Jeevun Sandher paints a profile of the UK’s key workers. He explains how these people, a significant proportion of whom were not born in the UK, have spent the last decade earning less and being treated worse than other workers.

Jeevun Sandher paints a profile of the UK’s key workers. He explains how these people, a significant proportion of whom were not born in the UK, have spent the last decade earning less and being treated worse than other workers.

The first doctor to die of COVID-19 as it began to flow through these shores was not born in the United Kingdom – Dr Alfa Saadu, who had spent 40 years working for the NHS before succumbing on 31 March was an immigrant, as were the next seven doctors to die from the virus at the time of writing. Like all key workers whose jobs are ‘critical to the COVID-19 response‘, they are going to work today so that the rest of the public can stay at home and stop the pandemic from flooding the NHS. This makes it all the more iniquitous that, as a direct result of government policy, they’ve also been more likely to see their earnings fall, hostility towards them rise, and are now being forced to pay extra charges to use the same health service they keep from sinking.

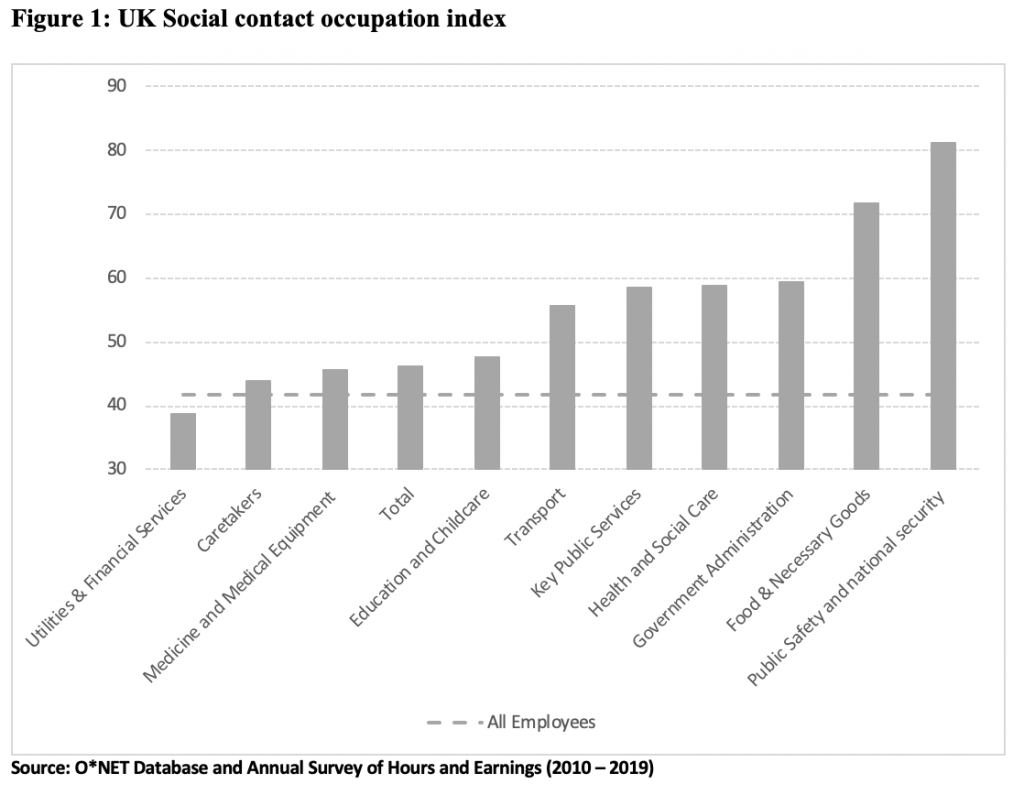

Key workers are clearly more at risk of currently contracting coronavirus. What is less obvious is that because their jobs also require more social interaction than other occupations in normal times, they were also at more risk of contracting the virus before the lockdown was imposed and will also be more vulnerable after it is lifted. Using the same methodology and data as employed in studies of automation, I’ve constructed a Social Contact Occupation index based upon how important it is to, ‘Perform or Work Directly with the Public’ for each job (using the O*NET data base). It ranges from 0 to 100 and the weighted average for Key Worker job categories as well as all occupations is shown in Figure 1 below.

