Technology is widely considered the main source of economic progress, but it has generated cultural anxiety throughout history. Here, Joel Mokyr, Chris Vickers and Nicolas Ziebarth place today’s angst about technological change in a historical context. They emphasize that today’s worries are not new to the modern era and that understanding the history provides perspective on whether this time is truly different.

In a recent paper, we place today’s angst about technological change in a historical context. In particular, we study three prominent concerns: (1) Will technological progress cause a substitution of machines for labour and lead to widespread unemployment; (2) Will technology lead to a dehumanisation of work; and (3) Are the days of strong economic growth behind us? We first look at how accurate the predictions of contemporary economists were on these issues, and then what lessons their successes and failures have for today’s prognosticators.

Economists during the Industrial Revolution were divided over whether technological progress would lead to lower employment. Most distinguished between short-term dislocations and longer term, chronic unemployment. Even optimists such as John Stuart Mill and David Ricardo conceded the possibility of short-term unemployment, while others such as Thomas Mortimer believed machines could remove the men from the labour force more permanently. Given the hand wringing over the possibility of technological unemployment, one might have expected it to be a serious problem in the economy of the day, yet there is scant evidence of widespread, long-term idle labour. Indeed, the complaints were rather about rapidly expanding factories and long hours and child labour. Where the case for historical pessimism is stronger is in wages rather than unemployment per se. By some accounts, living standards failed to rise until the middle of the 19th century, decades after the beginning of the Industrial Revolution.

After largely disappearing in the late 19th century, the Great Depression brought a revival of concerns about “surplus” labour, worries which similarly disappeared after the return of economic growth. While the fretting of some contemporary economists about widespread idleness were largely wrong, the costs borne by displaced people were real and far from negligible, with wages for laborers by many estimates taking more than a working lifetime to have risen to reflect rising productivity.

The second source of angst we address is the alleged dehumanisation of work brought on by technological progress. Even Adam Smith, while extolling the efficiency of the division of labour, worried about the deleterious effects of simple, repetitive work. Factory discipline came to replace a more informal, and arguably more flexible method of labour organisation of independent artisans, and much of the factory work itself was dangerous and gruesome. What is striking about these arguments is the degree to which many of them are the inverse of modern anxieties. While today’s pessimists decry the uncertainty associated with the gig economy, the move from independent artisans to factories and a routinised workday was traumatic in its own way. Workers were dissatisfied by the highly structured and regimented nature of factory work and the imposition of discipline through fines and penalties. We see little reason to doubt that workers can adjust to workforce patterns that arguably mirror pre-industrial ones.

Finally, a number of modern writers such as Tyler Cowen or Robert Gordon have suggested something of the reverse view, asserting that the days of rapid technological progress are behind us. This worry, too, is nothing new historically. John Stuart Mill wrote about a “stationary state” during the Industrial Revolution. The Great Depression saw an outbreak of similar pessimism. One notable exception is John Maynard Keynes, whose famous essay “Economic Possibilities of our Grandchildren” predicted that by 2030, our most pressing problem would be how to occupy our leisure time after a century of economic growth.

The overarching point we would emphasize is that today’s worries are not new to the modern era and that understanding the history provides perspective on whether this time is truly different. We are skeptical about the more extreme of modern anxieties about long-term, ineradicable technological unemployment or a widespread lack of meaning because of changes in work patterns. Predictions about unemployment are often based on looking at only process innovation, missing the more important long-term trends in the invention of entirely new products, and the jobs that come with these. While making specific predictions about the future of technology is imprudent, we are sceptical about an end to major innovation any time soon, particularly with scientists and researchers having access to increasingly powerful tools and sources of data to build on previous discoveries.

We emphasize that the transition paths to the economy of the future may be quite painful for some industries and workers, as these transitions tend to be. One difference from earlier transitions, particularly the Industrial Revolution, is that, much more than in the past, public policy may be used to ameliorate the harsher effects of dislocation in welfare states. Direct income redistribution could supplement the income of some classes of workers. A complementary strategy would be to increase the set of publicly provided goods. However, we should not let these real worries about dislocations unduly distract us from the overarching lessons of the least two centuries of history, which were ones of technologically driven rising living standards and largely failed predictions of eminent calamity.

___

Notes: this post originally appeared on LSE Business Review and is based on the paper The History of Technological Anxiety and the Future of Economic Growth: Is This Time Different?, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Volume 29, Number 3 — Summer 2015 — Pages 31–50.

