David Cameron was the Prime Minister who promised and delivered a referendum on EU membership, shortly after which he left politics. How did he present the UK–EU relationship during his premiership? Monika Brusenbauch Meislová finds that he adopted a combination of antithetical sub-discourses, which he naturally failed to integrate into a coherent and sustainable discourse.

David Cameron was the Prime Minister who promised and delivered a referendum on EU membership, shortly after which he left politics. How did he present the UK–EU relationship during his premiership? Monika Brusenbauch Meislová finds that he adopted a combination of antithetical sub-discourses, which he naturally failed to integrate into a coherent and sustainable discourse.

Under the premiership of the David Cameron, the relationship between the UK and the EU took a dramatic turn. It was him who, in 2013, under sustained pressure from his own backbenchers, made a commitment to renegotiate the UK’s relationship with the EU and hold an in/out referendum, having plunged Britain’s position in Europe into the greatest uncertainty in generations.

To understand Cameron’s European legacy, it is essential to understand his European discourse. Cameron’s EU policy has been widely interpreted as inconsistent and ambiguous, and I argue that it was the conflicting discourses and rival imaginings on the UK–EU bilateral relationship that help explain the high degree of ambivalence, paradox and misunderstanding associated with his EU policy.

Drawing on insights from the theory of critical constructivism and its relation to discourse, I worked from a core assumption that talking about the relationship between the UK and the EU does not merely describe a given (or envisioned) reality; it also constructs it. As such, Cameron’s perceptions of the UK–EU relations did not only impact the political landscape on which debates over Britain’s future relationship with (and within) the EU were playing out, but also had direct implications for the practice of the UK’s EU policy. It is after all, the Prime Minister who fundamentally shapes the content and direction of the British official discourse on the EU.

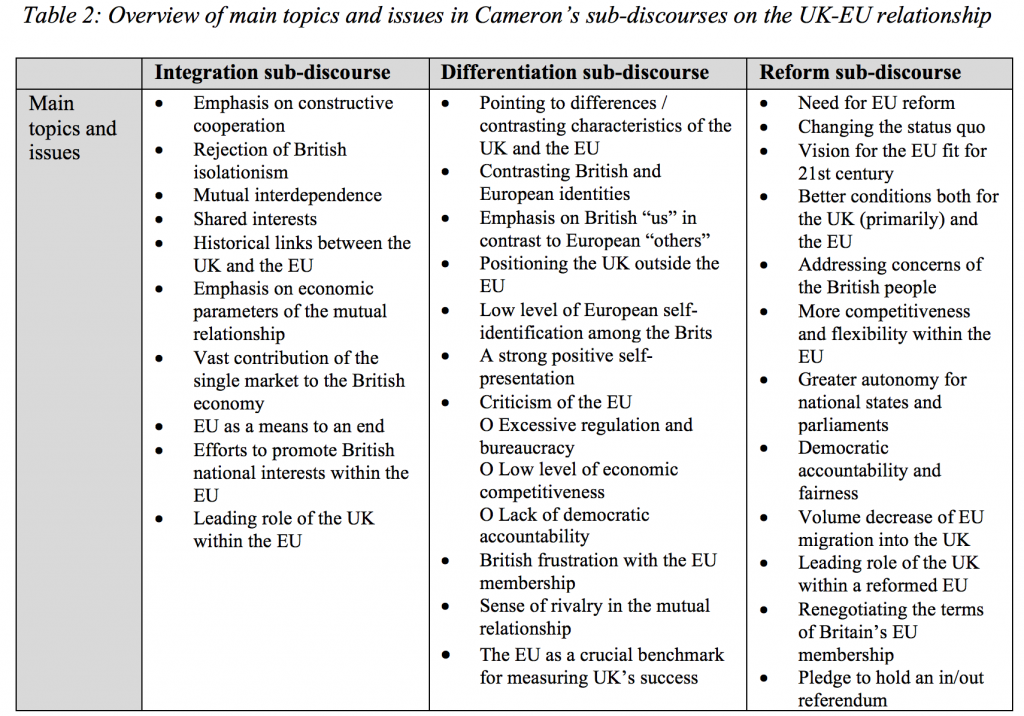

A detailed analysis of Cameron’s 60 official speeches showed that his discourse on the UK–EU relationship was highly complex, varied, and multi-layered. More specifically, it revealed three dominant sub-discourses: (1) of integration; (2) of differentiation and (3) of reform.

