Between 2010 and 2015, the Green Party went from being an

Between 2010 and 2015, the Green Party went from being an  afterthought in British politics to an established member of the second tier of Britain’s party system. Although their 2015 election result disappointed many, the “Green Surge“ in membership from late 2014 onwards turned them into the third largest party in England and Wales. Monica Poletti and James Dennison explain the surge did not alter the party’s ideological composition but instead reinforced earlier movements to the left. The Green Surge also created a more balanced membership profile in terms of gender, education and social class. But while most of the party’s members voted for the Greens, one in five of these “surgers” did not, raising questions as to the durability of their membership.

afterthought in British politics to an established member of the second tier of Britain’s party system. Although their 2015 election result disappointed many, the “Green Surge“ in membership from late 2014 onwards turned them into the third largest party in England and Wales. Monica Poletti and James Dennison explain the surge did not alter the party’s ideological composition but instead reinforced earlier movements to the left. The Green Surge also created a more balanced membership profile in terms of gender, education and social class. But while most of the party’s members voted for the Greens, one in five of these “surgers” did not, raising questions as to the durability of their membership.

In just seven months, between October 2014 and May 2015, the Green Party’s membership increased from less than 20,000 to over 60,000. The growth is interesting not only because membership figures of all British parties had until then been in decline for decades, but also because a near overnight trebling of any party’s membership would be expected to radically change the profile of its average member. Indeed, many commentators spoke at the time of a shift in the Greens from an environmentalist stance to a leftist or even populist positioning.

Here, we explore if and how the Green Party’s membership was transformed by the Green Surge using data from the ESRC Party Members Project (PMP). Based on 845 Green members surveyed shortly after the 2015 general election, we divide these into three cohorts based on date of joining: before 2010 (12 per cent of those surveyed), between 2010-2013 (15 per cent) and the Green Surge period of 2014-2015 (73 per cent).

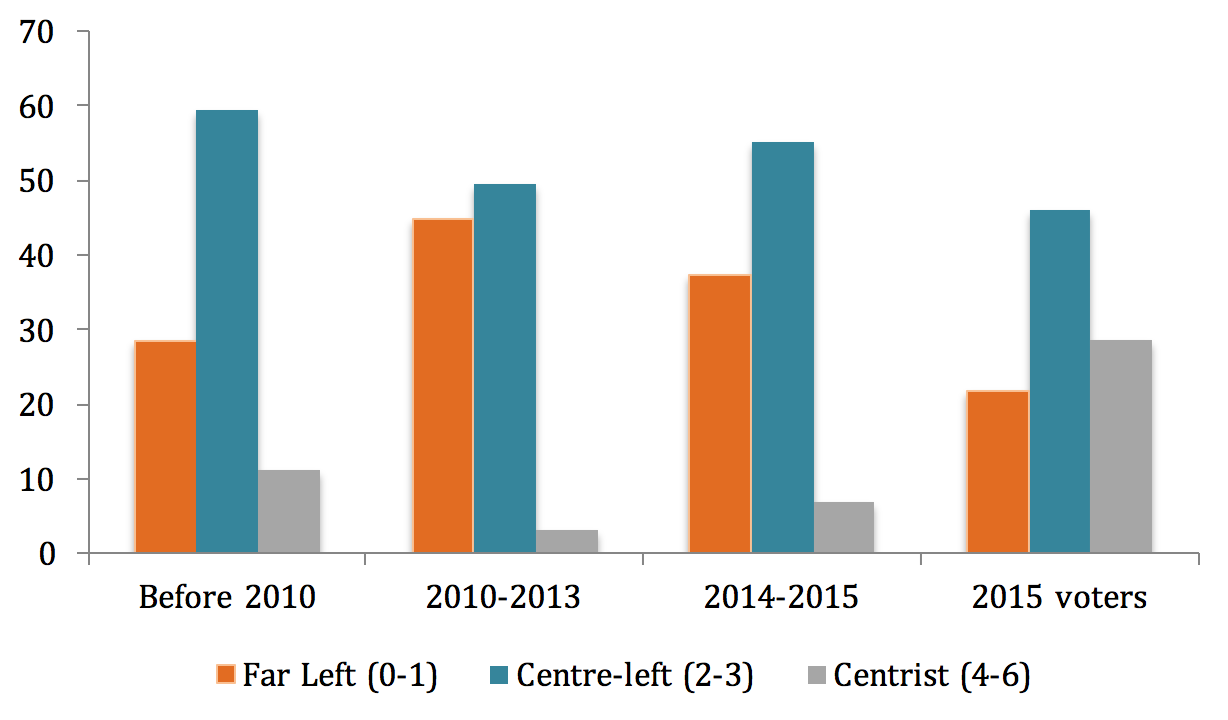

First, we look at left-right self-placement. Green Party members were asked to place themselves somewhere on a scale running from zero (very left-wing) to ten (very right-wing). We consider responses of zero and one to be ‘far-left’, two and three to be ‘centre-left’ and four, five and six to be ‘centrist’. As displayed in the figure below, there is considerable difference in the left-right placement of the cohorts. We also add the left-right self-placement of voters as a comparison using British Election Study 2015 data.

