Emily St.Denny, Andrew Connell, and Steve Martin analyse two contrasting attempts by the Welsh Government to develop and deliver distinctive subnational policies. They demonstrate the importance of looking beyond formal institutional powers and of paying attention to policymakers’ political skills and visibility, as well as to the strategies and tactics that they employ in deploying formal powers.

Emily St.Denny, Andrew Connell, and Steve Martin analyse two contrasting attempts by the Welsh Government to develop and deliver distinctive subnational policies. They demonstrate the importance of looking beyond formal institutional powers and of paying attention to policymakers’ political skills and visibility, as well as to the strategies and tactics that they employ in deploying formal powers.

There are many reasons why powers are devolved to subnational governments, not least of all the argument that bringing decision-making closer to communities allows for choosing policies that better suit their specific needs and interests. Developing and delivering distinctive policy is therefore a central claim for advocates of devolution. In the UK, for instance, devolution to Wales and Scotland was supposed to yield, in the words of Wales’ inaugural First Minister Rhodri Morgan, a ‘living laboratory’ for developing ‘different approaches to common problems’. The ability of devolved governments to make good on this promise is nevertheless tightly circumscribed by the powers and resources at their disposal, many of which are settled in the formal agreements that set out their competences. However, our research suggests that devolved governments may have a wider range of policy and governance resources at their disposal to develop and deliver distinctive policy agendas than might be assumed, but that wielding these to get their way is not always straightforward.

Rules, capacities, and legitimacy

The decentralisation of powers from national to subnational governments is often intended to respond to demands for greater recognition of regional and local identities within larger states, and to the perception that ‘one-size-fits-all’ policy is not always an appropriate way to make policy. The question of how subnational governments successfully make and deliver distinctive policy is therefore central to our understanding of effective policymaking and implementation in increasingly multi-level governance systems.

Claims of distinctiveness can be made of both the policy output (i.e. what decisions are made) and the decision-making process (i.e. how decisions are made). In the first case, the areas the government is legally competent to make decisions in are limited to those authorised by the state in the decentralisation agreement. In the second case, the process by which these decisions are made is primarily governed by the operating procedures of the devolved institutions (e.g. parliament or assembly) set up for this purpose. Together, these legal and institutional frameworks are generally considered to determine the limits of a devolved government’s ability to make and deliver distinctive policy.

In reality, this story is a little too simple. The ability of subnational governments to act as they wish is not just governed by these rules and by questions of material and institutional capacity. Instead, how subnational governments choose to deploy the formal powers and other resources available to them, the circumstances in which they do so, and their perceived legitimacy to act on the issue, all matter a lot for their ability to develop and successfully implement distinctive policy agenda.

Wales as a case study in subnational policymaking

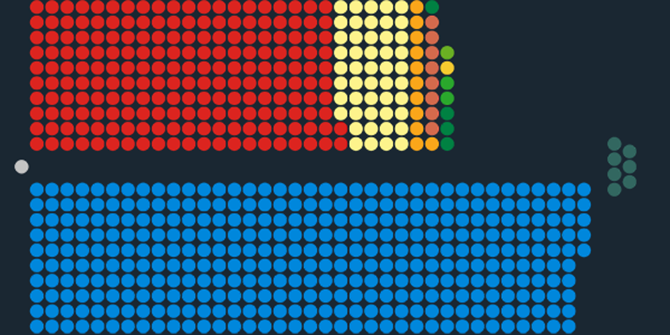

We focused on the Welsh Government as a way of exploring the question of effective subnational governance in greater detail. In 1998, responsibility for key areas of domestic policy (notably, education, health, social care and housing, as well as some aspects of skills, agriculture and transport policy, but not the criminal justice system or welfare policy) was formally transferred from the Welsh Office, a department of the UK government, to an elected National Assembly for Wales (now Senedd Cymru). Since then, there have been instances where the Welsh Government has been able to create and implement policy that diverges from that of the UK Government, and others where it has struggled to do so.

The case of homelessness policy reform is an example of successful policy divergence. Indeed, in 2014, Wales became the first nation in the UK to introduce a statutory duty on local authorities to prevent (rather than just react to) homelessness. While passing this law may seem straightforward – this was, after all, a policy area over which the Senedd had legal competence – it actually involved the intensive fostering of networks among devolved and local policymakers, service providers, and third sector actors. Without this strong network, the Welsh Government’s very small Homelessness Policy Team might have struggled to develop the policy and to support local authorities with implementation. The effectiveness of these networks partly came down to the Welsh Government’s perceived legitimacy and political capital on this issue: the unambiguously devolved nature of homelessness and housing, coupled with Welsh Government’s collaborative leadership, incentivised and encouraged key players across sectors to work together to develop and deliver this distinctive policy.

Conversely, the difficulties faced by the Welsh Government to introduce Minimum Unit Pricing (MUP) regulation for alcohol reveals what happens when the legitimacy and authority of subnational governments to make policy on an issue are challenged. Seeking to follow in the footsteps of the Scottish Government, which had passed a law introducing MUP in 2012, the Welsh Government introduced a provision for MUP in its wide ranging Public Health (Wales) Bill 2014. A combination of factors significantly complicated the measure’s adoption, including the ongoing legal challenges to the Scottish law from industry bodies (also at the EU level); the ambiguous nature of the policy as pertaining to either public health (devolved) or criminal justice (reserved to the UK Government); intensive industry lobbying to have the Welsh Government considered not legally competent on this issue; and UK Government preference for voluntary ‘Responsibility Deals’ with industry rather than binding regulations. As a result, the measure was removed from the Public Health Bill, then tabled separately in 2015, before being abandoned and only reintroduced again in 2017 at around the same time as the Scottish Act was declared lawful by the UK Supreme Court. The Public Health (Minimum Price for Alcohol) (Wales) Act was passed in 2018 and entered into force in 2020.

In the case of MUP, then, ambiguity over the Senedd’s legal competence and legitimacy, as well as the Welsh Government’s decision not to dedicate its limited resources to fighting lengthy legal battles against industry lobbies, all contributed to a more protracted path to delivering its policy preferences.

Conclusion

Our findings matter for both scholars who study subnational and multi-level policymaking and policy practitioners. It suggests that we need to look beyond the formal rules and material capacities of subnational governments in order to understand how they govern, and to consider the broader social and political context in which they are trying to make and deliver policy.

Seen this way, success also becomes contingent on which issues are being pursued, at what time, and with whose support or opposition. In particular, the positioning of subnational governments between the local and the state levels may grant them a pivotal position in policy networks and permit valuable opportunities for collaboration with a wide range of actors with complementary resources to help get things done. On the other hand, if they are unable to secure collaboration, or at least acceptance of their legitimacy, from influential actors, they may find themselves under pressure as those actors seek allies at other levels of government.

____________________

About the Authors

Emily St.Denny is Assistant Professor at the University of Copenhagen.

Emily St.Denny is Assistant Professor at the University of Copenhagen.

Andrew Connell is Research Associate at the Wales Centre for Public Policy.

Andrew Connell is Research Associate at the Wales Centre for Public Policy.

Steve Martin is the Director of the Wales Centre for Public Policy and Professor of Public Policy and Management at Cardiff University.

Steve Martin is the Director of the Wales Centre for Public Policy and Professor of Public Policy and Management at Cardiff University.

Photo by Catrin Ellis on Unsplash.