Lee Elliot Major, Andrew Eyles, and Stephen Machin present new data around public support behind the implementation of job guarantees, the reform of A-level and GCSE exams in 2021, and the abolition of predicted grades for university offers.

Lee Elliot Major, Andrew Eyles, and Stephen Machin present new data around public support behind the implementation of job guarantees, the reform of A-level and GCSE exams in 2021, and the abolition of predicted grades for university offers.

There are serious concerns that the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic may hit even harder than the first. What should we do to limit further widening inequalities in employment and education occurring as we brace ourselves for England’s second national lockdown? Our research points to effective policies that could help limit further damages to inequality and social mobility. According to our recent survey data, they have widespread public support. The results come from the first LSE-CEP Social Mobility Survey of 10,010 individuals aged 16 to 65 contacted between 14 September and 12 October 2020, combined with analysis of the April 2020 Understanding Society COVID-19 Survey tracking just under 18,000 individuals across the UK.

Job guarantees

In the face of a second lockdown and with the spectre of long-term unemployment appearing more and more likely, Chancellor Rishi Sunak has announced the return of furlough payments, covering 80% of wages for those unable to work during the new lockdown. We believe the time has now come to consider bolder longer-term job retention schemes.

Our survey reveals higher levels of worklessness than indicated by official measures. Overall, 5.4% of people employed before the pandemic hit report losing their job by September 2020. However, a further 7.3% reported still being in work, but working zero hours. Overall, the rate of not working is 12.7%. That is one in eight of the workforce, or over four million people effectively not working. Those most affected are younger people, the self-employed, and those from poorer backgrounds. For example, the rate of worklessness is twice as high for 16-25-year-olds as compared to 26-65-year-olds.

We need to do all we can to avert the catastrophe of long-term unemployment. Evidence from the 1980s shows this scars lives permanently, with individuals experiencing long-term unemployment, having permanently worse earnings and job careers, experiencing well-being and mental health problems, with negative spillover effects on to their families and communities. We have previously argued that job guarantees should be introduced for people who are, or in danger of becoming, long-term unemployed. The case is even stronger now as unemployment spells are lengthening, as individuals who have lost their jobs cannot find new positions of work.

Job guarantees are not new. The Future Jobs Fund introduced at the end of the last Labour government appeared successful, and the Youth Training Schemes of the 1980s offered work guarantees to the young unemployed. India has job guarantees in rural areas under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act of 2005, and there is serious discussion of urban job guarantees being introduced in the pandemic era; a trial by Oxford University economists is already underway piloting unconditional job guarantees in Austria. More trials could assess a range of New Deal-type initiatives. One idea is a National Youth Corps guaranteeing jobs paid at least the minimum wage for younger workers, which is especially relevant for sustainable jobs. We suggest in our latest book, a National Social Mobility Service for students and graduates to tutor disadvantaged children or to provide mentoring in the workplace.

