The possible spending plans of Labour and the Tories illustrate the fact that there are real choices to be made at the election, writes John Van Reenen.

The possible spending plans of Labour and the Tories illustrate the fact that there are real choices to be made at the election, writes John Van Reenen.

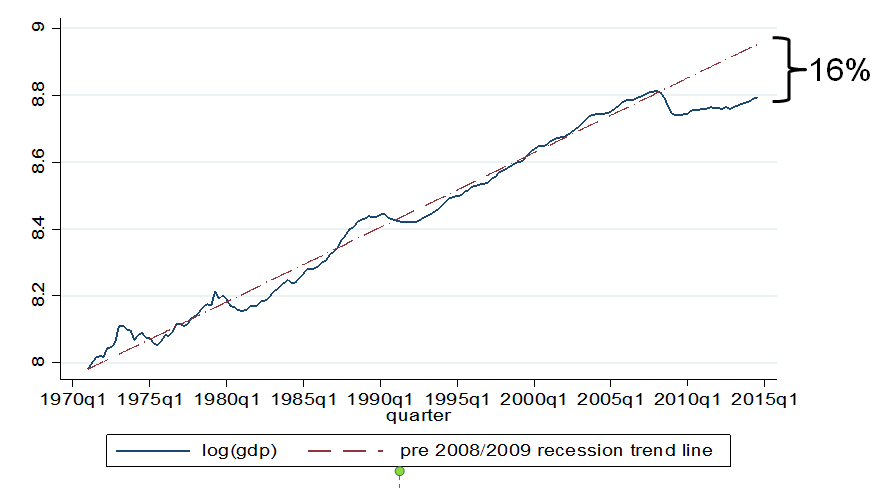

When viewed over the longer term, the state of the UK economy is not pretty. National income per person is today about 16 per cent below where it would be on pre-crisis trends (see Figure 1). This is a dismal performance and reflects the worse recovery in living memory.

Figure 1: A dismal economy? GDP per person is now 16% below trend

Notes: Trend line at 0.558% per quarter (linear trend from 1970Q1 to 2008Q1 when recession began). Growth 2010Q2 to 2014Q3 was 0.195% per quarter. Quarterly Gross domestic product (average) per head (series IHXW), market prices (downloaded February 23rd)

How does this fit with the more rosy view of the Chancellor epitomised by the buoyant jobs market? It is true that over 73 per cent of working age people are in jobs, back to pre-crisis levels. But a major factor in the “jobful” recovery is an 8-10 per cent fall in real wages. People “priced themselves into jobs”, but at a ferocious cost to living standards for those of working age.

Alongside earnings, the productivity numbers also make grim reading: UK output per hour is now about 30 per cent lower than in the US, Germany and France. So maybe it’s unsurprising that no reference was made to productivity in the Budget. But an important election question is what can be done to return to relatively healthy growth in productivity enjoyed in the three decades leading up to the financial crisis? Business policies, human capital and infrastructure all have important roles to play.

Looking back on austerity

Some of the poor growth performance is outside the government’s control. The Chancellor cannot be blamed for the even more aggressive austerity in the Eurozone that is pushing the region into deflation.

