Drawing on spatial analysis of local authority budgets, Mia Gray and Anna Barford highlight the uneven impacts of UK austerity. They argue that it has actively reshaped the relationship between central and local government, shrinking the capacity of the local state, increasing inequality between local governments, and exacerbating territorial injustice.

Drawing on spatial analysis of local authority budgets, Mia Gray and Anna Barford highlight the uneven impacts of UK austerity. They argue that it has actively reshaped the relationship between central and local government, shrinking the capacity of the local state, increasing inequality between local governments, and exacerbating territorial injustice.

Contemporary austerity in Britain has become both a powerful political discourse and an integrated policy of rapid cuts to state expenditure. Although there was considerable public debate about the wisdom of austerity – its pace and its scope – politicians and much of the popular media presented a narrative around austerity that invoked inevitability, the probable consequences of spooking financial markets, and the prudence of fiscal responsibility. Our research explores the spending cuts in local authority budgets in the UK and examines the relationship between the local and central government. We argue that austerity has actively reshaped the relationship between central and local government in Britain, shrinking the capacity of the local state, increasing inequality between local governments, and exacerbating territorial injustice.

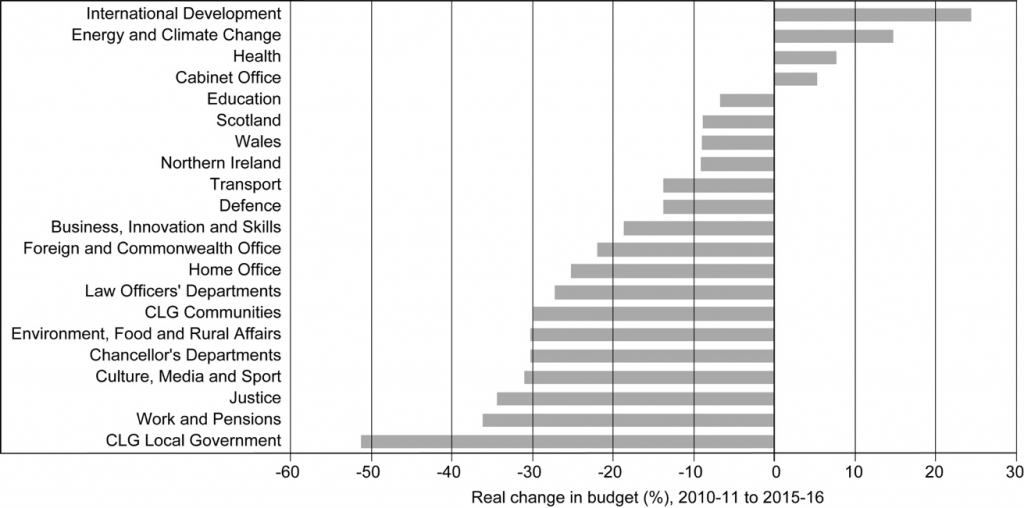

UK austerity policy focused on across-the-board budget cuts to almost all government departments. By far the largest cuts between 2010 and 2015 fell upon local government which lost over half its funding during this period (Figure 1). These cuts have been very uneven, both between local authorities and in which services suffered the greatest cuts. Simultaneous state restructuring has meant that additional public service provision is pushed down to lower levels of government with no corresponding revenue stream – concentrating the tensions and politics of national fiscal crisis onto local government. Within local government, councillors weigh service areas up against one another, making forced choices as to where to cut the most. Planning and development services, which to many on the political right is the exemplar of the “bloated” and bureaucratic state, seemed a particular target and lost over half (53%) of their spend between 2010 and 2016.

Figure 1. Real-terms cuts in departmental expenditure limits, 2010–11 to 2015–16.

Note: The 2015-16 defence budget includes the special reserve. The CLG Local Government budgets for Wales and Scotland are adjusted for council tax benefit localisation and business rates retention. Source: Institute for Fiscal Studies (2015), ‘Recent cuts to Public Spending’. Based on HM Treasury Data (July 2015 Budget).

Note: The 2015-16 defence budget includes the special reserve. The CLG Local Government budgets for Wales and Scotland are adjusted for council tax benefit localisation and business rates retention. Source: Institute for Fiscal Studies (2015), ‘Recent cuts to Public Spending’. Based on HM Treasury Data (July 2015 Budget).