Green Party voters’ self-placement on the left-right scale

While current Green members who joined the party before 2010 were overwhelmingly centre-left, the 2010-2013 cohort are almost equally split between those on the far-left and the centre-left, with practically no centrists. The ‘surgers’ of 2014-2015 were between the two groups. In this sense, the Green Surge did not change the left-right position of the party but instead reinforced the move to the left that had already happened in 2010-2013. On the other hand, voters for the Green Party – as is typical of all parties – tended to be far more centrist than the party’s members.

While current Green members who joined the party before 2010 were overwhelmingly centre-left, the 2010-2013 cohort are almost equally split between those on the far-left and the centre-left, with practically no centrists. The ‘surgers’ of 2014-2015 were between the two groups. In this sense, the Green Surge did not change the left-right position of the party but instead reinforced the move to the left that had already happened in 2010-2013. On the other hand, voters for the Green Party – as is typical of all parties – tended to be far more centrist than the party’s members.

When we take a more detailed look at members’ policy attitudes, we see a similar pattern. Those who joined the party before 2010 were the least pro-immigration, least in favour of government redistribution of incomes and the least anti-austerity – though still far to the left of the general public. The party was then dragged to the left on all of these issues by the 2010-2013 cohort. Those who joined during the surge, on the other hand, held views on all of these issues that were almost identical to average views within the party’s membership by 2013.

Somewhat mirroring the changes prior to the surge is the pattern of other organisations to which different cohorts of Green Party members belong. The pre-2010 cohort are nearly four times more likely than the 2010-2013 cohort to be members of the conservationist World Wildlife Association (with the surgers again splitting the difference). On other hand, over a quarter of the 2010-2013 cohort were members of the more radical Greenpeace, more than any other cohort. Not only are the 2010-2013 more radical, but they are also the least likely to believe that both they as individuals and as a party can affect change in their community and country – with the pre-2010 cohort being far less disillusioned and the surgers again splitting the difference (source: PMP).

The key sources of variation in membership brought by the surgers were socio-demographic: gender, education and social class. Whereas there is relative gender parity amongst the pre-2010 cohort (indeed 55 per cent of Green members who joined before 2000 are women), two-thirds of those who joined between 2010 and 2013 were male. Greater gender parity was partially restored during the Green Surge, with 44 per cent of surgers being women. In this sense, the Green Surge shares similarities with the SNP’s and Labour’s membership surges, which were more or less gender-equal phenomena and a far cry from the erstwhile male domination of British political parties (source: PMP).

The Green Surge also broadened the party’s socio-demographic profile by continuing the increasing trend of non-graduates in the party, as started by the 2010-2013 cohort. Whereas 66 per cent of members who joined before 2010 had a university degree, only 59 per cent of the surgers were university graduates. Similarly, while only 29 per cent of the pre-2010 cohort belonged to lower social classes, 36 per cent of the surgers belonged to lower social groups. Thus, although new members have not driven the Greens further to the left, the party seems to have attracted a more balanced profile of members in terms of gender, educational levels and social class.