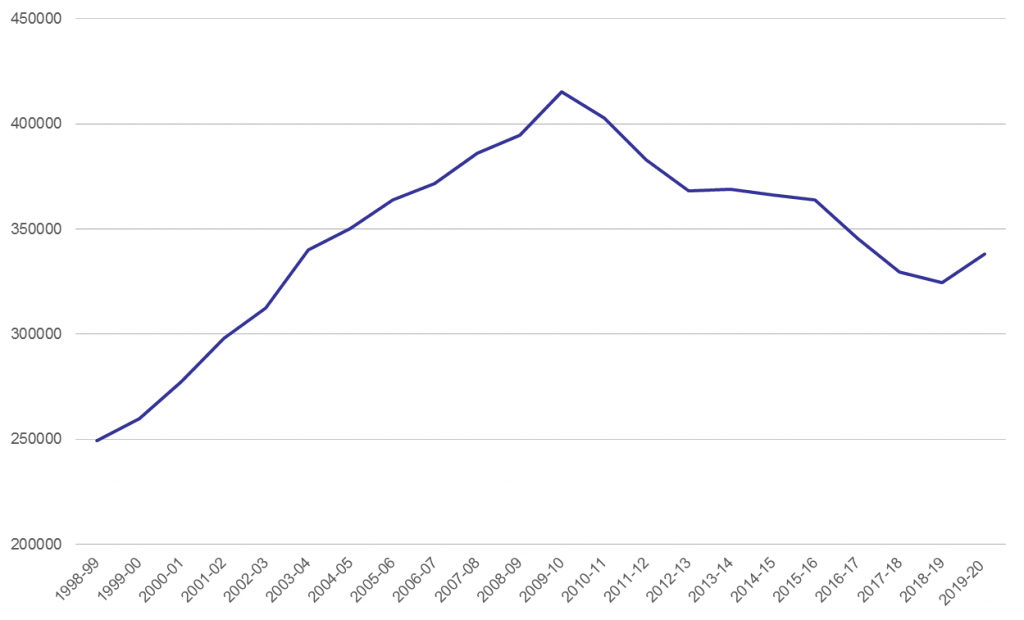

But the public finances are something that are more in the government’s remit. Looking back, the government will have cut spending on public services by 9.7 per cent in real terms 2010-11 to 2015-16. These cuts were very severe in the first two years of the coalition (see Figure 2) but levelled off after 2012-13 as the nascent recovered stuttered out. The slowdown in austerity pushed much fiscal consolidation until the next Parliament and was a sensible response to the flat-lining of the economy. The OBR reckons that austerity measures knocked 2 per cent off GDP in 2010-11 and 2011-12, but the true figure is likely to even worse. Recent research has shown that government spending cuts have much larger effects in deep downturns when interest rates are near zero as they have been since the crisis. This is particularly so when the cuts are to investment, which is why the 40 per cent public investment cuts over the first half of the Parliament were so damaging.

Figure 2: Departmental spending, £million

Source: PESA (various years), 2015-16 prices, Total DEL (public service spending)

Looking forward to more austerity?

Looking forward, the Chancellor has promised to return to the deep spending cuts in the first half of this Parliament. According to the fiscal watchdog, the OBR, day to day public service spending is scheduled to fall in real terms by 5 per cent in both 2016-17 and 2017-18. These are larger than any cuts achieved in a single year of this parliament. Strangely, this is followed by a big splurge in 2019-20 as spending is allowed to grow with GDP. So there will be a £40 billion cut to 2018-19 (compared with a £39 billion cut 2010-11 to 2015-16) followed by an increase of £14 billion. The OBR is correct to describe this as a “rollercoaster” – why not smooth out the cuts more gently than this?