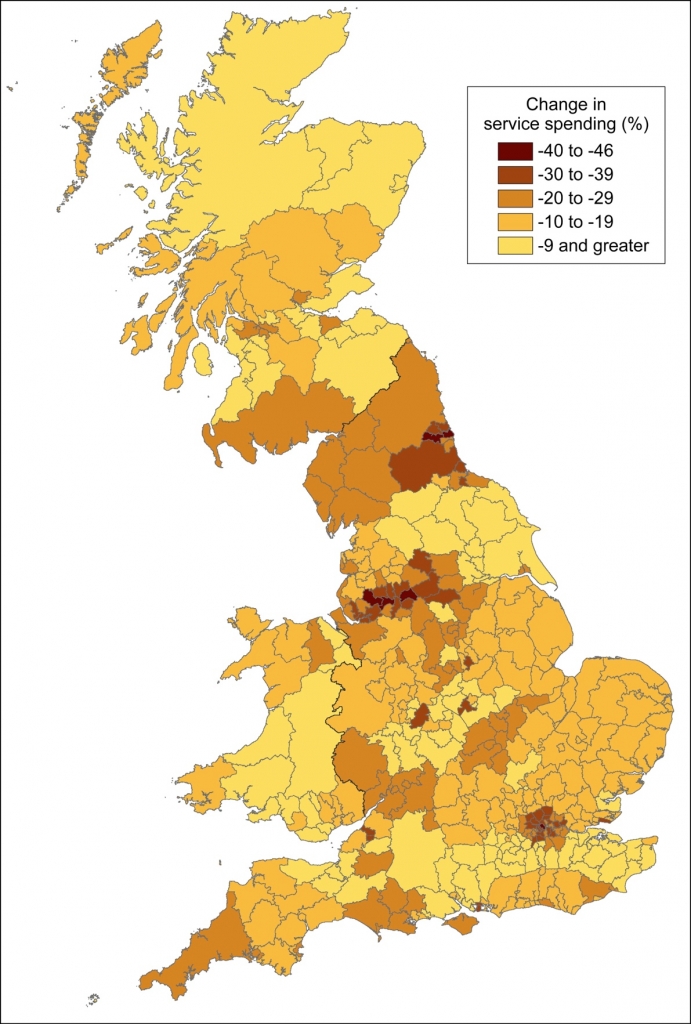

Despite having good data on total national cuts in departmental funding, including for local government expenditure, patterns of cuts and the specificities of how local economies are affected are harder to come by. Analysis of government data by the Institute for Fiscal Studies offers insight into the geography of local government austerity. The biggest spending cuts, and highest grant dependence, tend to exist in cities. This pattern is clear in many London boroughs and cities such as Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham, Portsmouth, Oldham, Middlesbrough, Newcastle, Nottingham and Doncaster; all received a high proportion of their funding from the central grant, and experienced cuts of over 25% to total service spending (Figure 2). Wales and Scotland have been buffered from the depths of the English budget cuts.

Figure 2. Map of change in service spending in Wales, Scotland and England, 2009-10 to 2016-17.

Note: The Welsh data show service spending, excluding education spending and housing benefits. The Scottish data exclude education spending. The English data exclude police, fire, public health, education, and elements of social care spending. Map drawn using data sourced from the Institute of Fiscal Studies, Amin-Smith et al. (2016).

Note: The Welsh data show service spending, excluding education spending and housing benefits. The Scottish data exclude education spending. The English data exclude police, fire, public health, education, and elements of social care spending. Map drawn using data sourced from the Institute of Fiscal Studies, Amin-Smith et al. (2016).

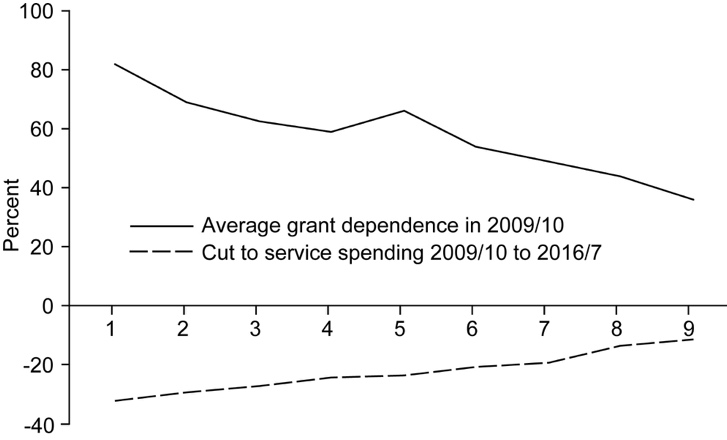

Austerity budgets have exacerbated the division between those cities which have the economic resilience to withstand these cuts and those that are unable to do so and are forced to downsize local government and retrench public services. Variations between authorities (in terms of funding, local tax-base, fiscal resources, assets, political control, service-need and demographics) lead to great variation in spending cuts. The funding from the central state results from a funding formula which largely allocates budgets according to need. Thus, it acts as a mechanism to redistribute tax revenue to areas with the highest need – but also renders the same areas the most vulnerable to budget cuts (Figure 3). This vulnerability is evident from the past seven years: the places which are most dependent on money from central government have cut service spending most severely, in order to meet the legal requirement of balanced budgets.

Figure 3. Grant dependence and service spending cuts in England.

Note: This graph shows the relationship between percentage of local authority grant dependence in 2009/10, and service spending cuts 2009/10-2016/17. Local Authorities are sorted into decile groups according to level of grant dependence, hidden by this are the extremes of the City of London being the most grant dependent at 95% and Wokingham Unitary Authority being the least grant dependent at 28%. This graph has been redrawn, based on the original produced by the Institute of Fiscal Studies, Amin-Smith et al. (2016).

Austerity pushed down to the level of local government in the UK has led to:

- a shrinking capacity of the local state to address inequality;

- (ii) increasing inequality between local governments themselves;

- (iii) intensifying issues of territorial injustice.

Some local authorities have moved to a position of only providing the most basic functions and dropping many preventative interventions, and those with the biggest service spending cuts will be withdrawing services the fastest. A very serious outcome of this is that removing structures of social support paves the way for more sizable case loads in the future. More broadly, austerity at the local level is part of a longer-term political project to re-shape and redefine the welfare state, shifting responsibility for societal well-being towards individuals, the private sector, and the third sector. This research shows how austerity compromises a major redistributive function of the local state, exacerbating territorial injustice in an already highly unequal nation.

_______________

Note: the above draws on the authors’ published work in the Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society. The full article is available on open access and the research is funded by the Cambridge Political Economy Society Trust, the British Academy and the Canada-UK Foundation.

Mia Gray is a Senior Lecturer in Geography at the University of Cambridge and Fellow of Girton College.

Mia Gray is a Senior Lecturer in Geography at the University of Cambridge and Fellow of Girton College.

Anna Barford is a College Lecturer in Geography at the University of Cambridge, Fellow of Girton College, and Bye Fellow of Murray Edwards College.

Anna Barford is a College Lecturer in Geography at the University of Cambridge, Fellow of Girton College, and Bye Fellow of Murray Edwards College.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain).

5 Comments