Average earnings vary widely across the regions of Britain, a fact that has prompted many decades of policies aimed at reducing regional disparities. But as Henry Overman and Steve Gibbons demonstrate, such variation reveals little, especially if we ignore regional differences in the cost of living and availability of local amenities.

Average earnings vary widely across the regions of Britain, a fact that has prompted many decades of policies aimed at reducing regional disparities. But as Henry Overman and Steve Gibbons demonstrate, such variation reveals little, especially if we ignore regional differences in the cost of living and availability of local amenities.

Regions, cities and neighbourhoods across Britain seem to be very unequal. This is true if we look at average earnings, employment, education and almost any other socio-economic outcome. Take ‘gross value added’ (GVA) per person, potentially a good indicator of living standards in different places. In 2005 (a point in time chosen to be sometime before the peak of the boom), the highest ranked regions in Britain were West Inner London and Berkshire with GVAs of £44,050 and £39,850 respectively. The lowest ranked were Liverpool and Blackpool with GVAs half those in the South East: £19,800 and £21,050.

Regional policy, urban policy, even neighbourhood policy are all largely based on concerns about these kinds of disparities. But these figures are simply aggregates of the outcomes for people who live and work in these places. Without further information, we do not know whether the outcomes for people currently living in Manchester would be any different if they lived and worked in London.

We also have no way of knowing if the productivity of London and Manchester would change if these movements of people actually took place. Similarly, we do not know whether replicating the economic, policy, institutional and environmental regime of London in Manchester would change anything without moving people. In short, it is hard to work out what these differences mean in terms of the economic advantages and disadvantages that a place offers to the people who live and work there.

Our research offers new empirical evidence on the nature, scale and recent evolution of economic disparities in Britain. We focus on disparities in individual wages, because wages are linked to productivity and they are an important cause of variation in living standards. Using these ‘micro’ data, we assess the extent of and persistence in wage disparities across labour market areas in Britain. We examine to what extent these area differences arise because of differences in the characteristics of people who live in different places – ‘sorting’ – versus different outcomes for the same types of people living in different places – ‘area effects’. We also consider the extent to which these differences across areas contribute to overall individual wage disparities.

Our research finds that between 1998 and 2008 there were few changes in area disparities, despite many policy interventions. It also turns out that who you are is much more important than where you live in determining earnings (and other outcomes). Area effects only play a small role in the overall wage dispersion.

This research suggests that wage disparities across local areas in Britain are pronounced and very persistent but that much of these disparities are driven by ‘people’ rather than ‘place’. Regardless, such disparities between different cities and different labour markets concern policymakers because they seem to imply differences in standards of living and economic welfare. But spatial earnings disparities are uninformative about differences in people’s overall wellbeing unless we take account of differences in the cost of living and the availability of local amenities.

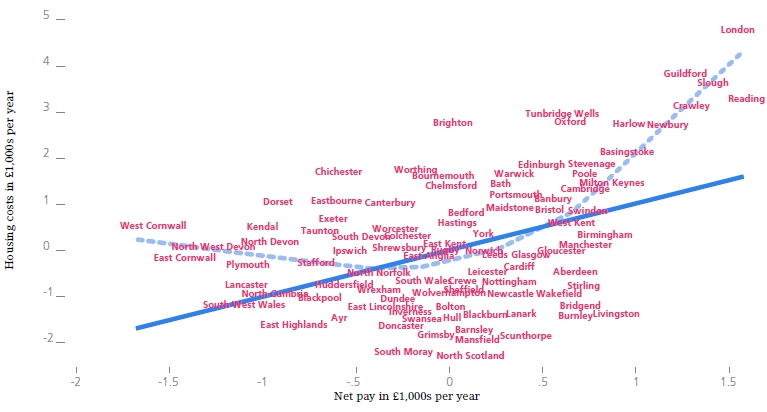

We have also considered the extent to which higher post-tax earnings are offset by higher housing costs. Figure 1 shows the results for a sub-set of 157 labour market areas. Both wages and housing costs are in £1,000s per year. The wage gaps between areas are estimated from the wage gains and losses for individuals who move between areas; and housing costs are measured from house prices, adjusting for differences in housing quality.