On average, social contact is around 30% more important for all key workers, 40% more important for Health, and 70% more important for Food workers than it is for the UK’s workforce as a whole. While this index does not fully reflect the risks that Health and Social Care workers are bearing – it only measures how likely an individual is to come into contact with unknown members of the public as part of their job, not how likely it is that these members have coronavirus – it should not detract from the risks non-health key workers are facing in their daily working lives.

Governments across the globe have had to drastically limit social contact because COVID-19 is both highly infectious and can spread from people who do not show any symptoms; simply coming into contact with more people, as key workers are every single day, puts one at a much greater risk of contracting the disease. And while the current focus is, rightly, on ensuring that Health & Social Care workers receive personal protective equipment, the next priority should be to guarantee an adequate supply for all key workers.

Wages

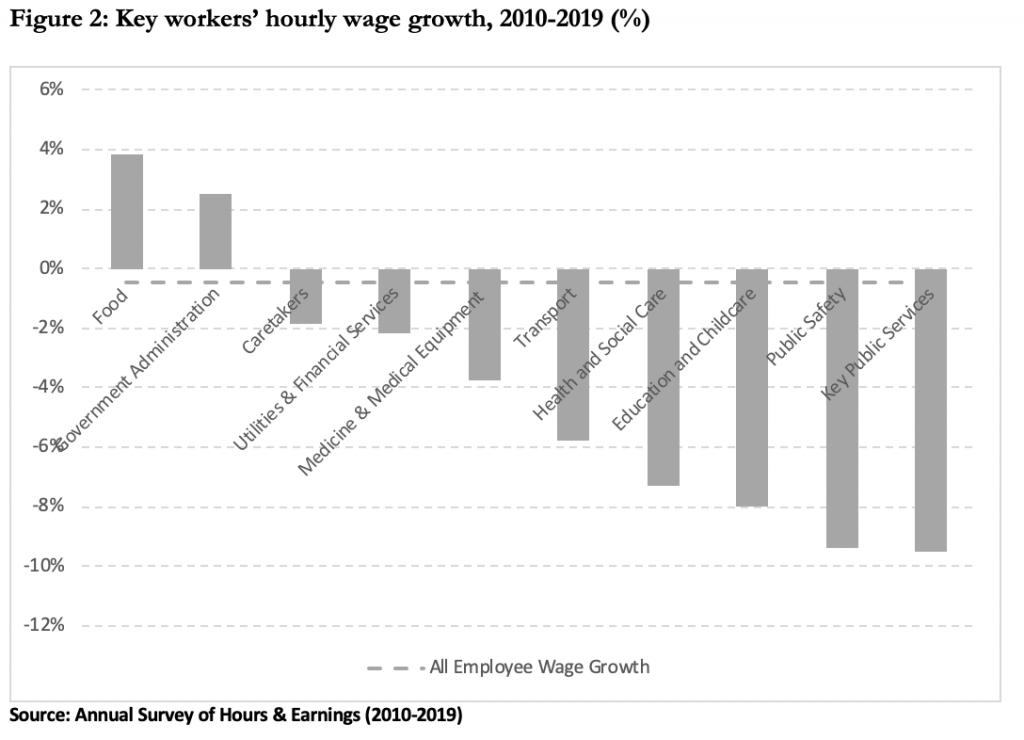

Key workers are placing themselves at greater risk to keep the nation afloat during this pandemic but have spent the last decade sinking further below everyone else – their hourly earnings have fallen by over 4% over the past ten years, while earnings for all workers fell by only 0.3% as shown in Figure 2. Even the glittering performance of rising wages in the food sector is deceiving: while large increases in the minimum wage led to an accordingly large rise in earnings, higher pay was met with with social security cuts, leading to low-paid key workers in poorer households seeing their incomes fall even as their pay has risen. Reversing these cuts and increasing the incomes of all poor key workers would be a fitting reward when the clapping stops.

