Seb Bytyci  argues that the ability to raise taxes is essential for transforming developing countries. Increased revenue from taxation and effective tax-collection would free developing countries from aid dependence. Evidence also suggests a correlation between direct taxation and higher life expectancy. If rich countries wish to promote economic developement in developing nations, they should help them build up industries other than agriculture and raw materials that would create better sources of tax revenues.

argues that the ability to raise taxes is essential for transforming developing countries. Increased revenue from taxation and effective tax-collection would free developing countries from aid dependence. Evidence also suggests a correlation between direct taxation and higher life expectancy. If rich countries wish to promote economic developement in developing nations, they should help them build up industries other than agriculture and raw materials that would create better sources of tax revenues.

The only things you cannot escape are death and taxes, goes the modern proverb. Having to pay taxes is probably the ultimate first world problem. It is a true first world problem in the sense that few people in the third world face it, and it is an inconvenience which is directly related to the high standard of living of the person being subjected to it. So, viewed from this perspective, the proverbial taxman is our best friend and does not enjoy the company of hooded skeletons brandishing scythes. Fortunately, recently more attention has been paid to the importance of taxation in the “third world”, including the OECD Task Force on Taxes and Development and the Tax Inspectors Without Borders project. The British government has committed itself to work with the G8 to tackle global tax avoidance. British aid has also focused on tax collection, especially in Ethiopia with some positive results.

Building effective tax collection authorities as part of a professional public administration is crucial for transforming countries, and increased revenue from taxation is essential to freeing developing countries from aid dependence. Provision of public services by accountable governments funded by local revenue is the desired goal, and taxation is the nexus where governance, economic growth and civil society meet. Therefore, the recent steps to improve tax collection are in the right direction. However, they do not go far enough. The current focus is on improving taxation of Multi-National Corporations (MNCs) and trade activities. This is seen as a way to increase tax revenue in developing countries, but this focus is misplaced; an increase of tax revenue is not necessarily going to lead to development. Moreover, indirect taxation, which in developing countries usually takes the form of customs taxes, is a feature of underdevelopment, so more effective indirect tax collection may actually make matters worse. What transforming countries need is a wider tax base and more effective collection of direct taxes.

Let’s look first at the MNCs. There is an on-going debate on whether MNCs are good or bad for development, especially in resource-rich countries. The current initiatives aim to fix some of the problems with MNCs such as transfer pricing. But, the reality is that even if all MNC activities are taxed fully that would not fix the problem of low revenues let alone underdevelopment. MNC investment remains small in developing countries. For instance, one fifth of all Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in the developing countries in the 2000s went to China, but it constituted only about 2.5% of China’s GDP. On the other hand, in Ethiopia for example, which has had special attention from DFID, FDI inflows were 0.97% of GDP in 2010. The majority of FDI goes to rich countries and the large economies.

