What does the British public think about climate change? Is there strong public pressure on politicians to enact policy to bring down emissions? Drawing on online survey data, Sam Crawley, Hilde Coffé and Ralph Chapman explain that there are five climate change opinion ‘publics’. The two largest publics have strong beliefs that climate change is occurring, but view it as a low salience issue.

What does the British public think about climate change? Is there strong public pressure on politicians to enact policy to bring down emissions? Drawing on online survey data, Sam Crawley, Hilde Coffé and Ralph Chapman explain that there are five climate change opinion ‘publics’. The two largest publics have strong beliefs that climate change is occurring, but view it as a low salience issue.

The UK is often thought of as a world leader in addressing climate change, being among the first countries to pass legislation setting binding targets for emission reductions. However, concerns have been raised about how well the UK is living up to its commitments, with a June 2019 report by the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) finding that the UK “is lagging behind what is needed to meet legally-binding emissions targets”.

Survey evidence has shown that a large majority of the UK public is concerned about climate change, and would like something to be done about it. Does this strong public support for action on climate change suggest that politicians are ignoring public preferences?

Belief, issue salience, and support for government action

A lot of the existing research on public opinion on climate change focusses on people’s beliefs about climate change (e.g. whether or not they believe climate change is happening and are concerned about it). However, this focus tends to (implicitly) categorise people as either “believers” or “deniers”.

To get a more comprehensive picture of public opinion on climate change, we surveyed nearly 800 people in the UK in August 2018. We asked people about their climate beliefs, but also questions on the relative importance of climate change (issue salience), and whether or not they support government action to address climate change. We were interested in finding out if some people are concerned about climate change but consider it a low salience issue, or do not support government action to address it.

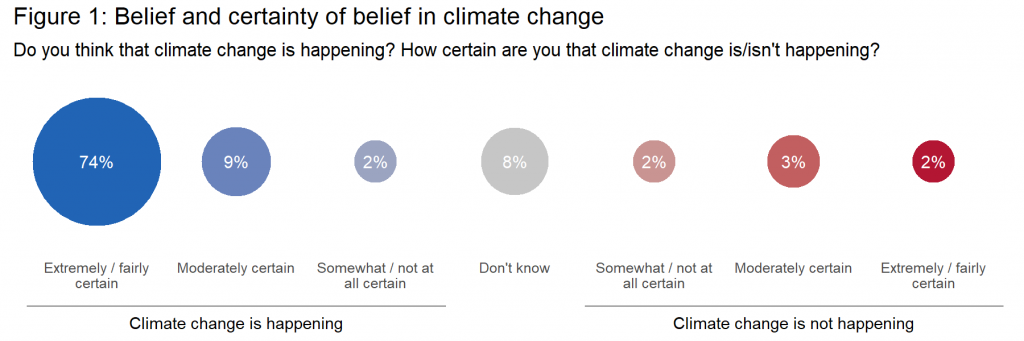

With respect to climate beliefs, as illustrated in figure 1 below, only 7% of our respondents thought climate change is not happening, although more than half of those were not confident in their views. 74% of respondents thought climate change is happening and are fairly or extremely confident in that position.

Regarding other aspects of climate belief, 72% of people surveyed thought that climate change is mostly caused by humans, and 73% believed that most scientists agree that climate change is happening.

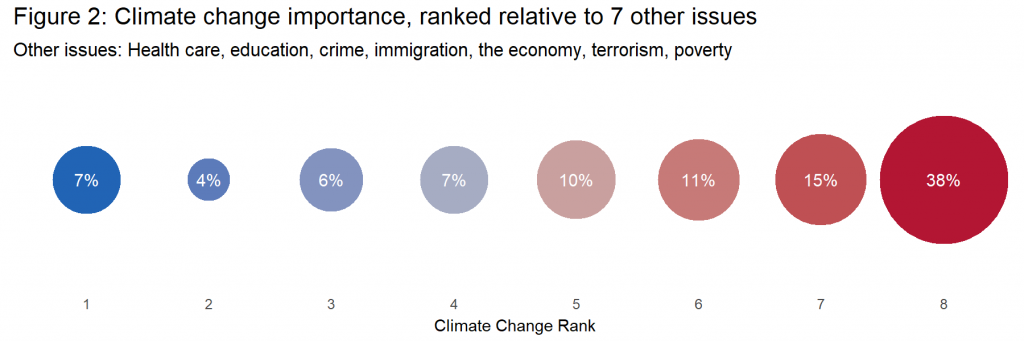

To find out about issue salience, we asked people to rank eight issues (climate change, health care, education, crime, immigration, the economy, terrorism and poverty) from the most to least important to the country. The results – presented in figure 2 – illustrate that the salience of climate change is very low, with 53% of people putting climate change in the bottom two of the eight issues, and only 7% of people believing it is the most important issue.

Finally, looking at support for government action to address climate change, most respondents support the government doing something about climate change, with 78% of people believing that government action (rather than individual action) is the most effective way to solve climate change, and 61% believing the government is not doing enough on climate change. However, only 32% of people are willing to pay higher taxes to help combat climate change.