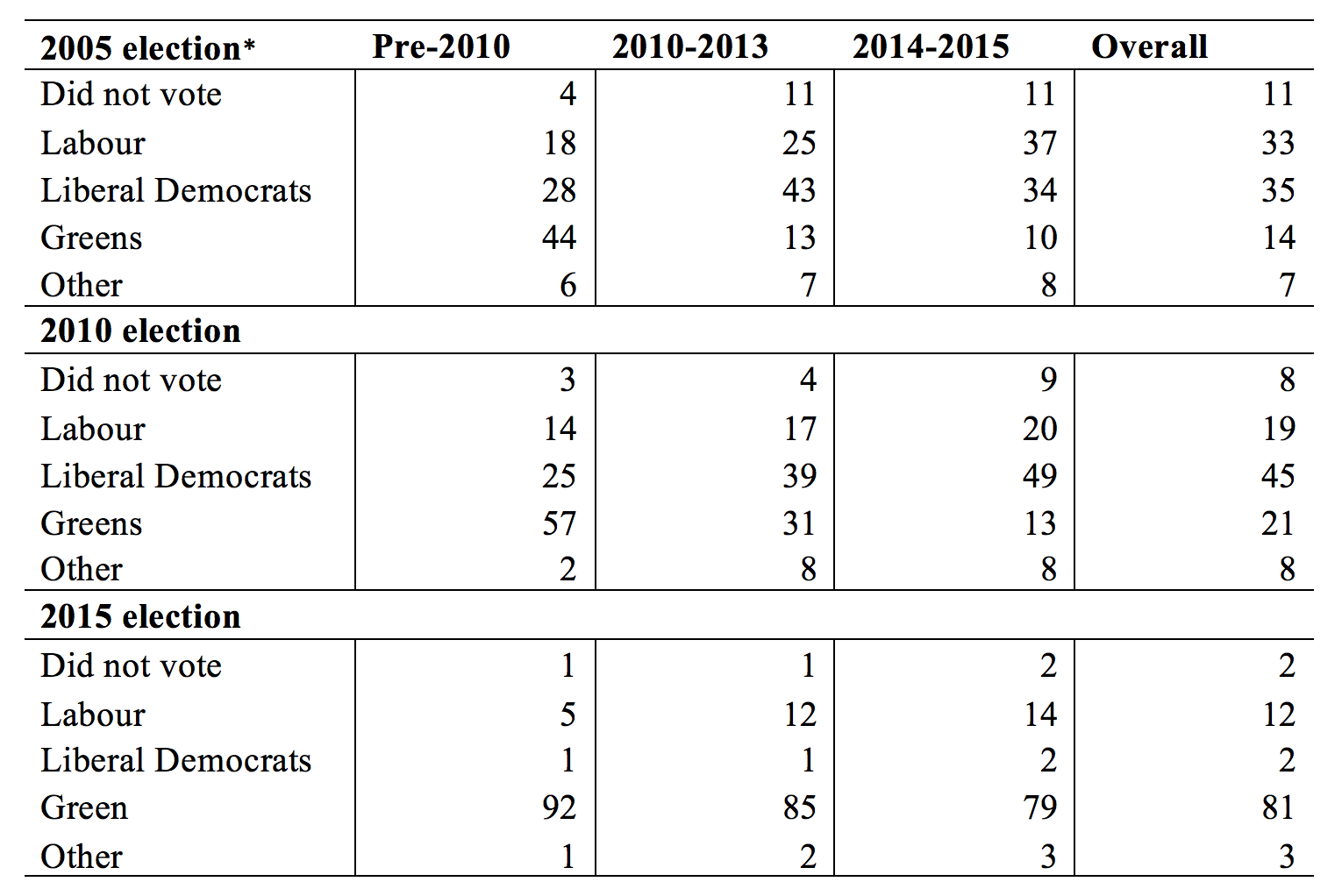

The recent nature of the Greens’ transformation into a more orthodox, ‘vote maximising’ party, combined with their newfound financial capability to stand candidates, is reflected in the relatively limited support of the Green membership for their party at the ballot box prior to 2015. Overall, of those old enough to vote, only 14 per cent of current Green Party members voted for their party in 2005, with only a slight increase up to 21 per cent in 2010. It was only in 2015 that Green members overwhelmingly voted for their party. Another interesting aspect is that the party has managed to engage people who were previously not interested in voting at national elections. The proportion of Green Party members who did not vote dropped from 11 per cent in 2005 to only 2 per cent in 2015.

Two things stand out when looking at each cohort’s voting history. First, Green members often did not vote for their party before 2015 and instead voted either for Labour or, in particular, the Liberal Democrats. The electoral history of the surgers, however, stands out from the other two cohorts. They were the only group that was more likely to vote for Labour in 2005 and then overwhelming supported the Liberal Democrats in 2010, before joining the Greens. They were also the least likely to vote for the Greens in both 2005 and 2010. In this sense, the Green surgers mirror some UKIP voters who, following the breakdown of the Blairite coalition of middle class liberals and anti-immigration Old Labour voters, temporarily moved to another party in 2010 before settling on an ‘insurgent’ party in 2015.

How Green Party member cohorts voted in the last three elections

* 22 per cent of current Greens were too young to vote in 2005 and 12 per cent were too young in 2010.

* 22 per cent of current Greens were too young to vote in 2005 and 12 per cent were too young in 2010.