Figure 1: The regional relationship between earnings and house prices in Britain

The solid upward-sloping line corresponds to the case where housing costs rise one-for-one with wages. Given that most people in Britain are free to choose where they live, higher wages should translate directly into higher house prices for places that are otherwise identical. That is, we should expect £1 higher wages to mean housing costs rise by £1 per person. In fact, on average the empirical relationship in Britain is close to this theoretical benchmark.

But as Figure 1 shows, there is also a great deal of variation around this general relationship. What drives this variation is the fact that other things are not equal. Places differ in the local amenities that they provide to households. These amenities include crime, weather, pollution, entertainment and natural beauty.

Rather than focusing on area rankings, it is more useful to consider what this approach tells us about the trade-off faced by people in Britain. The dashed line in Figure 1 does this by showing how the relationship between house prices and wages changes as we move from low to high wages.

Places with lower wages in Britain tend to be rural but as wages increase, house prices tend to fall not rise (so the relationship between house prices and wages is downward sloping). This suggests that places with high levels of consumer amenities tend to have few productive advantages for firms.

In these places, consumer demand for local amenities drives up land costs and house prices, but since these areas do not offer productive advantages, wages must also be lower to induce businesses to locate there. Households in the lowest wage places are willing to pay high house prices because they are compensated by higher local amenities.

When you look at the places we are talking about – for example, West and East Cornwall, Devon and Kendal – this clearly makes sense. These are places in which ‘underperformance’ and a lack of development has gone hand-in-hand with preservation of rich natural amenities that are highly valued by consumers, even though wages are low. This high valuation of natural and recreational resources, reflected in housing costs, is borne out in more detailed analysis we have done.

In contrast, moving to higher wage areas – on the right-hand side of Figure 1 – we tend to see house prices increasing as wages rise. This suggests that local producer benefits tend to drive the relationship for higher wage areas. Firms drive up land costs in these labour markets, and workers must be compensated with higher wages to induce them to live there, but with house prices higher to offset the benefits of higher wages.

Note though, that on the far right-hand side of Figure 1, in London and the South East, amenities for consumers and productive advantages for firms tend to be positively correlated across labour markets. Housing costs rise steeply, more than one-for-one with wages, indicating that consumers are willing to pay over and above the expected wage gain to live in these areas – though here the amenities are quite different from those they expect to find in places like the South West of England and the Lake District.

So across Britain, our research shows that increased living costs (particularly of housing) tend to offset completely increased wages for the average household. In the lowest wage areas, which are mostly rural, differences in amenities drive the trade-off between wages and the cost of living. In higher wage areas, which are mostly urban, differences in firm productivity drive the results.

What are the implications of this research for urban and regional policy in Britain? We highlight four:

- Area averages are not very useful indicators of wellbeing: Differences in average incomes across neighbourhoods or regions reflect the interaction of area effects and the sorting of people. High wages tend to be offset by high house prices or low quality of life so income differences on their own are not very useful indicators of differences in wellbeing.

- Policy should be assessed by its impact on people not places: People trade off wages, cost of living and amenities, and they can move in response to changes in any of these. As a result the impact on observed area differences offers a very poor guide to the overall effects of policy on individuals.

- In practice, policy has probably been too heavily focused on places: Area effects mean that living in some places negatively affects individual outcomes. The usual response is to try to improve ‘bad’ areas. An alternative would be to focus on improving outcomes for people who live in bad areas. The focus on area differences biases policy towards the first response. Unfortunately, evidence suggests this has not been successful as area effects are very persistent. This argues for a greater focus on improving outcomes for individuals including, possibly, removing barriers that prevent people relocating to better areas.

- Policy has paid too little attention to house prices and amenities: Planning decisions play a key role in generating area disparities because people and firms sort in response to both wages and local costs. Similarly, disparities in amenities matter because high quality of life compensates people if wages are low relative to the cost of living. Local policy-makers have policies that directly affect house prices and amenities and relatively few that affect wages and employment.

At a time of constrained finances and weak economic performance it is more important than ever that urban and regional economic policy focus on sensible objectives using cost effective policy levers. Reflecting these four key insights when considering how policy should be targeted and developed would be a useful step in the right direction.

Please read our comments policy before posting.

This article first appeared in the Autumn 2011 edition of the LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance Magazine, CentrePiece.