Taxman vs. Grim Reaper

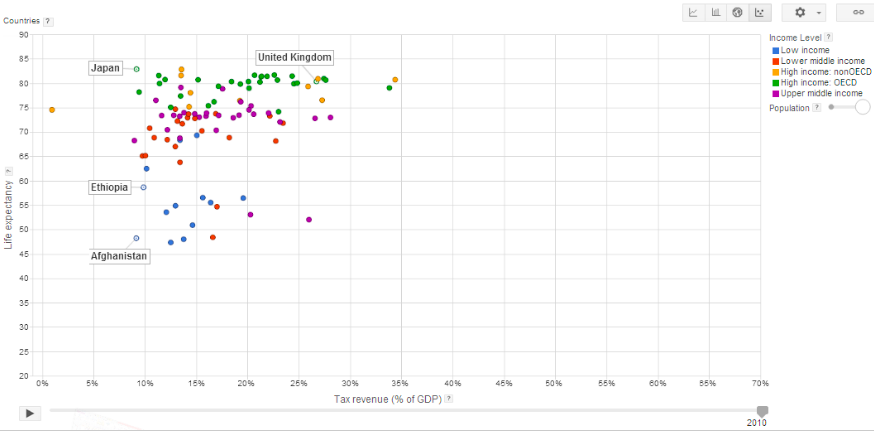

Now let us go back to the relationship between taxes and death. Looking at the World Bank Development Indicators (through the Google Public Data module), we can see the link between taxes and life expectancy. The graph below shoes the relationship between Tax revenue as percentage of GDP and Life expectancy. There is no discernible pattern here. Afghanistan (with one of the lowest Life expectancies in the world) and Japan (with the highest Life expectancy) have a similar percentage. Whereas, Ethiopia and United Kingdom have both different levels of tax collection and life expectancy.

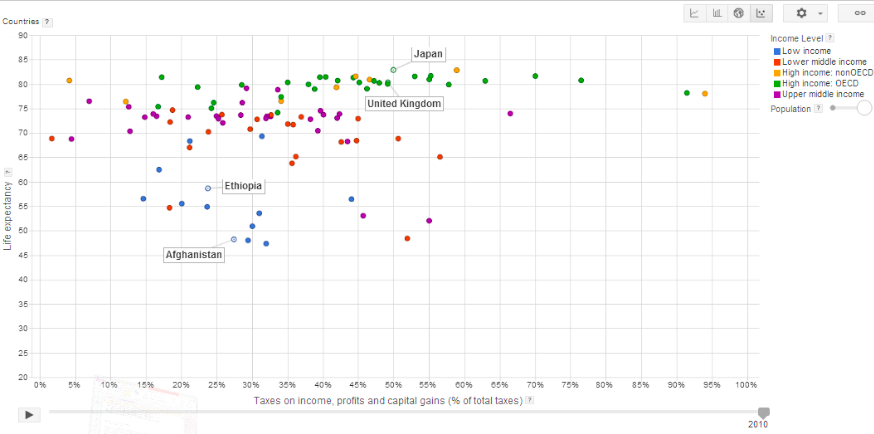

So, there is no relationship between tax collection expressed as percentage of GDP and life expectancy. However, if we look at what type of taxes a country collects we can find how tax collection is related to life expectancy. And, the main difference, as you might expect, is between direct and indirect taxes. Let us see what is the relationship between the level of direct taxation as a percentage of total taxes and life expectancy in the graph below.

Here we can see a discernible pattern. Notice how the dots form a shape facing upwards and rightwards. Here we can claim a correlation between direct taxation and higher life expectancy. You can see how poor countries (in blue), such as Afghanistan and Ethiopia are at opposite ends of the shape compared to the rich countries (in green), such as Japan and UK. This is not a claim of causation, the level of direct taxation is itself an outcome of a plethora of policies aimed at increasing the internal tax base, such as industrial policy, that a government undertakes.

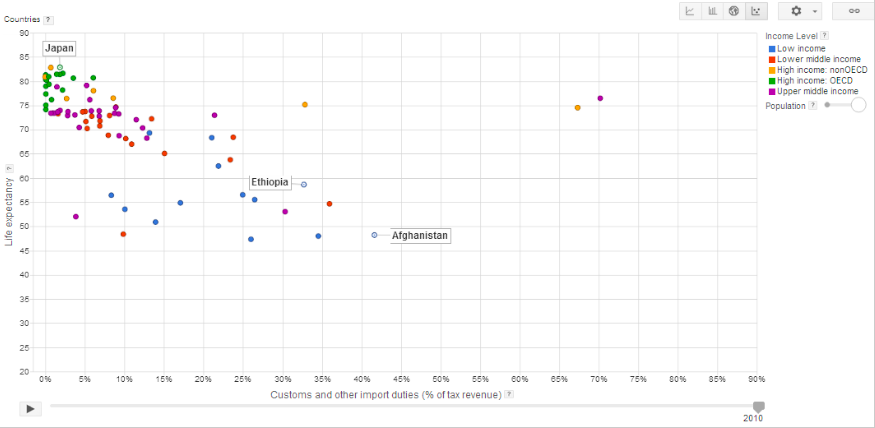

For this to make sense fully, something else must be shown to be true. That is, there must be a discernible (negative) relationship between external trade related – indirect – taxes (i.e. customs) and life expectancy. Let us see if that is the case in the graph below which looks at the interplay between Customs and other import duties as percentage of total tax revenue and Life expectancy.

