The principle of making certain bodies independent from government, such as regulatory agencies or central banks, has become popular in a number of contexts over recent decades. As Jacint Jordana and Guillermo Rosas write, the basic assumption underpinning the principle is that electoral pressures can have a negative effect on decision-making in certain policy areas. However, using evidence from a study of banking regulatory agencies across 81 countries, they illustrate that the benefits of independence depend largely on the political context within a given state. This suggests that while independence can be beneficial in some cases, greater attention should be paid to the individual circumstances within particular countries.

The principle of making certain bodies independent from government, such as regulatory agencies or central banks, has become popular in a number of contexts over recent decades. As Jacint Jordana and Guillermo Rosas write, the basic assumption underpinning the principle is that electoral pressures can have a negative effect on decision-making in certain policy areas. However, using evidence from a study of banking regulatory agencies across 81 countries, they illustrate that the benefits of independence depend largely on the political context within a given state. This suggests that while independence can be beneficial in some cases, greater attention should be paid to the individual circumstances within particular countries.

It is not uncommon to hear experts claim that many public policy problems could be solved by granting more independence to the professionals in the public sector who are responsible for managing these policies. They sometimes suggest that the best way to solve the complex problems of democracy is to completely separate ‘technical’ policy decisions from the political process.

The implicit assumption is that the quality of public decisions is improved when they are removed from the political sphere. From a democratic legitimacy perspective, these suggestions are certainly debatable, and are only warranted, at least partially, when adequate control and accountability mechanisms are in place. We would argue, however, that independence does not solve everything, and sometimes serves no purpose at all.

We do not argue against the safeguards of independence in any entity or public organisation. In many instances there are reasonable grounds for introducing independence. Politicians and legislators can protect non-elected civil servants to allow them to make demanding decisions if they feel this is the best way to get good results in terms of public policy.

By tying their own hands to make certain future decisions more difficult, politicians avoid some of the pitfalls created by democracy, such as the intense competition to attract voters, the immediate weight of public opinion, and the rapid discounting of the future that is tied to the political cycle. These practices are not unique to the political arena. Decision-making mechanisms designed to avoid succumbing to future temptations are present in many areas of our public and private lives, as Jon Elster frequently reminds us, and it is understandable that such mechanisms are used to make democracy function properly.

Our approach focuses on the risks associated with generalising the potential merits of independence. We have known for some time that the stability of civil servants, regardless of changes in the political arena, has positive implications for the smooth functioning of public administration. This is certainly the case, but we must distinguish between the implementation of policies and the decisions that drive them, which often have components that are not purely technical in nature.

It is not an easy line to draw, of course, nor is it viewed the same way everywhere. Nonetheless, it is important to acknowledge that defining this line constitutes a huge source of tension, often with pressure from both sides. We encounter policymakers who are obsessed with deciding every last detail of public management, and professionals and bureaucrats who want to impose their own political priorities. We are not going to attempt to address this tension here, but we highlight the fact that calling for independence may be part of the struggle to redefine the distribution of power within the public sphere, and identify comfort zones that prevent tension between political control and technical capacity.