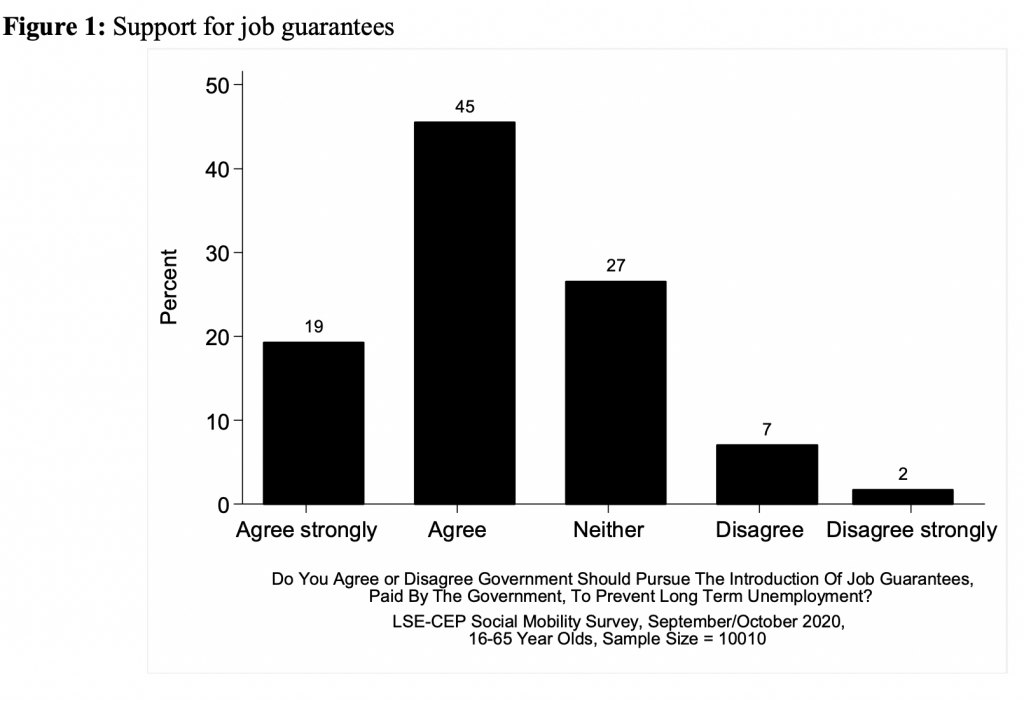

The policy is popular, especially in the current climate. In our survey, a clear majority – 64% – of respondents agree or strongly agree government should introduce job guarantees to avoid long-term unemployment, as Figure 1 shows. Hardly anyone thinks it is not a good idea. A small minority say they do not – 7% disagreed and only 2% strongly disagreed. The support broadly holds true across the political spectrum. For example, even amongst those who voted Conservative in the 2019 election, a majority (57%) said they agree or strongly agree that a job guarantee should be pursued to prevent long-term unemployment, and just under 15% disagreed with the policy.

Fair exams

Our research also reveals substantial disruption to online teaching and learning during the pandemic, despite the best efforts of schools. We estimate that four in ten school pupils received full-time schooling during the April school closures, with a quarter receiving no teaching at all. These overall figures mask stark variations in online provision: for example, three quarters (74%) of private school pupils were benefitting from full school days – nearly twice the proportion of state school pupils (38%). To prevent further inequalities in learning access, these data are supportive of the position to keep schools open during the winter lockdown and maintain face-to-face teaching. The quantity and quality of online teaching is likely to vary considerably across the education system despite clearer expectations now in place for schools. There are also benefits to young people’s wellbeing of going into school, although this has to be balanced against the concerns over the health and wellbeing of teachers.

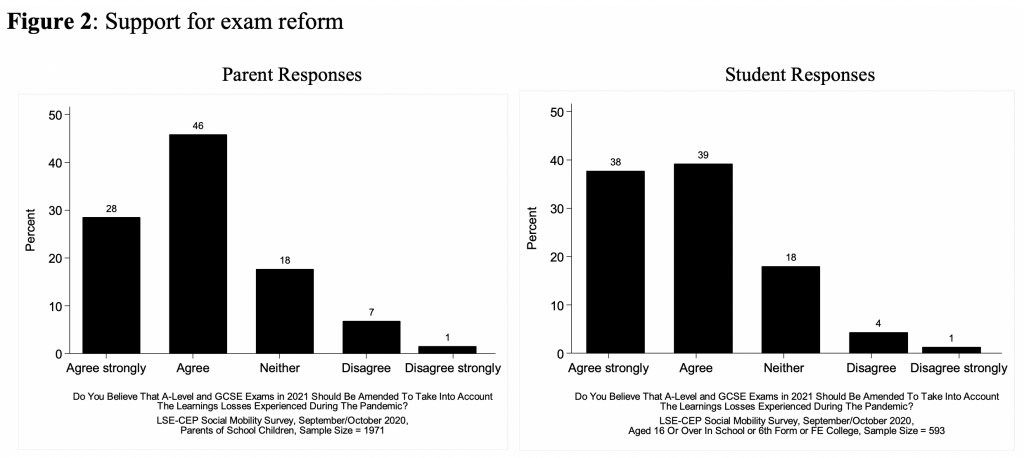

But there are serious concerns and worries about the impact of unequal learning loss during lockdown before children returned to school on exams they will take in future. Around three quarters in our survey agreed or strongly agreed that A-level and GCSE exams in 2021 should be reformed to take into account the learning losses experienced during the pandemic. Only 8% of parents and 5% of sixth form students disagreed as the charts in Figure 2 below show. The survey also found strong support among university students for exam reform.

