The massed protests against the government’s rise in tuition fees last winter illustrated that the public was willing to take to the streets -and in some cases use violence – to show their disapproval of the government’s policies. Bart Cammaerts explores how the media on both sides of the political spectrum covered these protests, and finds that while the symbolic violence of the protesters did not obscure the issues that were being protested, the internal conflicts within student groups were actually more detrimental to the reporting of the issues.

The massed protests against the government’s rise in tuition fees last winter illustrated that the public was willing to take to the streets -and in some cases use violence – to show their disapproval of the government’s policies. Bart Cammaerts explores how the media on both sides of the political spectrum covered these protests, and finds that while the symbolic violence of the protesters did not obscure the issues that were being protested, the internal conflicts within student groups were actually more detrimental to the reporting of the issues.

The liberal media tend to react negatively against any form of political violence, which is often denoted as anti-democratic and illegitimate. It is well documented that the large majority of mainstream media outlets tend to side with the interests of the economic and political elites by whom they are owned. In addition, the mainstream media have a tendency to differentiate between a peaceful majority and a violent minority and to focus on the symbolic violence rather than the causes of the violence.

Despite this, not all mainstream media are at all times docile actors in the service of state and/or capitalist interests, and it would be wrong to depict the entirety of mainstream media as outright opposed to social movements, citizen and public interests. A content analysis of recent articles relating to the student protests and the tuition fee debate published in a variety of newspapers suggests that a more intricate perspective emerges in the reporting of protest and of violence.

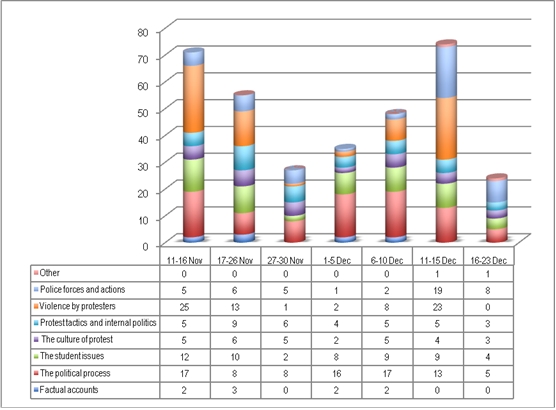

Figure 1: Shifts in main focus of the articles across time (N-Values)

Source: own data (N=334)

As Figure 1 illustrates, there is fluctuation over time in the amount of media attention on the tuition fee debate and the student protests. The peaks in media attention for the protest and the political debate regarding tuition fees coincided with the various demonstrations; the first demo with the Milbank incident (10 November) and the fourth turbulent demo at the time of the vote (9 December), considerably increased the total number of articles devoted to the protests and the tuition fee debate.

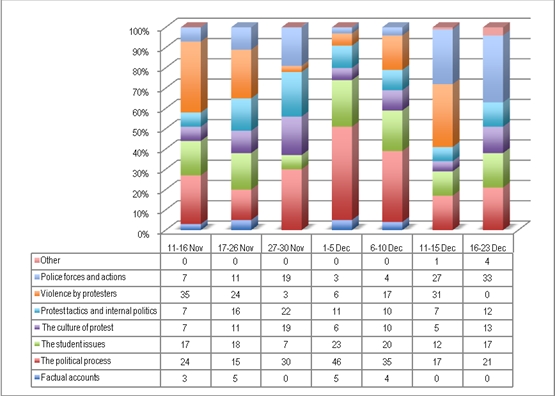

Figure 2: Shifts in main focus of the articles across time (Percentage)

Source: own data (N=334)

As Figure 2 shows, the increase in attention for violence by protesters did not dramatically affect the amount of attention for the issues the students wanted to address. In fact, internal politics and conflicts within the movement did much more damage to the reporting on the issues than violence did as the period 27-30 November 2010 shows. After the vote in Parliament and the contentious encounter with the royals we can also observe a slight drop in attention for the issues students wanted to address as only 12 per cent of articles related to student issues in the period 11-15 December compared to an average of 16 per cent for all articles. Another relevant point is that in the latter period of the analysis attention for the actions of police and police violence increased dramatically.

Looking at the number of words attributed to sources, Table 1 shows that on average quotes of politicians take up 17 per cent of a news article in the Daily Mail, compared respectively to 14 per cent in the Daily Telegraph, 16 per cent in the Guardian and 16 per cent in the Independent.

Table 1: The average per cent of article space taken up by sources when quoted and number of news articles in which sources are quoted

| Daily Mail | Daily Telegraph | Guardian | Independent | |

| Politicians | 17 per cent | 14 per cent | 16 per cent | 16 per cent |

| Police | 13 per cent | 14 per cent | 12 per cent | 11 per cent |

| Experts and Witnesses | 11 per cent | 11 per cent | 10 per cent | 11 per cent |

| Moderate Student Protesters | 8 per cent | 9 per cent | 15 per cent | 11 per cent |

| Militant Student Protesters | 17 per cent | 19 per cent | 17 per cent | 13 per cent |

| Non-Student Civil Society | 20 per cent* | 14 per cent | 18 per cent | 7 per cent |

* This figure should be disregarded as it concerns only one article, an interview with a labour union leader

Source: own data

This analysis exposes that while there might be more official sources used in total, the amount of space they occupy in quotes is on average fairly similar to that of (militant) students. There are not only more militant student sources given a voice, but on average they are being given more space than moderate student voices across all publications.

