Tax cuts during a pre-election Budget make party-political sense. They ensure some electoral support and create constraints that a new government will find hard to overturn. Tony Blair and Gordon Brown faced a similar predicament during their first term in government. But the economic and geopolitical situation in 2024 is much worse than in 1997, warns Tony Hockley.

A pre-election Budget always brings a change of priorities, putting short-term popularity ahead of long-term concerns. The 2024 Budget will be remembered as one of the worst of its kind. Playing the usual political games, the Chancellor has effectively locked a future government into disastrous spending plans alongside a flat-lined economy. The Budget has, knowingly, made a bad situation worse. A new government would need to play a very long game to turn this situation around.

In 2024 health and social care are, like most public services, in a catastrophic state. They are struggling with workforce shortages, made worse by arbitrary and fluctuating rules of migration, and picking up the pieces from the collapse of local authority social services. Furthermore, for all the promises to “fix social care”, to “focus on prevention”, and “learn the lessons from the pandemic” these systems are failing. Just as happened with John Major’s “Citizen’s Charter” it is now only the measured outcomes that matter. Reducing the hospital waiting list, by any means, is almost the sole focus of health policy. The demise of social care and the UK’s awful record on cancer have been deprioritised ahead of the general election. The promised initiative on “health disparities” has been firmly dropped, even though dramatic health inequalities were perhaps the UK’s greatest weakness in pandemic preparedness. The volatility of conservative thinking has seen a strategy to tackle health disparities replaced by a mission to remove funding for equity, diversity and inclusion.

Given the circumstances of 2024, the Budget focus on pre-election tax cuts is deeply dangerous when the need for spending on health and other public services, particularly local authority social services, is so obvious and urgent.

Given the circumstances of 2024, the Budget focus on pre-election tax cuts is deeply dangerous when the need for spending on health and other public services, particularly local authority social services, is so obvious and urgent. Instead, the Chancellor used the Budget to reaffirm his commitment to public service funding, increasing it by a mere 1% a year. The Budget will make the predicament of public services much worse. Demands for public sector efficiencies are the conservative equivalent of the “magic money tree”. In the Budget he promised funding to make the NHS a “digitally integrated” system (with no reflection on his failed promise as health secretary to achieve a “paperless NHS” by 2018).