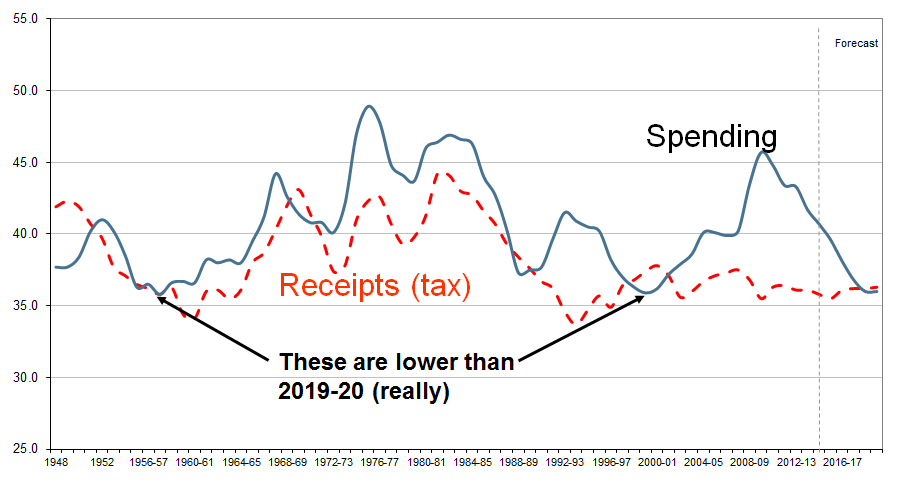

The answer is electoral. By reversing his aim in the December Autumn statement to create a £23 billion surplus in 2019-20, the Chancellor now predicts that public spending will be 36 per cent of GDP. So this is not “to the level of the 1930s”, as the equivalent number in 1999-2000 was a 35.9 per cent; a whopping one tenth of one percent lower (Figure 3)!

Figure 3: government spending (TME) and receipts as percentage of GDP, 1948-2020

Source: OBR Public Finance Database (March, 2015)

The Chancellor objects to the OBR analysis, pointing out that it does not include his £12 billion of welfare cuts. But in the two years since these were announced, the only details we know are on £2 billion of these cuts and the fact that that pensioners, once again, will not have to suffer any cuts at all.

None of this should disguise the fact that aiming to shrink the state permanently to 36 per cent of GDP is a radical proposition. It will be much smaller than the post war average. And since welfare spending – and pensions in particular – are an increasing share of all public spending, resources devoted to public services as a fraction of national income is still destined to shrink to a low not seen in generations.

And all this is before taking into account many of the new pressures on public spending such as an expanding and ageing population, a likely recovery of wages in private sector (making public sector wage freezes harder) and higher public sector NICs and pension contributions. These will put departmental budgets under even more pressure.

Some Big Choices in the Ballot Box

To illustrate the differences between the parties consider some possible spending scenarios. The first column of Table 1 looks at the Coalition’s current plans from 2015-16 to 2019-2020. Public services are due to be cut by £26 billion in real terms over this period, a 7.2 per cent fall. Health, schools and overseas aid are “protected”, so are looking at a real terms increase of £4.7 billion. By contrast, the unprotected departments are looking at a £30.8 billion fall.

Table 1: Big choices – possible spending plans 2015-16 to 2019-20

| £billion real (% change) | Coalition plans | Conservatives | Labour |

| DEL (public services) | -26.0 (-7.2%) | -13.6 (-3.7%) | 9.2 (2.5%) |

| of which: | |||

| “protected” | 4.7 | 4.7 | 5.0 |

| “unprotected” | -30.8 (-15.7%) | -18.3 (-9.4%) | 4.3 (2.4%) |

Source: OBR & IFS calculations

Interestingly, the coalition policies are tougher than is required by the Conservatives under their self-imposed fiscal rules to balance the overall budget by 2018-19. They are aiming for a £7 billion surplus in 2019-20 rather than zero. They are also planning to cut £12 billion from welfare to fund a £6 billion tax giveaway. This £13 billion could be used to have a slower path of DEL (public services) cuts as shown in the second column of Table 1.

Finally, Labour have pledged to balance the current budget deficit by 2019-2020, which does not include investment spending. This means that they could reduce borrowing more slowly, so long as the spending is used for capital like building schools rather than increasing salaries. In principle, Labour could actually increase spending – by £9.2 billion overall and even by £4.3 billion in unprotected departments.

Conclusions

These are all projections a long way out and involve a lot of guess-work. Nevertheless, they do illustrate the fact that there are real choices to be made at the election. The difference between public service spending under Labour compared to the coalition could be £35 billion by the end of the next Parliament. To put this in perspective, an increase in the basic rate of tax by 6p raises about £33 billion, so these are not trivial policy differences.

Labour (and to a lesser extent the Liberal Democrats) would spend more, especially on public investment, but reduce debt more slowly as a fraction of GDP than the Conservatives. Given the long-standing problems of low investment in the UK economy highlighted by the LSE Growth Commission, this is a serious matter. It reflects some real choices to be made this election.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

John Van Reenen is Professor of Economics and Director of the Centre for Economic Performance at LSE.

John Van Reenen is Professor of Economics and Director of the Centre for Economic Performance at LSE.

1 Comments