David Binder examines new research showing the hardening of public attitudes towards welfare recipients. He argues that the media has, and continues to play a major role in defining perceptions around welfare, making it easier for those in political power to pursue similar language and engage in policies that sit well with such perceptions.

David Binder examines new research showing the hardening of public attitudes towards welfare recipients. He argues that the media has, and continues to play a major role in defining perceptions around welfare, making it easier for those in political power to pursue similar language and engage in policies that sit well with such perceptions.

In the midst of uncertain economic times, where debates around welfare spending and benefit recipients are as keenly contested as ever, and where UK society is witnessing seemingly unprecedented welfare reform, new research conducted by Natcen (the National Centre for Social Research) funded by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and the Department for Work and Pensions offers some fascinating analysis on how public attitudes toward welfare and welfare recipients have changed between 1983 and 2011.

Attitudes to welfare spending

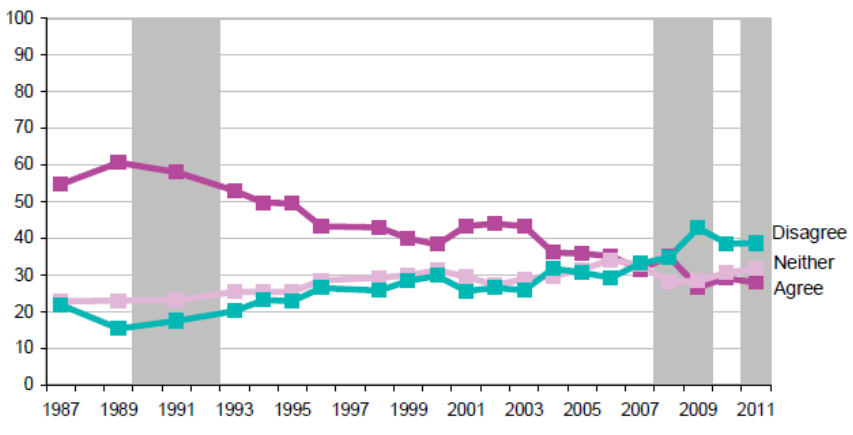

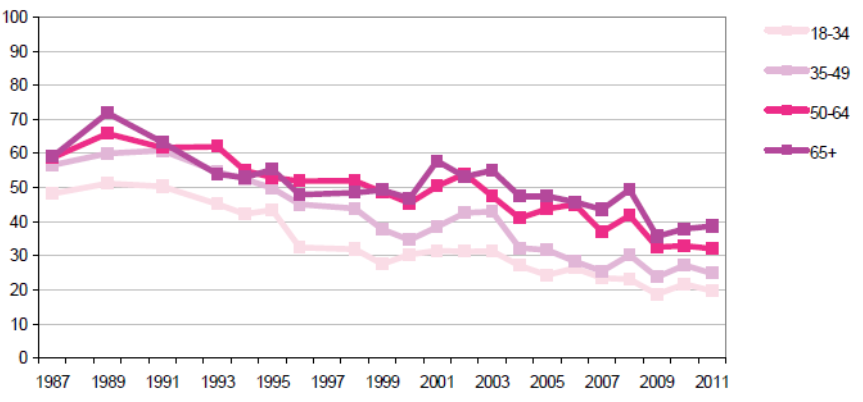

Support for welfare spending on the poor has consistently declined over the past three decades, with this decline in support being particularly pronounced amongst Labour Party supporters, and the young (that is, those aged 18-34). This is intriguing given that the Labour Party is traditionally seen as the party generally in support of higher welfare spending, and the young are particularly exposed to the risk of unemployment, especially during recessions. The below graphs illustrate the decline in support for welfare benefits for the poor.

Figure 1: Views on whether the government should spend more on welfare benefits for the poor, by UK recessions, 1983-2011

Figure 2: Per cent agreeing government should spend more on welfare benefits for the poor, by age, 1987-2011

Causes of Poverty

While views about the causes of poverty have remained generally stable, the popularity of a societal explanation has declined in favour of responsibility being placed on the individual, this being true across the political spectrum and age ranges. Indeed, as the authors point out:

Nevertheless, there has been considerable fluctuation in perceptions of the causes of poverty over time. Specifically, the explanation that living in need is due to the individual’s own characteristics and behaviour (“laziness or lack of willpower”) has gained popularity at the expense of a societal explanation (“injustice in our society”). 15% of the public in 1994 thought people live in need because of laziness or a lack of willpower, compared with 23% in 2010. During the same period, adherence to the view that people live in need because of injustice in our society declined from 29% to 21%.

Intriguingly, the decline in popularity for a societal explanation for poverty in the UK has been confined to Labour Party supporters (as was the case regarding attitudes to welfare spending), 41% of Labour Party supporters in 1986 thought that people lived in need because of injustice in society, compared to 27% in 2010.

Perceptions of welfare and benefit recipients

The report found that in 2011, negative perceptions of welfare recipients were held by considerable minorities of the population, whilst those in receipt of unemployment benefits were viewed pessimistically in terms of their ability to find a job by an outright majority.

In terms of the other findings in this area, slightly more than one third agreed that most people on the dole are fiddling (37%) and that many people who get social security don’t really deserve any help (35%). More than half (56%) agree that most unemployed people in their area could find a job if they wanted one.

Views relating to these issues have altered over time. In 1989, more than half (52%) thought that most people in their area could find a job if they wanted one, a proportion which declined to 38% in 1991 (during recession) and 27% in 1993 (after recession). Although the recessionary impact is less stark, in 2008, at the start of the late 2000s recession, almost seven in ten respondents (68%) believed that most unemployed people could find a job if they wanted one. By 2009, this proportion had fallen to slightly more than half (55%), remaining at this level in 2010 and 2011 (as already mentioned above.) Thus, whilst there have been considerable fluctuations in between 1989 and 2011, the 2011 percentage is actually rather similar to what it was in 1989.

Much to chew on then, and whilst this report excellently highlights both the hardening in attitude and consistently negative attitude toward welfare spending and those claiming benefits, a natural progression on from this would be to consider why such a hardening of attitude has occurred within this time period.

Why have attitudes hardened?

In an article regarding attitudes to welfare, Chris Goulden, head of Poverty at the Joseph Rowntree Foundation noted that in his view:

The hardening of attitudes towards benefit claimants has arisen in part from a perceived ‘success’ of Labour policy in reducing out-of-work family poverty. The bitter irony is that childless, unemployed adults now – likely to be at the forefront of public ire about ‘scroungers’ – are the one group who have become persistently worse off over the last 30 years.

In other words, Goulden suggests that ‘success’ in terms of reducing poverty via a more ‘generous’ benefits and tax credits system introduced under New Labour (whether the New Labour reforms were successful or generous is open to much debate) appears to coincide with a rise in hostility as observed in the report.

Personal reflections

The media have a very considerable role to play in influencing perceptions and constructions of those receiving welfare and benefits. Indeed, the role of the media in influencing public perceptions on various issues has increased no end in the past 30 years in correlation with technological developments in computing, communication and information sharing.

In looking at some national newspaper websites for example, it’s easy to see how those on benefits are portrayed. Indeed, on the MailOnline site rarely a day goes by without a story of an individual, couple, or family fiddling the system for ‘immense personal gain’. Such persistent and negative portrayals of a minority only serve in my view to paint a picture that essentially brands all those in receipt of benefits as ‘scroungers’, or the UK welfare system as an overwrought and broken machine in urgent need of punitive reform. Whilst indeed there are a minority who abuse the system in a welfare and benefits apparatus that can be significantly improved in a number of ways, it’s also true that for every story of benefit or welfare abuse, there’s at least another somewhere of someone whose worked hard for x amount of years, finds themselves laid off through no fault of their own and is back in work again paying their way after receiving some sort of welfare payment for a short period of time in the interim. Whilst the Daily Mail and others who consistently produce this sort of output will argue that they are merely reporting on a minority, such consistent scaremongering paints a picture that unquestionably is in danger of tarring all who claim benefits with the same brush as those who abuse the system, as indeed can be seen in the findings of this particular report.

Indeed, figures published by the DWP demonstrate that benefit fraud in the form of overpayments accounts for just 0.7% of total expenditure.

How we decide who is ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ in this whole arena is an important question for another day. For now however, the way the mainstream media paint welfare, benefits and those in receipt of them matters crucially because those in power and policy makers clearly listen to these portrayals in making policy in this area (although admittedly this isn’t the only influencing factor operating in policy making.) Evidence of this is evident through political strategizing and speeches made by the mainstream parties. Note for example, how then Labour Party leader Tony Blair espoused a new ‘tough rhetoric’ around welfare during his leadership in order as many argue, to gain the affections of ‘Middle Britain’ and win over the tabloids. Note also how this toughening of welfare rhetoric has been used by the Conservative Party in recent times, with George Osborne claiming at the Conservative Party conference in 2010 that under the Coalition there would, for welfare and benefit recipients be ‘no more open-ended chequebook.’ Quite apart from the fact that it is highly questionable as to whether there ever was such a generous ‘open chequebook’ under New Labour, his kind of language again demonstrates a hardening of attitude that is becoming increasingly pervasive in mainstream politics.

Hence, whilst those in power at present will argue the on-going economic crisis warrants such hard rhetoric, it is no coincidence that this continued hardening of attitudes towards welfare and its recipients from our media makes it easier for those in political power to pursue similar language and engage in policies that sit well with such perceptions. How this media portrayal sits with the general public (indeed, it appears to be supported by them), and is influenced by them is a much more complex question. What is absolutely clear however is that somewhere along the line the media has, and continues to play a major role in defining perceptions around welfare, its role in UK society and those of its recipients.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

David Binder is a Family Fiscal policy Consultant for the Christian social policy charity, CARE, where he conducts in- depth research on Family Tax, Welfare and Benefits. As well as also writing extensively on these issues, David explores other areas relating to society and culture, evangelical christianity (of which he is a believer) and criminal justice. David’s blog can be read at www.thoughtsofbinder.wordpress.com.

love, peace and unity among us can do the best welfare for any society

For those who are interested, the following papers cite the influence of the media and social media in shaping public perceptions around welfare and those in receipt of benefits (i.e. the poor.) Note however that the assertion that the influence of the media has increased in the past 30 years is my opinion only.

http://drum.lib.umd.edu/bitstream/1903/10105/1/Yarborough,%20Connie.pdf

http://www.jrf.org.uk/system/files/2224-poverty-media-opinion.pdf

http://shiftingattitudes.pbworks.com/f/Media+Images+of+the+Poor.pdf

http://www.nieman.harvard.edu/reportsitem.aspx?id=102223

http://sm-and-s.org/uploads/2012/10/Social-Media-and-Public-Opinion-Lucas-Braun-2012.pdf