For those employed in the public sector, a decade of pay restraint has not only left currently employed key workers poorer, it has also led to falling recruitment and dangerously understaffed public services. Health and Social Care staff have seen their hourly earnings fall by 7.5% since 2010 and before this pandemic hit, the NHS already had a staffing shortfall of 100,000 healthcare workers, one in eight nursing vacancies were unfilled, and more than half of consultants said this had damaged patient safety.

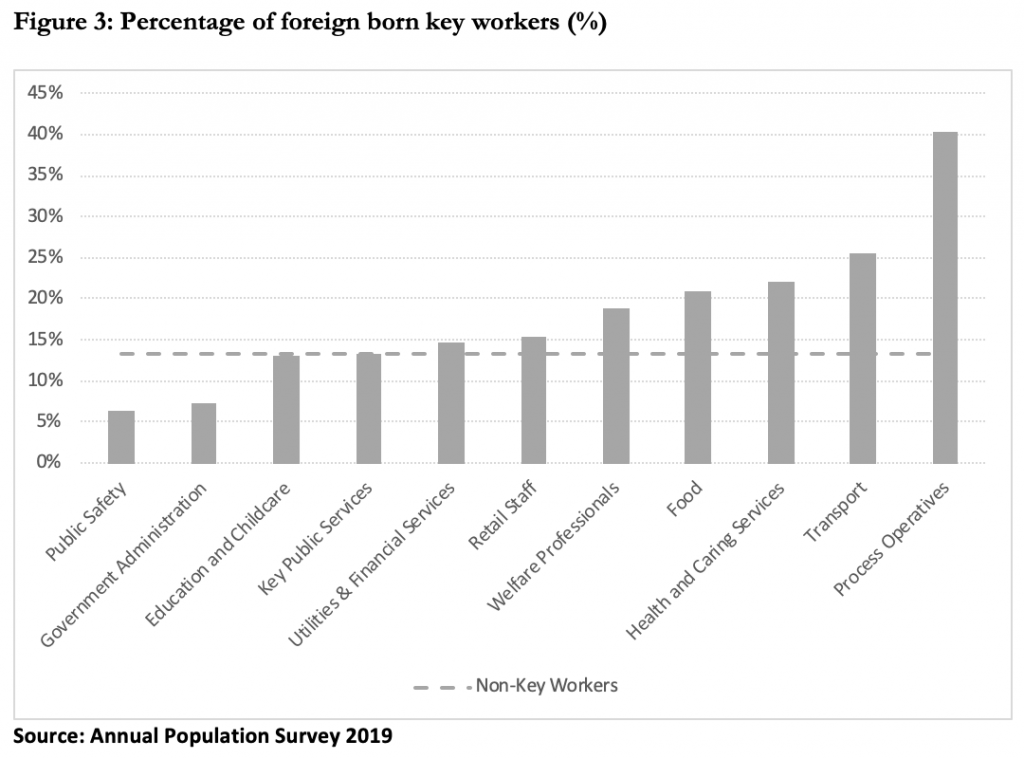

Since its creation, the NHS has relied on immigrants to function but this did not stopped governments from using them as scapegoats for their own health policy failures nor from creating a hostile environment that has led to a rise in anger and fear directed toward, as well as felt by, all ethnic minorities. In today’s crisis, we are all relying on immigrants who are over-represented in Key Worker categories (Figure 3) – more than one in five Health and Social Care workers were born abroad. That has not, however, stopped this government from charging them £400 each per year (rising to £624 in 2021) to use the health system they keep functioning. It was admirable for the Prime Minister to praise the foreign nurses who treated him; it is indefensible that he asks them to pay for the privilege of keeping him alive.

It has not, nor will it be, the fruits of our common endeavour that will pull us thorough this storm. Instead, it is the often-foreign few to whom the many are indebted. But these key workers, who will continue to risk their lives every single day for the foreseeable future, have also spent the last decade earning less and being treated worse. It is time to fix that and repay them for the risks they are taking for us all.

____________________

Jeevun Sandher is a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Economy at King’s College London.

Jeevun Sandher is a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Economy at King’s College London.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: by K. Mitch Hodge on Unsplash.