Independence of banking regulators

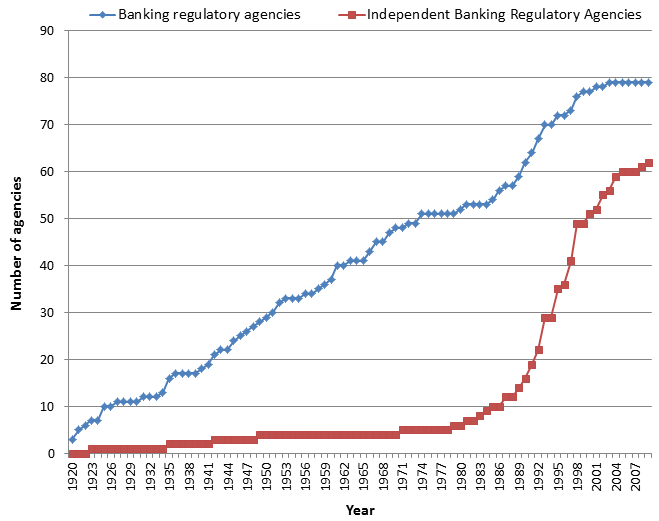

We have recently conducted a research project which helps to illustrate our argument. First, we confirmed the extraordinary diffusion of the banking regulation model based on the separation of banking agencies from government (regardless of whether the agency is set up within or outside the central bank). The Chart below illustrates how this model spread throughout the 20th century and the beginning of this century, and how independent agency status was adopted in many cases. The blue line shows the growth in banking regulatory agencies across the world, while the red line shows the number of these banking regulatory agencies which were independent from government.

Chart: Creation of banking regulatory agencies in a sample of 81 countries (1920-2009)

Note: For a full explanation of the methodology and the 81 countries see the authors’ journal article.

Next, we analysed the institutional banking regulation models in over 80 countries around the world in terms of their ability to prevent banking crises. We found that independence does not always guarantee greater protection against the risk of a banking crisis. This does not imply that independent banking regulatory agencies increase the risk of a banking crisis, just that there is no evidence of their effectiveness.

Indeed, we found that granting more independence to banking regulators is a good solution in countries with highly concentrated political power, but has no effect in countries where power is highly fragmented. Countries that benefit most from granting independence to their regulatory agencies are those with a presidential regime and weak parliament, or those with a parliamentary regime where a single political party frequently has an absolute majority (as occurs in Spain). In countries where political power is fairly fragmented (such as the US), giving greater independence to regulators slightly tilts the tension between technical professionals and politicians (including legislators) in favour of the professionals, without necessarily reducing the likelihood that the banking system will experience widespread insolvency.

Avoiding impulsive decisions or opportunistic strategies can reduce the risk of banking crises, but a democracy with fragmentation of power, which requires a slow, complex decision-making process, is in itself an institutional obstacle that essentially renders the regulatory agency’s independence superfluous. When there are no such obstacles, independence enables the agency to serve as a functional substitute. Of course, in a situation where power is concentrated, the agency itself can be overpowered if the motivation or political interest is great. However, the political cost, time and effort involved in closing a regulatory agency or reversing its decisions are considerable impediments that place the agency in a strong position of stability, especially if it is performing well.

In this regard, the risk of dismantlement of a regulatory agency by the political authorities as a punishment for not fulfilling its mandate constitutes a strong incentive to carry out its duties as effectively as possible. By contrast, in cases where an independent agency perceives that the risk of intervention or termination is very low, it may relax the level of effort required to achieve its objectives, given the lower perceived pressure and increased security of its comfort zone.

Paradoxically, the existence of multiple centres of power makes the independence of regulatory agencies less effective, precisely because independence itself is more credible. In these circumstances, the agency’s passive attitude to risk increases; in addition, the existence of many centres of power limits the likelihood of making impulsive decisions (which causes the agency to relax even more).

We can surmise from all this that independence for regulatory agencies is not a concept that can simply be proclaimed as ‘better’. It is important to have a proper understanding of the political structure of a country, its structure of institutional checks and balances, and the characteristics of the sector in which the agency operates, including the visibility of its actions in order to identify the most appropriate requirements for independence. Thus, for example, we anticipate that no major public advantages or benefits will emerge in the banking sector as a result of the exceptionally high level of independence of the European Central Bank now that it is also a banking regulator.

Note: The English version of this article was originally published on our sister site, the LSE’s EUROPP blog, and gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before commenting. Featured image credit: Gizmo23 (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Jacint Jordana is professor of Political Science and Public Administration at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra. He has been visiting fellow at the Australian National University, Wissenschafts Zentrum Berlin, University of California (San Diego) and Konstanz University.

Jacint Jordana is professor of Political Science and Public Administration at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra. He has been visiting fellow at the Australian National University, Wissenschafts Zentrum Berlin, University of California (San Diego) and Konstanz University.

Guillermo Rosas is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at Washington University in St. Louis.

Guillermo Rosas is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at Washington University in St. Louis.