The Lib Dems face the “unity-distinctiveness dilemma”: they must defend the overall coalition record whilst also emphasising distinct achievements. In a recent paper based on international case studies, Akash Paun & Robyn Munro set out five lessons for the Lib Dems as the party seeks to avoid electoral collapse in May 2015.

The Lib Dems face the “unity-distinctiveness dilemma”: they must defend the overall coalition record whilst also emphasising distinct achievements. In a recent paper based on international case studies, Akash Paun & Robyn Munro set out five lessons for the Lib Dems as the party seeks to avoid electoral collapse in May 2015.

As the UK coalition government heads towards its endgame, the two parties of government face a novel set of challenges in governing together while positioning themselves for the next election. As the smaller partner, the Liberal Democrats face a particularly tough situation. The party must emphasise its distinct values and achievements, while defending – or at least not disowning – the overall coalition record, including the many major policy initiatives such as NHS and welfare reform that have been Conservative-led. In the academic literature on coalition government, this tension faced by parties in coalition government has been termed the “unity-distinctiveness dilemma”, defined as the need “to maximise governmental effectiveness while at the same time protecting the identity and distinctiveness of the parties involved (and hence their electoral viability)”.

This dilemma becomes particularly acute in the latter stages of coalition, when the political need to differentiate reaches its peak, while pressures on coalition unity threaten to bring the government crashing down before the end of its term. To inform debate about how the UK coalition parties should approach the final straight of coalition, the Institute for Government conducted research into six coalitions from other political systems. Our focus was how smaller parties fare when sharing power with larger partners – a position one previous study succinctly described as akin to being “punchbags for heavyweights”. Based on our international case studies we set out five lessons for the UK Liberal Democrats as the party seeks to avoid electoral collapse in May 2015.

Four of the six smaller parties we looked at – New Zealand First (NZF), the German FDP, the Dutch Democrats 66 (D66) and the Irish Greens – suffered a significant loss of support during their time in office (see Figure 1). New Zealand First (from 1996-99) and the Irish Greens (from 2007-11) saw their support collapse over only a single term of office, in both cases the only experience either party has had of government. D66 spent virtually the entire 1994-2006 period in government (only returning to opposition for 10 months between 2002 and 2003) and saw their vote share drop in four consecutive elections through this period. The German FDP has huge experience of government – they were the kingmakers of German politics for most of the postwar period. However, their most recent period in coalition has not been a success. Having secured an impressive 15% of the vote in the 2009 election, this week’s German election saw the party fall below the crucial 5% threshold, winning no seats as a result.

Our other two cases – the Scottish Liberal Democrats and the German Greens – offer more positive examples of how smaller parties can succeed in government. Both these parties slightly increased their vote share during two periods of government (the former from 1999 to 2007, and the latter from 1998 to 2005), though then had to leave office due to the results of other parties. Their fortunes since leaving government have varied. The Scottish Liberal Democrats suffered a very poor result in 2011, but largely due to hostility to the UK Liberal Democrats and their coalition with the Conservatives at Westminster. The German Greens have done better in opposition. While this week’s German election result was a disappointment for the party, which had enjoyed high poll ratings earlier in the campaign, it still won a greater share of the vote (8.4%) than when it entered or left coalition. Although this is not the focus of our paper, our data also shows how NZF and D66 have recovered some lost ground since moving into opposition.

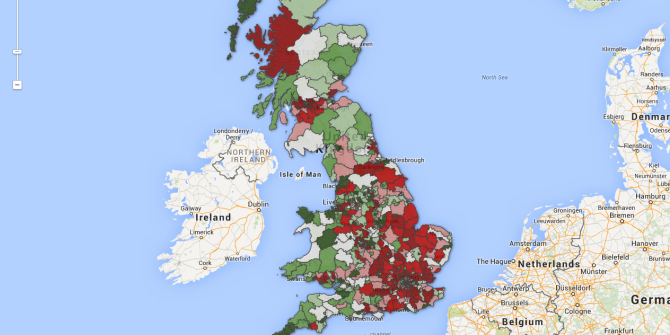

Figure 1: Electoral performance of smaller parties in and out of coalition

Based on our research into these cases (further detail of which can be found in our full paper), we extracted five lessons with relevance to the Liberal Democrats.

