Posted by Ed Towers and Patrick Dunleavy

Posted by Ed Towers and Patrick Dunleavy

The stage for the election is set. Britain is in the grip of its longest recession since the 1930s. The party in government have enjoyed three successive election victories, but the charismatic leader who provided them is gone. The incumbent Prime Minister was chosen by his party, and has never yet won an election in his own right as party leader. Meanwhile, the leader of the opposition has fought hard to moderate its policies and to move his party back towards the centre ground. He has also eased some of the internal divisions and persistent image problems that have previously hamstrung them. But the public are still questioning whether he has the gravitas and wisdom needed to run a government. Where once an opposition victory looked assured, now the polls have become ‘too close to call’ and many pundits are predicting a hung parliament.

Sounds familiar ? But this is a description of 1992, and not 2010. And as we all know, in 1992 John Major defied all the polls to win a fourth term for the Conservatives and to earn his own electoral mandate. Labour gained 3.4 per cent of the vote but mostly from the Lib Dems, while the Tory government’s share of the vote shrank by just 0.3 per cent.

Could such a surprise outcome happen again in 2010? One or two commentators have begun to note ruefully that it might not be inconceivable now that Gordon Brown could still be Prime Minister in June this year. Andrew Rawnsley, the journalist whose book about new Labour’s internal political divides is title The Party’s Over even speculated in the Observer recently that perhaps he’d have to change the title after all.

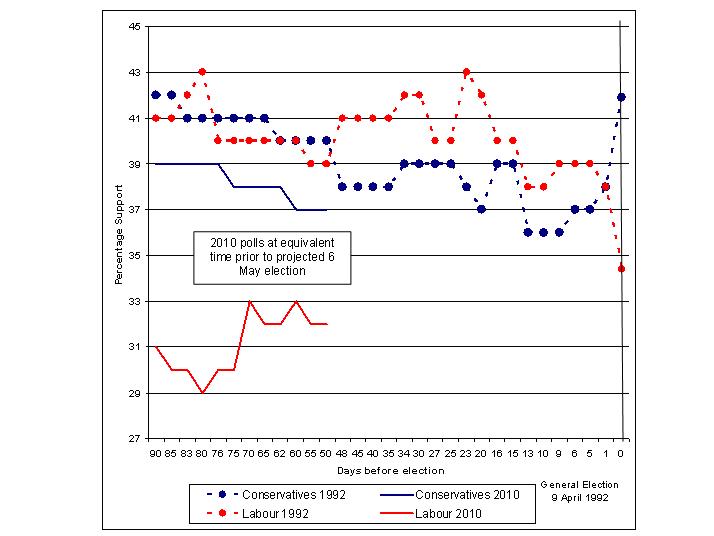

Yet in fact there are some strong differences now from those applying 18 years ago. Many polls leading up to the 1992 election proved to be unreliable. In the two months leading up to the election ICM polls (one of the best-run and most accurate) showed Labour leading the Tories by between 1 per cent and 3 per cent in voting intentions. And on the eve of an election an ICM poll showed the two parties to be level pegging:

1992 and 2010 – Comparative Labour and Conservative Polling

Yet in reality the Tories gained 8 per cent more of the popular vote than Labour, a ‘standstill result’ giving them a majority of 21 seats with 41.9 per cent of the vote. The Tories would need a 7 per cent swing giving them 39.5 per cent of the vote to achieve a similar majority this time around.

Second, the public opinion of the two candidates for Prime Minister in 2010 is radically different to that applying in 1992. Although the 1992 opinion polls underestimated the public support for the Conservatives, on the issue of who would make the best leader, John Major enjoyed a comfortable 15 per cent lead over his Labour rival Neil Kinnock for almost all of 1990-92. By contrast, in 2010 the most recent ICM Poll for The Guardian on March 15th suggests that Cameron is still the most preferred leader. Some 42 per cent of respondents think he would make a better prime-minister, compared to just 28 per cent for Brown. Gordon Brown’s showing has improved in recent weeks, but not enough to make him a winning asset for his party.

A third comparison with 1992 concerns which party was or is most trusted by the public to handle the economy in a period of recession. Despite leading the country into recession the Conservatives in 1992 managed to convince the public that they were also the best placed to lead it out of recession, achieving a 12 per cent lead in the polls on this issue.

Labour has to make the same hard sell today. But unlike 1992 , neither party in 2010 has yet been able to take a decisive lead on this issue. An ICM poll on 5th March asked which party has the best policies on dealing with recession – the Tories just came out on top, but only by 2 per cent (getting 35 per cent to Labour’s 33 per cent). Yet a more recent ICM poll published on 15th March found 12 per cent more people thought the Tories would be better at increasing economic growth. This apparent contradiction suggests that spending cuts continue to be the main concern for voters in recession times, and this is an issue about which the public remains undecided. One of the least well-understood public opinion reactions in recessions is that older voters especially may tend to back the incumbents for fear of getting unwelcome changes if control of government changes hands. So in this area Labour might yet convince voters of the need for a steady hand on the tiller, as John Major did in 1992.

A final area of useful comparison to consider might be whether it’s a good idea for a failing party to get an extension of its time in government, if the ‘will to power’ and zeal for office is no longer the beating life-forces of the governing party that it once was. Notoriously John Major won office in early summer 1992 only to descend into the vortex of Black Wednesday in autumn the same year, when Britain had to leave the European Exchange Rate Mechanism. This economic crisis over-shadowed the whole of the next five years, and lead to a step change down in Tory opinion poll ratings for more than a decade, from which Cameron has only just managed to somewhat revive them.

Seen in these terms, and against the background of the UK’s mounting public deficit problems, would a late renaissance in Labour support actually damage the party. If it enabled Gordon Brown to hang on after the election, the same problems that have faced his leadership may still re-surface. Having Brown still at the helm might also harm Labour’s chances of forming a coalition government with the Liberal Democrats in the event that there is a ‘deeply hung’ parliament.