The “publics” of climate change

Social scientists often think about the population not as a single “public”, but as a collection of multiple “publics”, each with their own perspectives on particular issues. We used the idea of multiple publics to help us understand public opinion on climate change in a way that moves beyond the believer/denier dichotomy. Our study is therefore similar to the “Six Americas” study conducted by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. Using our survey results, we identified five different publics: the highly engaged, the moderately engaged, the action-wary, the uncertain and the deniers.

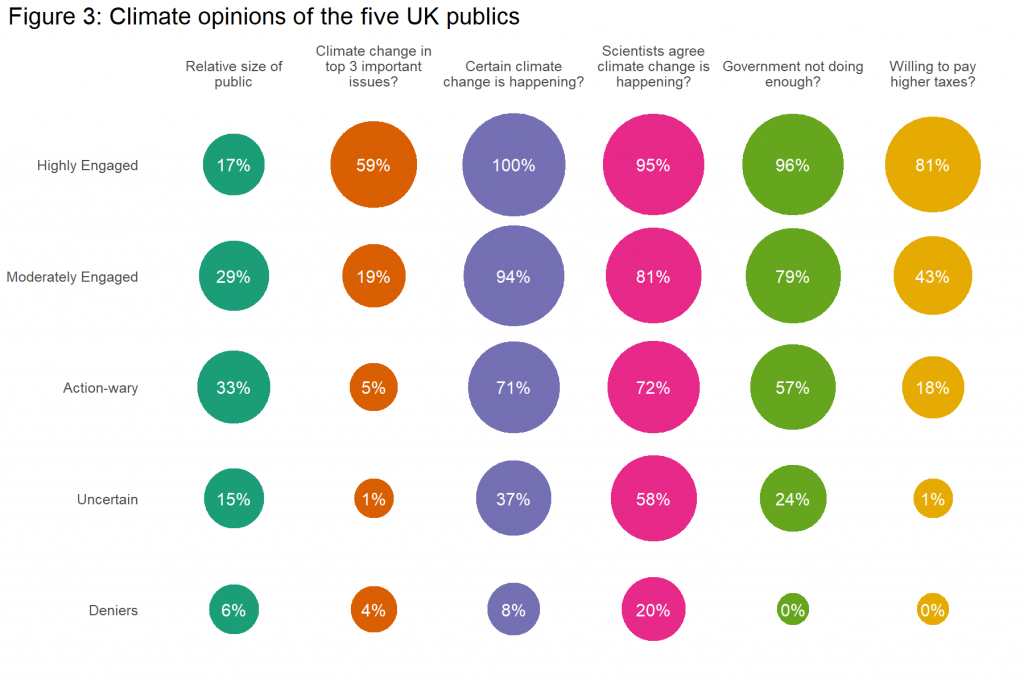

Figure 3 below shows the relative size of each UK public, as well as the percentage of people in each public that hold particular climate change views. The “highly engaged” are concerned about climate change, rank it as a high importance issue, and support government action to address it. The “moderately engaged” are similar to the highly engaged, except that they tend to rank climate change as only a medium importance issue. The “action-wary” are concerned about climate change, but rank it as low salience, and have some concerns about government action to address it. The “uncertain” are unsure whether or not climate change is happening, and are generally against government action on climate change. The “deniers” tend to be fairly certain that climate change is not happening, and think that the government is doing too much to combat climate change.

We also investigated whether the publics had any characteristics in common. We found that older people are more likely to be deniers, and slightly less likely to be highly or moderately engaged. The highly engaged are more likely to be on the left of the political spectrum, while the action-wary and the uncertain tend to be on the right. Education is also important, with the uncertain less likely to hold a degree, while the highly engaged are more likely to have completed a degree.

Political implications

How might this picture of public opinion impact the adoption of ambitious climate policy? Politicians often take the time to understand what the public thinks about a particular issue and use that knowledge to guide their decisions. They are not likely to take big, bold actions (of the type required to address climate change) if they do not feel they are under public pressure to act. That pressure primarily comes through elections, where politicians are worried about keeping their jobs.

When people vote, they tend to have – at most – only a handful of issues in mind. As we have shown with the results of our survey, for most people, climate change is not one of those issues. The salience of climate change is low, and only about 17% of the UK population can be considered as being “highly engaged” with climate change. This means that politicians are simply not under substantial public pressure to act on climate change, as they know it is not one of the main issues that decide most people’s vote.

Several factors are likely contributing to the inadequate action on climate change in the UK described in the CCC report mentioned earlier. These factors include the influence of fossil fuel companies, the long-term nature of climate change, and the personal preferences of politicians. However, the low salience of climate change among the public means that politicians have the space to avoid taking the bold actions required to comprehensively address climate change.

_________________

Note: the above draws on the authors’ published work in The British Journal of Politics and International Relations.

Sam Crawley is a PhD candidate at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand.

Sam Crawley is a PhD candidate at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand.

Hilde Coffé is Professor in Politics at the University of Bath.

Hilde Coffé is Professor in Politics at the University of Bath.

Ralph Chapman is Postgraduate Programme Director in the School of Geography, Environment and Earth Sciences at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand.

Ralph Chapman is Postgraduate Programme Director in the School of Geography, Environment and Earth Sciences at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.