First, smaller parties can only distance themselves from larger coalition partners to a limited extent. Coalitions are often rewarded or punished as a whole for their performance in office. Ensuring that the government is seen as effective and competent is crucial, and particularly so for the smaller party, which will often have had less credibility at the outset as a party of administration. This will often require smaller parties to show discipline in supporting major policy initiatives of their larger partners, as when the German Greens backed Chancellor Schroeder’s Agenda 2010 welfare reforms in Germany.

But second, smaller parties also need to be able to demonstrate their distinct contribution to government to avoid what the former leader of the Irish Green Party called “the narrative of the lost moral compass”, meaning the claim that they have betrayed their principles and values (see here for work on this point). They therefore need to have some distinct flagship policy successes to point to at the next election (as the Scottish Liberal Democrats were able to do with free care for the elderly and the abolition of up-front tuition fees at Scottish universities). But parties should pick their battles wisely – securing a concession that is seen as self-serving or irrelevant by voters can undermine the wider strategy. For instance, early in the current German coalition, the liberal FDP prioritised a VAT tax cut for hoteliers, helping a small FDP-supporting sector but alienating other voters.

Third, small parties’ success rests greatly upon the performance and profile of the party leader. Successful junior coalition partners have leaders with a strong public profile and a clear personal record of achievement in government (as did the German Greens, for instance, in Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer, who took bold action to support German intervention in Kosovo, and in opposing the US war in Iraq). Parties with weak or unstable leadership have fared poorly (like the FDP, who changed leaders in mid-term and then fought the 2013 election with a third man as their lead candidate). Nick Clegg’s decision in 2010 not to take a large departmental job, unlike his counterparts in all other coalitions we studied, has made it harder for him to demonstrate to voters a personal contribution to government. Perhaps in recognition of this, Clegg announced last week that the coalition would offer free school meals for all young children, which is the kind of signature policy he may need in May 2015 to defend against the accusations that his role in government has been simply to support a Conservative agenda.

Fourth, parties associated with the premature coalition breakdowns are rarely rewarded by voters. Smaller parties in coalition elsewhere such as New Zealand First (in 1998) and the Irish Greens (in 2011) have pulled out of coalition early in the face of unpopularity and tensions with their coalition partner. In both these cases, the party suffered a heavy defeat at the following election. In the case of NZF, this process split their own party in two as well. The Liberal Democrats determination to see the coalition through till the end therefore seems advisable. However, the German experience from 2005 – when SPD Chancellor Schroeder forced an early dissolution of the Bundestag – is a reminder that coalitions can be brought to an end due to splits within the larger (and apparently dominant) party too, even when there is a strong fixed term parliament law.

Finally, smaller parties have a limited influence over whether they remain in government or not. A party may end up in coalition even after a poor election result (as did Democrats 66 in 2003) or may return to opposition even after performing relatively well (as for the German Greens in 2005 or the Scottish Liberal Democrats in 2007). The lesson here for the Liberal Democrats is to therefore make the most of the rest of this Parliament, and seek to achieve as much as possible before 2015.

The full paper is available here.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Akash Paun is a fellow of the Institute for Government. He leads the Institute’s work on the challenges of coalition government and accountability arrangements in Whitehall, and has previously conducted research on parliamentary reform, candidate selection processes, and devolution in the UK. He formerly worked at the Constitution Unit, UCL.

Akash Paun is a fellow of the Institute for Government. He leads the Institute’s work on the challenges of coalition government and accountability arrangements in Whitehall, and has previously conducted research on parliamentary reform, candidate selection processes, and devolution in the UK. He formerly worked at the Constitution Unit, UCL.

Robyn Munro is a researcher at the Institute for Government. She is currently working on a project on how coalition parties prepare for elections. She previously worked for a public affairs consultancy and holds an MSc in Public Policy from the University of Bristol.

Robyn Munro is a researcher at the Institute for Government. She is currently working on a project on how coalition parties prepare for elections. She previously worked for a public affairs consultancy and holds an MSc in Public Policy from the University of Bristol.

4 Comments