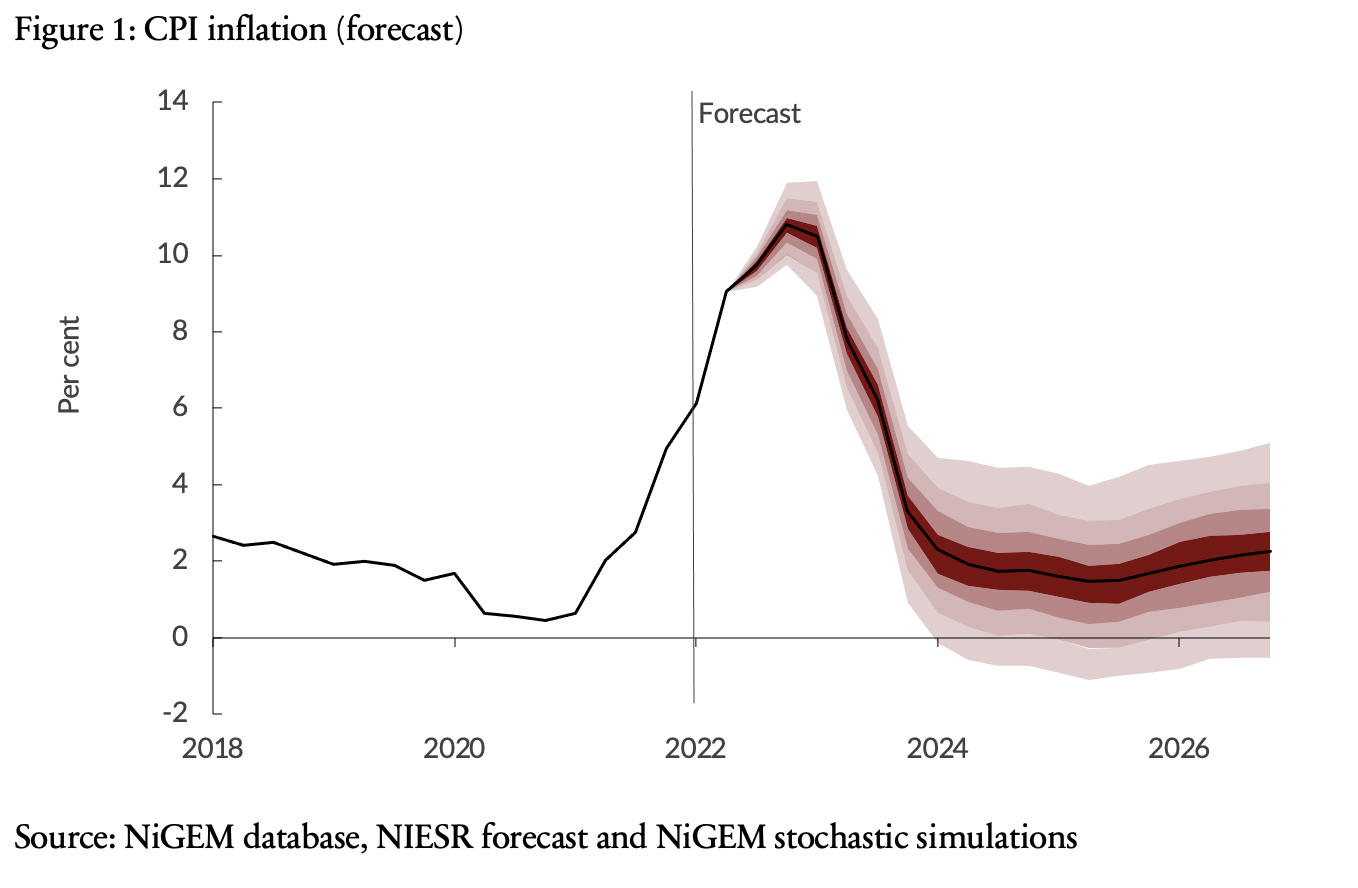

There is nothing efficient about leaving unmet need in health and social care. Nor is there anything efficient if businesses have to work around crumbling infrastructure and social systems: Britain’s productivity problem is the result of sustained under-investment in infrastructure. Many will recall health secretary Matt Hancock declaring in 2018 that “prevention is better than cure”. Efficiency is made far worse by pre-election tax cuts, as Nigel Lawson demonstrated with his 1987 budget announcing a 2p cut in income tax and stoking post-election inflation.

Blair and Brown fell for that trap, committing to match the Conservatives’ austerity plans of the November 1996 Budget during their first two years in power, and not to raise income tax rates.

Using the pre-election Budget to sustain a core vote that might prevent complete political collapse, while at the same time setting a trap for the Labour party may make some party-political sense. This was certainly the case in 1997 and, as Esther Webber has recorded, in many previous elections. John Major’s ailing government was determined to portray Tony Blair’s “New Labour” as the “same old tax-and-spend” party, much like Jeremy Hunt did in his speech today. Blair and Brown fell for that trap, committing to match the Conservatives’ austerity plans of the November 1996 Budget during their first two years in power, and not to raise income tax rates. Labour, surprisingly, stuck to these damaging commitments, keeping health spending growth as low as 2.2% until 1999. By the time of the 2001 general election, the strain in the health service was showing.

It will be a tough challenge, given these circumstances, for a potential Labour government to give hope that “things can only get better”.

But the economic and geo-political circumstances were very different in 1997. The same focus on party politics alone is inexcusable in 2024. Britain has never been this vulnerable in modern times and the need to restore trust in politics should be a priority. Yet it is hard to see a positive end to the game being played by the Government. People do not vote for “tax and spend”. The only popular taxes are those imposed on “other people”, but the only ones that really raise core spending are taxes imposed on everyone. The Chancellor’s choice of another 2 per cent cut in the National Insurance might help fill a minority of the workplace vacancies (along with increasing working hours). But the cut is forecast to increase total hours worked by just 0.3 per cent, and do nothing to address the underlying challenge of economic inactivity within the working age population.

People understand that Britain’s problems are now very deep, after the imposition of an “austerity” strategy in 2010, followed by the pandemic and global geopolitical instability. But a budget with a vision as short as a few months shows no sign of this understanding. The tax burden and the volatility of market confidence in UK governance at the end of a bizarre parliament leave little room for bold initiatives by a new government. The Chancellor could only assert that tax cuts would solve Britain’s problems, defying expert analysis, saying on tax cuts and economic growth: “economists argue about cause and correlation, but we know …”.

It will be a tough challenge, given these circumstances, for a potential Labour government to give hope that “things can only get better”. It was a credible claim in 1997, but the 2024 Budget has made such hope a little more distant.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: ITS on Shutterstock