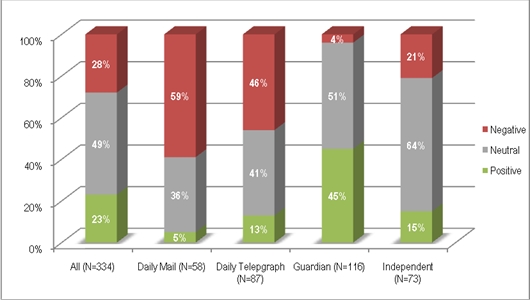

Figure 3: Overall tone of the articles towards student protesters

Source: own data

Figure 3 shows that the rightwing press was often very negative towards the students and the protests. Despite this, in some of the rightwing press articles student protesters were being represented positively, usually in conjunction with making a distinction between ‘good’ moderate and ‘bad’ radical students or through interviews with labour union leaders praising the students for their protest actions. The Daily Mail as well as the Daily Telegraph even supported to some extent the cause of the protesters, but were highly disapproving of the tactics used by the more militant protesters:

this wasn’t a typical protest. For a start, these students have a legitimate grievance, as it is about to become very much more expensive for middle-class Britons to get an often poor quality university education. (Daily Mail, 11/11/2010)

without condoning the violence, we should be mindful of the deep sense of grievance among today’s youth – the widespread feeling that they have a raw deal. This generational inequity is most starkly exemplified by the imposition of student fees by people whose own university education was lavishly subsidised. (Daily Telegraph, 11/12/2010)

The frame in which the violence of protesters (not of police) was positioned nevertheless reveals the ideological differences between the rightwing and leftwing press:

- A neutral frame implies that both positive and negative voices are given space in the same article.

- A negative frame represents the typical liberal response, describing the violence of protesters in a condemning way, as illegitimate, orchestrated and unworthy of a democracy.

- A positive frame on the contrary approaches the violence as legitimate resistance, passionate politics, and necessary to get heard or as banter and teenage naughtiness.

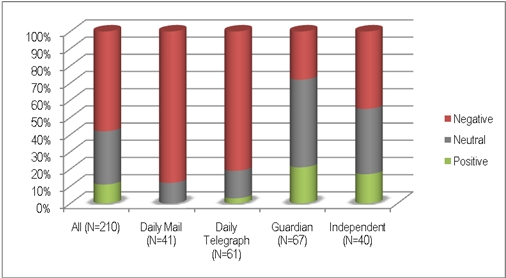

Figure 4: Frames towards violence

Source: own data

The dominant frame towards the violence of student protesters was a negative one (Figure 4), but while the rightwing press almost unequivocally condemned the student violence, the leftwing press took a much more nuanced and neutral stance, at times even adopting a positive frame towards the violence of protesters.

A common tactic of the establishment is to construct a division between a peaceful legitimate majority and a violent minority that hijacks the demonstration to cause disruption and mayhem. Some students tried to refute those claims:

I hate the way they try and blame it on a small minority, everyone here is angry – it’s not a small group of hardcore anarchists, it’s just students who are very, very angry. (Student protester quoted in BBC, 2010)

33 per cent of articles differentiated between moderate and radical student protesters and of those articles more than 3/4 represented the moderate and the militant groups as separate groups with distinct agendas, implying that radical groups who are not students hijacked the student demonstrations to cause massive disruption and violent disturbances. This perspective was not only prevalent in the rightwing media, but also in the leftwing:

Observers said as few as half of the crowd were students, with a rent-a-mob of anarchists and other thugs taking control. (Daily Mail, 10/12/2010)

There are fears that anarchist groups and violent yobs are planning to hijack the protests and “shut down” the capital. (Daily Telegraph, 9/12/2010)

it is about the Lib Dem leader that the protesters, the peaceful majority and the anarchic minority alike, are most venomous. (The Observer, 5/12/2010)

Some blamed non-students, including teenage gangs and anarchists, who, they said, infiltrated the protests, intent on crime and disorder. (The Independent, 12/12/2010)

More nuanced positions – for example outlining that moderate and radical groups have the same goals but are just using different protest tactics or giving voice to those that challenge this distinction fundamentally – as the student quoted above does – were less prevalent, especially in the rightwing media.

The type of symbolic violence enacted by the student protesters considerably increased media exposure for the students and their cause. The symbolic violence did not necessarily impede attention for the issues protesters wanted to address; the internal conflicts were deemed more detrimental. Furthermore, militant voices were more numerous and received more article space on average than moderate voices. However, getting attention does not necessarily mean positive exposure, but neither does it mean exclusive negative exposure.

While there was some degree of understanding for the passion and anger of the students towards the government in the rightwing media, the use of violence led to an overall condemnation, often linked to a negative representation of the spoilt middle-classes.

All in all these results suggest that we should be more careful in assessing the use of symbolic violence by protesters; although there are clearly problematic issues with the use of violence in a democracy, symbolic violence is not necessarily as detrimental to a given cause as is often claimed in terms of generation media exposure. The shock effect of violence produces considerably more publicity and it demonstrates the seriousness of the situation and the resolve of the resistance. However, violent tactics, even if they are mostly symbolic in nature, also lead to fragmentation and internal conflicts, which the media exploit and amplify.

Please read our comments policy before posting

1 Comments