This highlights widespread belief that pupils should not be unfairly treated in their 2021 assessments, particularly given more disruption to their learning is likely over coming months. Options might include slimmed down tests or tests with more optional questions, alongside a credible Plan B to use quality assured teacher assessments if exams become unviable. The key word here is fairness. There will be uproar if the 2021 cohort of pupils do not receive the same (higher) proportion of top grades awarded to the 2020 cohort. And there will be difficult questions if Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland adopt different approaches to England.

What is clear is that the current policy in England of delaying end-of year exams by three weeks in will not be enough to assuage growing concerns among parents, pupils and teachers.

Fairer university admissions

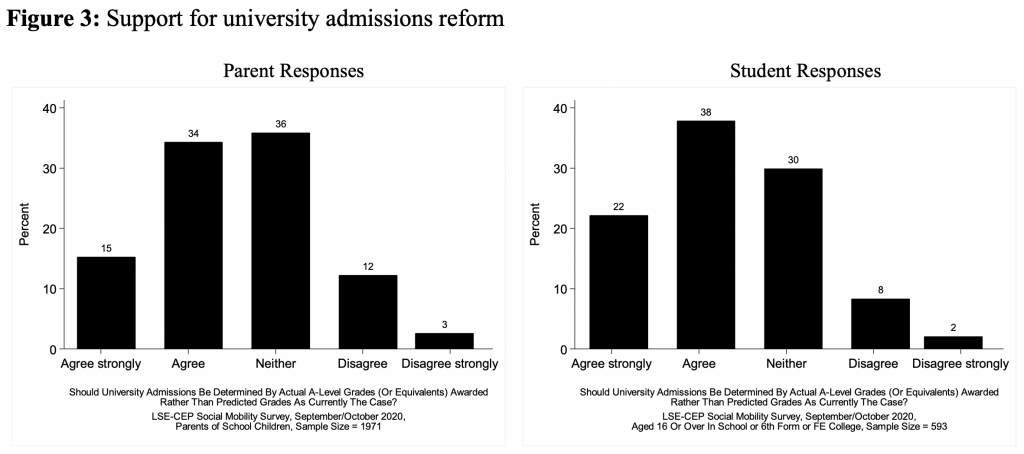

Finally, our Social Mobility Survey also finds support for moving to a post-qualification application scheme for university admissions. Again, this is true of parents of school children and of sixth form students currently in full-time education. As the charts in Figure 3 show, 49% of parents and 60% of sixth form students agree or strongly agree that universities should judge student applicants on their actual grades rather than predictions by their teachers. This compares to 15% of parents and 10% of students who disagree or strongly disagree, with 36% of parents and 30% of students remaining neutral on the question. The survey also found strong support among university students for PQA.

We have argued it is time to remove this British oddity of using predicted grades for admission offers. The most obvious flaw of the current system is that predicted grades are wrong most of the time. Teachers are becoming less accurate in their academic forecasting with each academic year. This inaccuracy is set to reach new levels in 2021, with teachers basing predictions on students who have been absent for much of the school year. High-achieving students from disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to be under-predicted (by around half a grade) than their more privileged counterparts. Current government reviews suggest that there may finally be political momentum behind the reform to tackle the logistical challenges of setting school exams earlier and enrolling university students later in the year.

For 2021 at least, we need assurances that universities (as well as colleges, sixth forms and employers) will make even greater efforts to identify and enrol talented pupils from poorer backgrounds who, through no fault of their own, have slipped a grade this year. That means more systematic lower grade offers for those pupils who can show they have been particularly disadvantaged. Our survey found that two thirds of university students agreed with the policy of lowering entry grades for students from poorer backgrounds.

_____________________

Note: this research is funded by the Economic and Social Research Council as part of the UK Research and Innovation’s rapid response to COVID-19. The authors gratefully acknowledge this funding under grant number ES/V010433/1. The research also recently featured on BBC TV Panorama. See also What Do We Know and What Should We Do About Social Mobility? published by SAGE.

Lee Elliot Major is Professor of Social Mobility at the University of Exeter and an Associate of the Centre for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics.

Lee Elliot Major is Professor of Social Mobility at the University of Exeter and an Associate of the Centre for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics.

Andrew Eyles is a research economist in the education and skills programme at the Centre for Economic Performance.

Andrew Eyles is a research economist in the education and skills programme at the Centre for Economic Performance.

Stephen Machin is Professor of Economics and Director of the Centre for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics.

Stephen Machin is Professor of Economics and Director of the Centre for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics.

Photo by Jesus Kiteque on Unsplash.