracies, power and resources tend to be concentrated within a small group of actors. There is a need to focus on the currently under-explored role played by departments and more specifically senior civil servants, as critical feminist actors. Those officials operating within the Top 200 have considerable discretion over the direction of their departments and also have significant managerial autonomy to represent women actively within and across the civil service.

The lack of salience attached to gender diversity in Whitehall by the Coalition highlights the precarious nature of ‘gender mainstreaming’: the ‘embedding of gender equality in systems, processes, policies and institutions’. Our approach here follows those who argue that the policy machinery of gender mainstreaming is ‘weakly institutionalised and easily dismantled when the political landscape changes’. Individual actors—operating alone or more likely in collaboration with others—are required to do the ‘institutional work’ not only in the creation, but also the maintenance, of equality and diversity practices and outcomes.

What this suggests is that in striving to achieve gender diversity, we must also pay heed to the relational role that individuals and structures play in maintaining as well as reaching important milestones in representative bureaucracy, so that these are not merely symbolic victories.

_____________

Note: the above draws on the authors’ published work in British Politics.

Daniel Fitzpatrick is a Lecturer in Politics and International Relations at Aston University.

Daniel Fitzpatrick is a Lecturer in Politics and International Relations at Aston University.

Dave Richards is Professor of Public Policy and Head of Department at the University of Manchester.

Dave Richards is Professor of Public Policy and Head of Department at the University of Manchester.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain).