Ben Worthy and Cat Morgan offer some thoughts on the role of data in the second jobs scandal and the potential for change in the light of recent developments.

The ‘second jobs’ scandal, triggered by developments around Owen Paterson’s lobbying activities, has been a data driven scandal: it has shown how data sometimes brings about accountability but can equally provoke resistance, behaviour change or trigger more monitoring – sometimes all at once.

The actual exposure of Paterson’s rule breach began back in 2019 when the Guardian submitted a Freedom of Information request on his lobbying on behalf of two companies. This resulted in an investigation by the Standards Commissioner, which concluded there had been breaches of the MPs’ Code of Conduct. There was then a final report from the Committee on Standards. So far, so normal. There was disclosure, data, and then, slowly, the accountability system began to move.

It was at this point things got a little less normal. It is often presumed, or hoped, that information about wrongdoing leads to sanctions. Yet our Leverhulme study looking at who is Monitoring Parliament has shown that exposure can equally provoke resistance. In the case of Paterson, in very much a change to the usual nodding through of a sanction, Conservative MPs were whipped to vote against punishing him and in favour of reforming the entire appeal system. Some voted in favour, though many abstained and a few rebelled. Exactly what drove the concern is unclear, but the resistance backfired, in what is informally known as the Streisand effect, where attempts to hide something draw attention to it instead. Amid a wave of criticism and non-cooperation, the outcome of the vote was undone within 24 hours. But the vote was the beginning of the scandal, not the end.

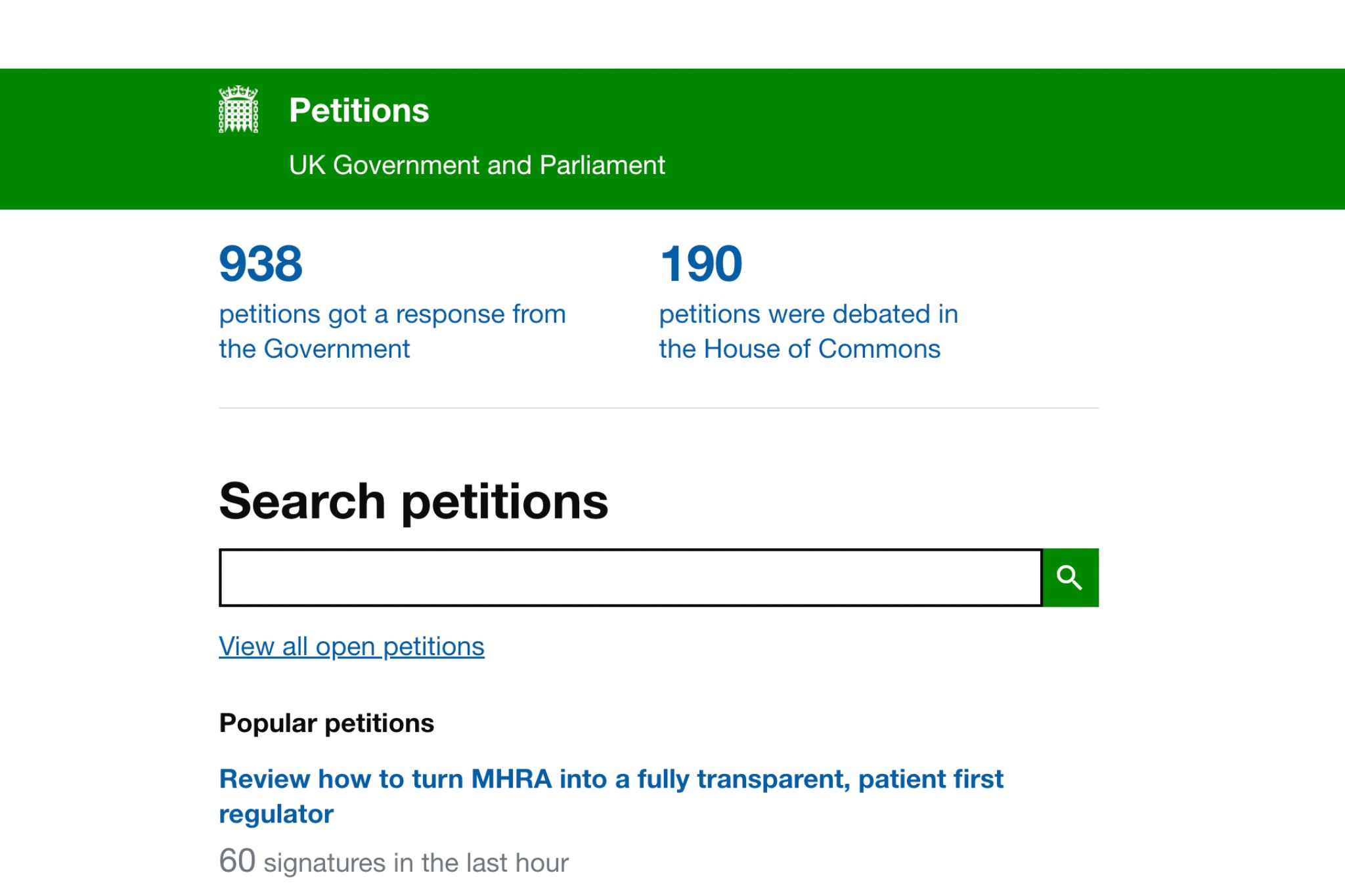

It was in the wake of the vote that journalists began really looking into MPs’ interests and incomes. The data have been, as Peter Geoghegan put it, ‘hiding in plain sight’ for many years. It is very far from perfect and rather difficult to search, as you can see here, though it can be analysed more easily here. Nevertheless, a small group of activists and journalists have always kept an eye on interests, and there has been a bubbling away of stories for as long as Registers existed, as these recent MP fossil fuel interests and Lords stories show.

After the vote, the sudden attention spike drove analyses in several directions. Initially, a few enterprising searchers found out how many MPs voting to scrap the system were either under investigation (a quarter of them) or were earning second incomes. Data crunching found that second jobs were primarily a Conservative problem (‘at least a quarter of Tory MPs have second jobs’), though it did come to cover the SNP and Labour. Data was examined from Scottish and Welsh angles, and party leaders came in for particular criticism. Johnson was criticised over his apparent hypocrisy given his own substantial earnings; Keir Starmer’s advisory work was also the subject of debate.

In parallel to the national collective picture, there was trickle down to individual MPs. The BBC, Guardian, and The Times created postcode lookups so you can see what your MP had earned. From Doncaster to Cumbria, and Belfast to North Wales, local reporters were combing through their MPs’ entries. This sort of reporting would be most worrying for MPs who can ride out a national scandal but could be in serious trouble if data became the talk of the local high street.

At this point, the data became a spreading series of stories about how and where MPs vote, how they spend their expenses, and whether they are lobbying. The most high profile was, of course, Geoffrey Cox, whose Caribbean activities kickstarted a discussion about tax havens. In its wake came Grant Schapps, who The Times claims has been ‘spending public money on lobbyists opposing the government’s own plans to build on private runways, including one he has personally used’. Attention has since turned to other data hiding in plain sight, such as the list of former MPs with Parliamentary passes or some All-Party Parliamentary Groups.

This leads to the key question we are asking, which is whether, or how, all this data and monitoring makes things change. Certainly, MPs have acted. So far, some MPs have responded by self-reporting undeclared interests or admitting possible breaches. Others have signalled their good behaviour, seeking positive headlines, such as the ‘No second job for Isle of Wight MP Bob Seely’. On the other hand, there are rumours from Conservative MPs that ending second jobs could tigger resignations.

What, if anything, will happen next is uncertain. Outside of Westminster, the public are (mostly) against second jobs. Inside the House of Commons, Labour pushed for a vote on banning second jobs and the Conservatives now seem to agree, though the devil may be very much in the detail. Data can only drive change so far. As with past scandals, we have the data, we have the outcry, but now we shall see if it turns into institutional change or fades away.

______________

Ben Worthy is a Senior Lecturer in Politics at Birkbeck, University of London.

Cat Morgan is a Research Associate at Birkbeck, University of London and PhD candidate at the University of Southampton

Photo by Matt Milton on Unsplash.

1 Comments