For those who have followed the public spat in recent months between the Home Secretary and the former chief of the UK Border Force, Brodie Clark, the publication of the Independent Chief Inspector’s report last week helped to shed a degree of light on the underlying complexities of it all. The report, argues Simon Bastow, gives an insight into tension between political priorities and operational imperatives, and how actors at all levels in large policy systems generally adapt to and do their best despite being constrained by the systems in which they work.

For those who have followed the public spat in recent months between the Home Secretary and the former chief of the UK Border Force, Brodie Clark, the publication of the Independent Chief Inspector’s report last week helped to shed a degree of light on the underlying complexities of it all. The report, argues Simon Bastow, gives an insight into tension between political priorities and operational imperatives, and how actors at all levels in large policy systems generally adapt to and do their best despite being constrained by the systems in which they work.

Students of public policy could do worse than pick up a copy of John Vine’s 80-page report into the controversies surrounding suspensions of biometric security checks on incoming passengers at UK ports throughout 2010 and 2011. In a forensic way, it helps to cut through some of the j’accuse-style recriminations which have rebounded across the policy and implementation divide in recent months. But it also provides a valuable insight into the dynamics involved when systems move from situations of chronic capacity stress to more acute manifestations of, let’s face it, crisis.

At the heart of the problem is an acceptable and manageable equilibrium between the pragmatics of operating a large and complex border system on the one hand, and prevailing policy and political priorities on the other. The fact is that since at least 2007 we have run a border control system which has relied on and indeed normalized a degree of suspensions of certain security checks, necessarily in order that ports are able to cope with spikes in demand. As Vine’s report shows, intermittant suspensions of checks against the Warnings Index (WI) (approx. 100 minutes per month across all ports) have been sanctioned by ministers in principle, and justified by officials on a range of pragmatic operational grounds.

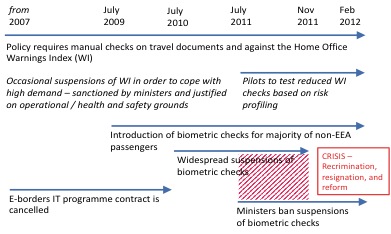

The problem has come with the introduction of a new system of Secure ID (since 2009), requiring that visa holders entering the UK must also be checked against biometric data. This new burden on capacity led to regularized and almost systematic suspension of biometric checks during periods of peak demand. Suspension of biometric checks at Heathrow alone was equivalent to around 100 minutes per day between June 2010 to November 2011. As the timeline below shows, in July 2011, the Home Secretary explicitly forbade these suspensions, yet top managers nevertheless allowed them to continue, albeit at much reduced levels compared to months prior to this ministerial ban.

TIMELINE OF KEY EVENTS LEADING TO THE CRISIS

What to make of all this then? From the Home Secretary’s perspective, the view from the top may be entirely restricted. Former holder of this office, Kenneth Baker, once wrote of prisons that ‘most Home Secretaries cross their fingers and hope that things will not go wrong while they are in office’, and much the same can be said of immigration. Indeed, this anxiety explains in large part why the Immigration and Nationality Directorate (IND) remained part of the Home Office so long after the heyday of ‘executive agency’ creation during the early 1990s. It it was not until 2007 that John Reid created the Border and Immigration Agency.

It is also understandable that ministers may be inclined to sanction certain kinds of border check suspensions, such as WI, if their officials can finesse them in terms of ‘sensible’ risk management or necessary on the grounds of avoiding images of ‘airport queue chaos’ on the 9 o’clock news. Yet it is also understandable that they are likely to want to act quickly and ruthlessly in situations where they are blindsided by operational failure, or openly misled or contradicted by officials.

Top officials, however, are equally constrained by the system in which they operate. The fact that the IND managed to resist managerialist change for so long suggests that it has been a chronically late starter in terms of developing strong managerial cultures, and managers have had to cope with with almost continual structural change in the period since.

In addition, particularly throughout 2010-11 it has had to find considerable reduction in staff numbers (around 8 per cent) and budget (around 12 per cent), comparative at least to earlier years. This has also coincided with the termination of the contract for the e-Borders programme in July 2010. Coping with this technical disruption was a major part of the need to suspend controls at peak times.

As Vine points out, top officials have had to cope with the operational implications of policy not being written down or specific enough, and being left to interpret the significance of rules and guidelines in fraught situations. The fact that the number of suspensions reduced significantly once the ministerial ban had been issued suggests that managers were atttempting to comply, yet it is hard to know what else these managers could do when faced with serious build-up of passengers, perhaps unexpected staff shortage, and a dysfunctional biometric IT system.

Coping cultures tend to encourage benign forms of resistance to change, and managers and staff act in ways which contribute to the system’s inability to respond to increases in demand. This is likely to be particularly the case in established professional cultures, such as customs, far removed from the rarefied policy world of Westminster and Whitehall.

Indeed, dynamics of coping and benign resistance are likely too complex. For example, Vine found that between January and June 2011, biometric reading equipment had been deactivated 14,812 times (p14), and that the Agency was unable to explain why these deactivations had occurred. We might interpret this as managers and staff choosing to rely on tried-and-tested systems during times of pressure. But we may also intepret this as managers and staff behaving in ways which perpetuate the importance of human processes during times of staff cuts. Either way, as Vine points out, ‘many staff, at varying grades, questioned the rationale of installing a biometric system for it only to be bypassed at times of pressure in the immigration arrival hall’ (p43).

We see here how coping cultures and benign forms of resistance in complex systems can perpetuate often quite striking signs of obsolescence and inefficiency. The irony being that millions of pounds are spent on brand new IT systems which cannot be used effectively, for one reason or another, at the times when they are most required. Other signs in the report illustrate peculiarly obsolecent practices embedded in so-called modern systems information management systems. For example, recording of suspensions in Heathrow terminals is carried out in manual log, and in one case, in an A4 lined book! (p41)

These points are interrelated. They also above remind us that such acute manifestations of crisis can often conceal more chronic situations of capacity stress and constrained autonomy. One has to feel a certain sympathy for Brodie Clark, who was wrongly allowed to be portrayed by the Home Office as a ‘rogue civil servant’ solely responsible for these failings. His own situation of constained autonomy makes this portrayal impossible.

Meanwhile, the UK Border Force will be split from the UK Border Agency, and made directly responsible to the Home Secretary as an agency itself. This is in effect the creation of a new operational agency within an existing one. Given that a major theme of Vine’s report is the complete lack of integration between policy and operation of the system, one wonders how this planned separation of policy and operation of system will help to alleviate this problem. Nevertheless, for the Home Secretary, the matter has been seen to have been dealt with by declaration of intended reform. It remains to be seen how effective this will be in addressing more underlying governance problems at the heart of it all. Only partly, I would say.

Please read our comments policy before posting.