Second, even in 2015, when most of the party overwhelmingly voted Greens, one in five of the surgers still voted for other parties and, particularly, for Labour (14 per cent). This may be due to tactical considerations but may also reflect that, for this segment of the surgers, their joining was not out of overwhelming support for the party but was instead an expression of sympathy during the controversy over the party’s exclusion from the television leaders’ debate. This suggests that the support of the surgers may not be as durable as the party might like if such a significant proportion did not vote for the party months after joining it.

The party’s membership has clearly been transformed over the last six years. Yet the Green Surge of 2014-2015, despite more than trebling the size of the party and creating a more socio-demographically balanced one, reinforced rather than overhauled ideological changes that had already occurred internally. This does not take away interest from the surge. It rather begs the question why these people joined the party when they did and not before. Part of the answer may lie in their voting history, as many of the surgers first abandoned Labour at the ballot box after 2005 and then the Liberal Democrats after 2010 before settling on the untainted voice of the Greens.

Overall, the Green Surge’s effect on the party was to dilute any significant last vestiges of conservationism or economic centrism in the party ranks, and provided the party with the resources necessary to become England’s most electorally successful radical leftist party in memory. However, given the surgers’ voting history with Labour, both under Blair and for some even in 2015 as card-carrying Green members, it remains to be seen for how long the Greens can keep hold of their newest cohort when confronted by a Labour Party whose own membership surge is certain to have altered its party’s ideological balance.

__

Note: The ESRC Party Members Project (PMP) from which the data is drawn is run by Tim Bale, Paul Webb, and Monica Poletti. Image credit: Global Justice Now CC BY

Monica Poletti is an ESRC Post-Doctoral Fellow in Politics at Queen Mary University of London and co-runs the ESRC Party Members Project (PMP) together with Tim Bale and Paul Webb. She is also a Guest Teacher at the London School of Economics and a Research Fellow of the COST-Action ‘True European Voter (TEV)‘ project.

Monica Poletti is an ESRC Post-Doctoral Fellow in Politics at Queen Mary University of London and co-runs the ESRC Party Members Project (PMP) together with Tim Bale and Paul Webb. She is also a Guest Teacher at the London School of Economics and a Research Fellow of the COST-Action ‘True European Voter (TEV)‘ project.

James Dennison is a Researcher at the European University Institute in Florence and also teaches at the University of Sheffield. His upcoming book The Rise of the Greens in British Politics: Protest, Anti-Austerity and the Divided Left will be published by Palgrave in June 2016.

James Dennison is a Researcher at the European University Institute in Florence and also teaches at the University of Sheffield. His upcoming book The Rise of the Greens in British Politics: Protest, Anti-Austerity and the Divided Left will be published by Palgrave in June 2016.

I would echo the comments above with respect to the inadequacy of the Left-Right paradigm. Respect for nature and the earth has been notably absent from both the Left and Right wings of politics.

However, those voting Green in my experience are far more interested in a more equal society than most voting for Right wing parties so in that sense, of course the Greens are Left wing. The problem is that there are so many concerns both environmental and social that do not fit neatly into those catagories.

Three months after the date chosen for the period of analysis, Green party membership had dropped by over 7000. That suggests that the question about the durability of the membership asked in the opening paragraph may be rather straightforward to answer.

Useful, but I’m very disappointed that you stuck closely to the ‘Left-Right’ spectrum, which is really hopelessly inadequate, when it comes to Green politics. See my analysis here, including of alternatives: http://www.newstatesman.com/politics/elections/2015/09/if-corbyn-becomes-leader-whats-left-greens

The acid test will be at the next election. I believe many more green voters at the last election could have been poached form the Lib Dems if the farther left activists had not made the party’s policies more uncomfortable for them. Many former Lib Dems, perhaps both Green Party members and those who simply rejected them at the last election and supported the Greens as an alternative may return to that party if the Green Party reflects too many Militant attitudes.

A few interesting assumptions here! I interviewed in depth 10 members in 2001 and held focus groups. Many members then, and now, would avoid the terms left and right as both ideological positions rely on ongoing consumption.

The other interesting assumption is that a change in voting reflecting a change in desire to vote for the Green Party rather than increasing opportunity. Typically the Greens have only managed to find the funds and volunteers to stand in 1/3rd or so of constituencies, whereas in 2015 they stood in nearly all constituencies, giving members the chance to demonstrate their support at the ballot box.

Maybe the problem is the idea of left and right wing politics, far left of course would be a dyed in the wool communist not many of those in power even in communist nations, or a far right dyed in the wool fascist which the American and british governments most closely resemble but surely have not quite gone as far yet. perhaps it would be better to just take it that politics generally is centralist and drop the nonsense of the wings.