There is much we don’t know about post-legislative scrutiny, one being the strength of recommendations made and the acceptance of those by the government. Thomas Caygill explains that committees are mostly producing recommendations which are calling for small and lower medium action, possibly because weaker recommendations are more likely to be implemented.

There is much we don’t know about post-legislative scrutiny, one being the strength of recommendations made and the acceptance of those by the government. Thomas Caygill explains that committees are mostly producing recommendations which are calling for small and lower medium action, possibly because weaker recommendations are more likely to be implemented.

Once legislation has entered the statute book, there are some who assume that is the end of the matter and the end of Parliament’s role. However the House of Lords Constitution Committee stated that Parliament’s responsibility for legislation should not end once a bill has become an Act. This is where post-legislative scrutiny comes in. It is defined by the Law Commission as a ‘broad form of review, which addresses the effects of legislation in terms of whether intended policy objectives have been met, and if so, how effectively’.

In the last decade a more systematic approach to post-legislative scrutiny has been taken by both government and Parliament, with the House of Lords Liaison Committee in 2012 promising to appoint at least one ad hoc committee per session, while since 2008 government departments have been required to prepare and publish memoranda, assessing whether an Act has met its key objectives, within three to five years of it entering the statue book. These memoranda are then presented to departmental select committees for additional scrutiny.

However, while we know what post-legislative scrutiny is and that it is undertaken by committees in both Houses of Parliament, there is a lot we do not know. Here, and drawing on my PhD research, I will focus upon what recommendations committees are making following post-legislative inquiries and whether the government is accepting them.

There are three areas which this article will cover: the strength of recommendations, the acceptance of those recommendations by the government, and the acceptance of recommendations by their strength. These three areas are important as we currently do not know what the output of post-legislative scrutiny has been despite it being a core task of departmental select committees in the Commons.

In terms of the strength of recommendations that committees are producing, the research has shown the following breakdown;

- No Action – 3%

- Small Action (e.g. information to be released) – 40%

- Medium A Action (e.g. additional resources) – 20%

- Medium B Action (e.g. new regulations) – 29%

- Medium C Action (e.g. substantial amendments to an Act) – 9%

- Large Action (e.g. new legislation) – >0.5%

This data has been collated from the recommendations contained in seventeen post-legislative scrutiny reports between 2005 and 2016 and shows that 43% of recommendations called for no or small action on behalf of the government. Recommendations which called for some kind of medium action on behalf of the government totalled 58% and there were only two recommendations out of 417 that were classified as calling for a large action.

The data suggests that committees tend to focus their recommendations on ones calling for small and lower medium actions – accounting for nearly two-thirds of recommendations (no, small, and medium A combined). This could be a response to knowing they do not have the power to force the government to accept and implement their recommendations. As a result committees may wish to hedge their bets and recommend small and medium actions which are more likely to be accepted by the government. This strategy has been acknowledged by both Meghan Benton and Meg Russell and also by Malcolm Aldons. Although my research interviews suggest that weaker recommendations could be made for one of the following three reasons;

- Internal political compromise: committees know that a unanimous report is more influential, and try to achieve consensus. That sometimes means that they prefer a weaker recommendation on which they can all agree, rather than a stronger one which would cause a division.

- Seeking compromise with the Government – committees recognise that they won’t get everything they want. They sometimes judge that it would be better to get something (to address whatever problem they have identified) than nothing.

- Lack of evidence. Sometimes committees just don’t have the evidence to make a strong recommendation. There are some recommendations that would count as weak, because they ask for reviews or consideration rather than action. But that could at least in part due to not having the evidence base to support a strong recommendation.

However in my research, when asking committee staff how much attention they pay to the government’s likely response to a recommendation before making it, they noted that at times they do pay some attention to this factor, but it does vary from issue to issue and from committee to committee. One additional factor worth noting is that the Acts scrutinised so far have in fact been found to be operating fairly well, and as such improved operation could be achieved with relatively minor tweaks.