Here we see a shape facing in the opposite direction of the previous one, indicating a negative relationship between the level of customs taxation and Life expectancy. Notice how, again, the poor countries are at the opposite end to the rich countries. If a country relies on customs taxes to fill its coffers it is in severe trouble. You can click the link here and see how this relationship evolves over time.

Follow the money

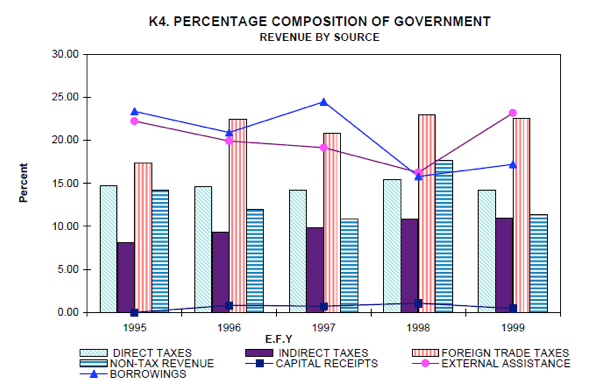

Let us look at the revenue structure of a poor country, Ethiopia, and compare it with that of a rich country, UK. Below is a graph representing the breakdown of government revenue in Ethiopia over the period 1995-1999. (Source: Ethiopian Ministry of Finance and Economic Development).

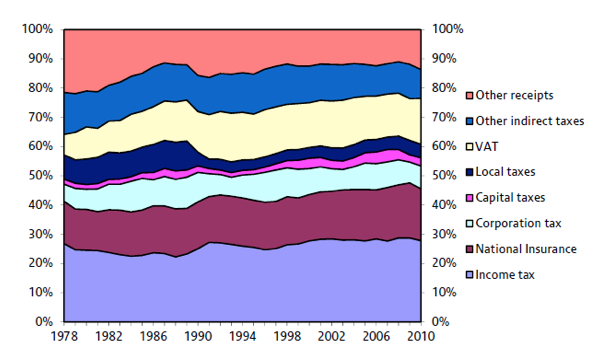

As you can see, direct taxes make up a small amount of tax revenue (around 15%). A poor country such as Ethiopia relies on customs and foreign aid to fill its coffers. Now let us look at the government revenue breakdown in the UK. (Source: Institute for Fiscal Studies).

As you can see, Income tax, and National Insurance tax (two direct taxes), make up nearly half of all receipts. Income tax is the single most important one, and it makes up over a quarter (26.2% in 2012-2013) of total receipts. Compare that with Ethiopia where income tax makes up only 4.31% of total revenue (in 2008/2009).

Why is this the case and why don’t rich countries help poor countries increase direct taxation?

Because poor countries do not have a strong industry, they have less employed people to tax. So they rely on aid and customs (taxing imports) to fund public services. This leads to massive trade imbalances (see graph below), which can only be supported with remittances from their diasporas in rich countries. (Yes, immigration has something to do with development). As they have weak industries, poor countries must specialize on selling agricultural products and raw materials which have lower value than manufactured products. This becomes a cycle of low exports, weak industry, low revenues, low investments, poverty and migration. Some scholars, such as Ha-Joon Chang, say that rich countries are kicking away the ladder after they have achieved prosperity, and even when they help they are being bad Samaritans by focusing on the wrong priorities (i.e free trade) and not allowing poor countries to build their industries.