About the Authors

Joel Mokyr is Robert H. Strotz Professor of Arts and Sciences and Professor of Economics and History, Northwestern University since 1974. He is also Sackler Professorial Fellow, Eitan Berglas School of Economics, University of Tel Aviv.

Joel Mokyr is Robert H. Strotz Professor of Arts and Sciences and Professor of Economics and History, Northwestern University since 1974. He is also Sackler Professorial Fellow, Eitan Berglas School of Economics, University of Tel Aviv.

Chris Vickers is Assistant Professor of Economics at Auburn University, Alabama. He joined the department in 2013 after finishing his Ph.D. at Northwestern University. Dr. Vickers’ research interests are in economic history and applied microeconomics.

Chris Vickers is Assistant Professor of Economics at Auburn University, Alabama. He joined the department in 2013 after finishing his Ph.D. at Northwestern University. Dr. Vickers’ research interests are in economic history and applied microeconomics.

Nicolas Ziebarth is an Assistant Professor in the Tippie College of Business at the University of Iowa. He obtained his PhD in Economics from Northwestern University. Dr Ziebarth was a finalist for the Economic History Association’s Nevins Prize in 2012, received a Sokoloff Graduate Fellowship in 2011 and a Robert Eisner Memorial Fellowship, Northwestern University, in 2011.

Nicolas Ziebarth is an Assistant Professor in the Tippie College of Business at the University of Iowa. He obtained his PhD in Economics from Northwestern University. Dr Ziebarth was a finalist for the Economic History Association’s Nevins Prize in 2012, received a Sokoloff Graduate Fellowship in 2011 and a Robert Eisner Memorial Fellowship, Northwestern University, in 2011.

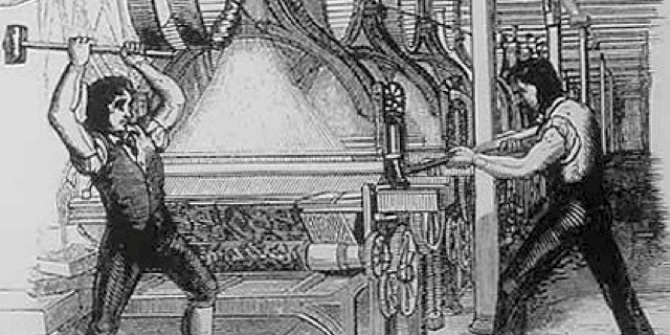

Featured image credit: Luddites Later interpretation of machine breaking (1812) – Public Domain

The lesson from the past that sticks out for me is the Black Death:in the aftermath of which there was a severe shortage of ‘labour’.

As things stand today the old habits of exploitation and abandonment are still to the fore. The consumers within a particular economy are not readily supported by tax collection or tax spend;this would have to change. While DID sounds good, and could offset the worst. What would a State threaten its population with, if there were to be no hardships?

Which brings us back to ‘natures’ population correctives (The Black Death) and our old friend War.

The historical record can certainly inform us, but sometimes a new development is so fundamental that it calls into question the value of such extrapolations. This is such a time.

Machines are increasingly able to learn the same way that people learn: by observation, trial, error, and correction. While nascent, this competency is rapidly expanding in both scope and subtlety. When a machine can reliably perform some economic function at least as well as a person, cost/benefit analysis will eventually favor the machine.

For example, IBM’s Watson Division is now partnering with hundreds of companies to deploy the Watson AI. Each such partnership targets an area of work presently performed by people. While IBM carefully positions this as “helping” people, in reality they will only be helping those who remain after the layoffs. Barring a sudden increase in demand for such services, the layoffs are certain. It needn’t replace an entire profession. For, example, the 20% of legal professionals’ hours spent on research are now in Watson’s crosshairs, as are forms of medical diagnosis.

Ever more activities formerly regarded as “uniquely human creativity” are being automated. AI’s have made major scientific discoveries, created inventions that have been awarded patents, composed new music in the style of masters, and now regularly write articles published in major media. No profession can be complacent about its future.

We need to start preparing for a future in which many of today’s professionals and most of our manual laborers are unemployed and unemployable. This time is rapidly approaching, as the progress of machine intelligence, sensors and robotics are accelerating along the path of Kurzweil’s Law, which will continue to drive progress long after Moore’s Law reaches its limit.

Viable solutions that offer us a basis for sustainable universal abundance are at hand. I propose one candidate in my recent book, A Celebration Society.