With regards to the acceptance of recommendations, the research showed the following breakdown;

- No Response – 12%

- Rejected (in part and in full) – 36%

- Neither accepted nor rejected – 13%

- Accepted (in part and in full) – 39%

This data has been collated from the government responses to the seventeen post-legislative scrutiny reports between 2005 and 2016. There is somewhat of a balance here between recommendations being accepted and recommendations being rejected. With 39% of recommendations being accepted it might suggest that committees are having an impact, however it is not an ideal way of measuring impact on the basis that just because the government states that it accepts a recommendation doesn’t guarantee that it will be implemented.

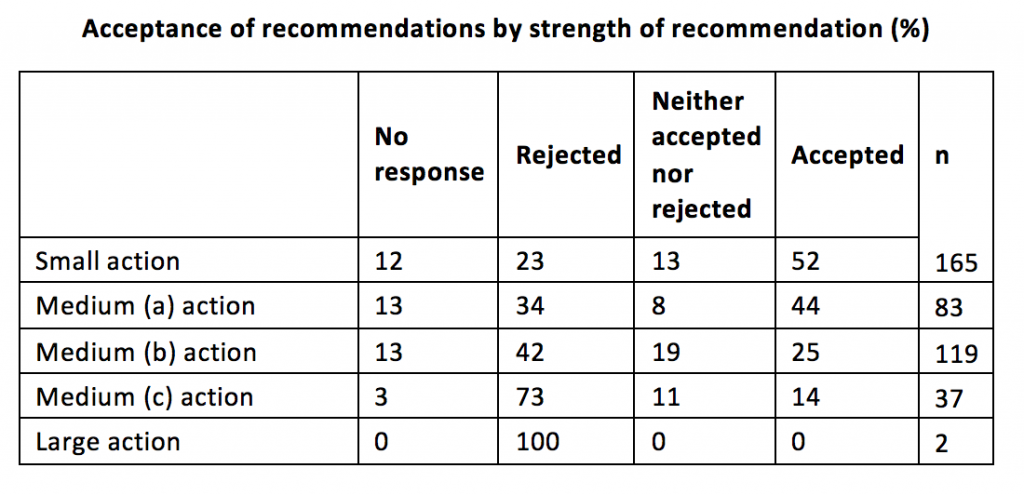

Finally, having noted that there is potentially a strategy deployed by committees in terms of producing weaker recommendations so the government is more likely to accept them, it is important to assess whether the government is in fact rejecting stronger recommendations. The table below confirms such a trend, in that as recommendations get stronger they are more likely to get rejected and in turn the weaker they are the more likely they are to get accepted.

While this does not prove that such a strategy is deployed by committees and there are indeed other reasons for why committees may produce weaker recommendations, the data might provide a reason for why committees may wish to deploy such a strategy. Indeed, the regression analysis undertaken during the broader research found that strength of recommendation was highly significant in the acceptance of recommendations, with weaker recommendations being more likely to be accepted.

Coming back to the original question, it is clear that committees are, for the most part, producing recommendations which are calling for small and lower medium action. It was noted that there is potentially a strategy at play here by committees, to produce weaker recommendations as they are more likely to be accepted. However there are a number of reasons for why committees might produce weaker recommendations. The data has also shown that the government is accepting 39% of recommendations (which is not surprising as the majority of recommendations call for no, small or lower medium action) and appears to be accepting recommendations based on their strength. Although we cannot categorically say that a strategy exists, the data in the table might provide a reason for why committees may wish to deploy such a strategy.

______

Thomas Caygill is a PhD researcher at Newcastle University.

Thomas Caygill is a PhD researcher at Newcastle University.

Featured image credit: Stevebidmead, Pixabay/Public Domain

Wouldn’t it be better to have the committee meet and make recommendations BEFORE the law is enacted?

Post legislative scrutiny seems to be a very good idea, after all not all legislation has the desired outcomes, the poll tax, for example, could have been corrected a lot quicker. Maybe someone should suggest it to the eu, although any form of scrutiny would be progress for them.