How not to build an economy

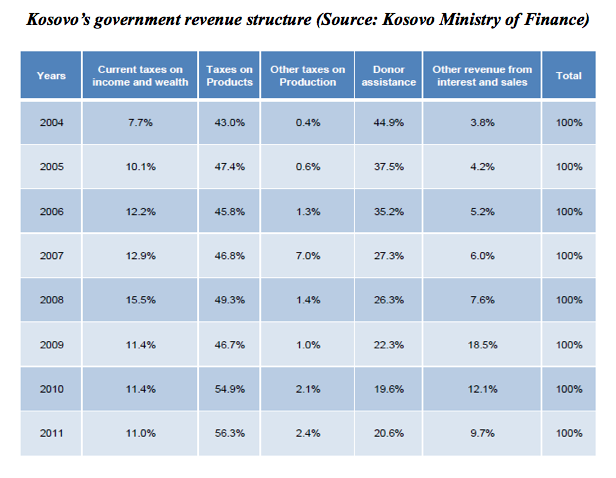

We can look at an example where rich countries were directly responsible for state-building and economic development. This is Kosovo where the European Union (EU) as part of the UN Administration (UNMIK) was in charge of the economy after the war in 1999. Unfortunately the result there is not positive. The tax revenue structure looks similar to that of other poor countries, with overreliance on customs (see graph below). There is a massive and growing trade gap, little industry, very high unemployment and a high level of migration to the EU.

As the donor countries were trying to decrease their assistance to Kosovo, they focused on customs taxes as a replacement. In the above table you can compare the third and fifth columns (labelled “Taxes on products” and “Donor assistance”) to see how as donations decreased, indirect taxation increased, with direct taxation (in the second column) remaining very low. This makes sense only if we presume that promotion of free trade, instead of local industry, was seen as desirable and customs tax was an easy identifiable target to replace donor assistance.

So what?

There is a need to focus on the right priorities for poor countries. Trade policy is development policy, and if poor countries are forced to specialize in agriculture and raw materials they are being banished to underdevelopment and poverty. From this discussion we are left with a few important questions for the future of developing countries. With the donor countries under pressure to cut aid to poor countries, are we seeing efforts to use customs taxation to replace aid? If the structure of the economies of poor countries does not change, will the decrease in aid, which serves as a band-aid for poverty, lead to more misery for poor countries? Will the improved capacity of customs tax collection make poor countries complacent in thinking that they have a solution to poverty and prevent them from designing growth strategies?

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the author

Seb Bytyci is a doctoral researcher at the University of York, researching the public sector in transforming societies, with a particular interest in the UK and EU aid and foreign policy. His background is in public policy and political science. He blogs sometimes on matters related to his research at statesoftransformation.quora.com and tweets at @bytyci.

You can see our suggestion for how to cite our articles here: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/how-to-cite-our-articles

Please how can i reference this article on my referencing list? thank you

Thanks for your comments Arianit. The Kosovo Customs service is very effective and efficient. Elton Skendaj (http://pir.fiu.edu/people/faculty/elton-skendaj/) has researched it for his PhD, and documented the extensive training that officers received.

I was doing research with small and medium enterprises in Kosovo, ten years ago, and they were complaining about the customs tax levied on imported raw materials and machinery. Astonishingly, this is still the case in Kosovo.

Your post is spot on regarding the need to focus on direct taxation and how that leads to more accountability.

Excellent! I have heard Kosovo Customs director specifically state that customs were seen as a critical point for the funding of Kosovo’s budget and in return recieved the utmost administrative attention. Kosovo Customs, as opposed to most other sectors of government in UNMIK’s Kosovo, was exclusively a British venture, with the effectiveness to show. In the downside, the effort to extract every single cent via customs meant that there was never a development or industrial policy in place as production resources were taxed at the same rate as finished products. I would also look at the accountability that dirrect taxation produces in a society and regressive effect that customs and other flat taxes have on the poor. I have blogged (in Albanian) the negative effect that nickel and diming tariffs in return for social services have, which has also been enouraged during UNMIK in order to build sustaniable public services. https://arianit2.wordpress.com/2011/04/13/ma-pak-tarifa-ma-shume-taksa/