Three dominant sub-discourses

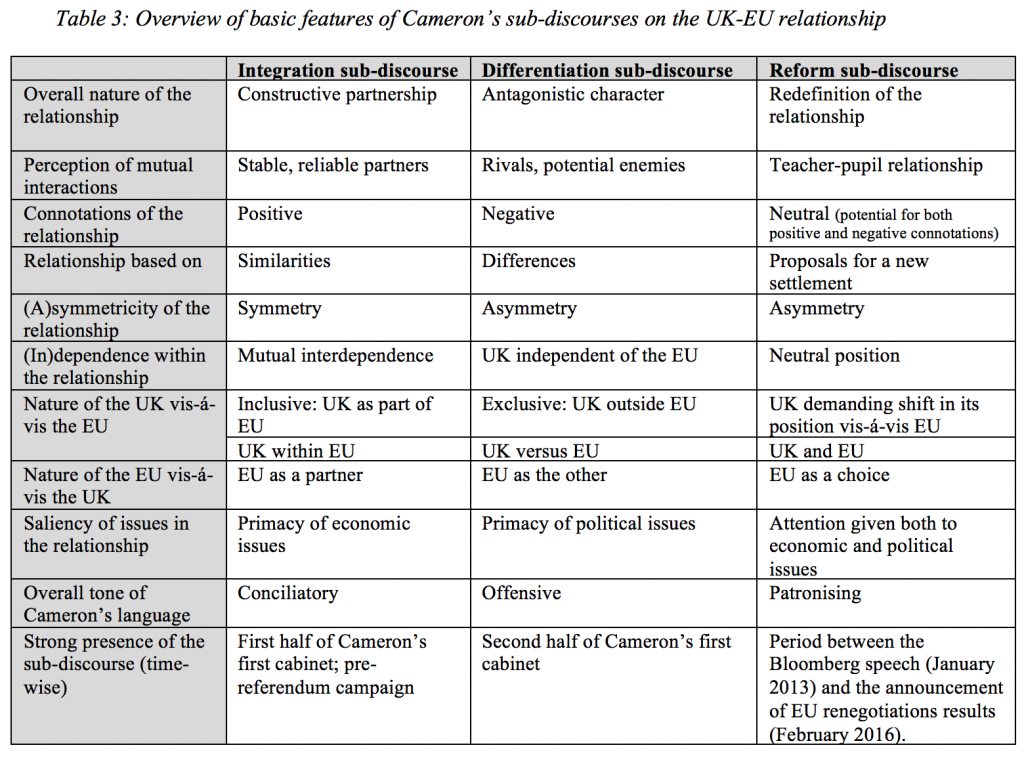

As illustrated by Tables 1 and 2, these sub-discourses substantially differed from each other, both factually and structurally, and also in terms of their main focus. Each possessed unique rhetorical features, used a different vocabulary and highlighted different facets of mutual ties/interactions, therefore producing quite different imaginaries of the UK–EU relationship.

The most positive out of the three was the integration sub-discourse, within which the relationship between the UK and the EU was typically constructed as positive and complementary. Here, Cameron aligned himself with a discursive code that perceived both actors as natural, stable, and reliable partners and framed their interests as complementary. He built bridges between the UK and the EU, accentuated specific multi-level links between them and highlighted the benefits of EU membership. The EU was discursively portrayed here in an inclusive way, with Britain as one of its leading member states

The differentiation sub-discourse pointed in an entirely different direction. Its main tenet was the emphasis on the differences (or even antagonisms) between the UK and the EU and the problematic issues of mutual relations. Cameron frequently deployed the so-called “othering concept”, discursively constructing Britain in opposition to the EU, which was often depicted as an alien body – as a monolith, separate, outward, foreign entity, on the other side of the Channel that was external to Britain and alien to the British way of life. The UK was no longer a member of the EU, but an outsider.

Cameron’s reform sub-discourse was aimed at redefining the status quo – i.e. reforming the existing patterns of the UK–EU relationship. In a recurrent claim of this sub-discourse, Cameron called for a reform of the UK–EU relationship and thereby also of the EU. The desired reform was to modify Britain’s relationship with the EU ‘once and for all’, with Cameron positioning himself into a role of someone with a clear, logical and practical plan to achieve this change.

As can be seen, Cameron’s discourse identities and rhetorical positions vis-à-vis the UK–EU relationship were marked by profound incompatibilities and contradictions, as summarized in Table 3.

The reform sub-discourse was in many respects complementary with, and related to, the other two sub-discourses and could somewhat co-exist with (or be accommodated to) either of them. The differentiation and integration sub-discourses, however, were in many ways polar opposites, displaying elements of serious incompatibility and lying in substantial tension with one another. Parallel usage of such conflicting discourses by the same speaker at the same time might have sent mixed messages to the audience and generated confusion, as exemplified aptly by Cameron’s Bloomberg Speech of January 2013, which has been labelled by a Liberal Democrat politicians as ‘a speech of contradictions’, in which he ‘tried to be all things to all men and managed to fail on every possible count’. In a way, the Bloomberg speech serves as a perfect example of Cameron’s incompatible narratives and rival imaginaries on Britain’s relations with the EU, concentrated in one place.

The EU as a discursive battleground

To conclude, the EU, indeed, proved to be, as Thomas Diez put it, a ‘discursive battleground’ for Cameron. For him, framing the UK–EU relationship was a policy dilemma of the highest order, yet he failed to integrate these largely antithetical sub-discourses into a coherent and politically sustainable discourse on the EU.

In principle, the conflicting patterning of Britain’s relations with the EU closely reproduces the complexity of Cameron’s European agenda. At the same time, it also reflects his attempts to address several audiences simultaneously in a bid to establish the broadest possible coalition of voters and supporters. Most prominently, manoeuvring through and around three largely incompatible discourses mirrors his efforts to reconcile fundamental EU-related tensions within the Conservative Party. Indeed, the ambivalence of Cameron’s discourse stems, in a large part, from his attempts to neutralise an issue that has been one of the most divisive in British contemporary politics. In this sense, it aptly illustrates the long-term struggle of British party leaders and governing elites to manage Europe as well as the country’s troubled accommodation to the EU.

___________

Note: the above draws on the author’s published work in British Politics.

Monika Brusenbauch Meislová is Assistant Professor in the Department of International Relations and European Studies at Masaryk University in the Czech Republic.

Monika Brusenbauch Meislová is Assistant Professor in the Department of International Relations and European Studies at Masaryk University in the Czech Republic.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay/CC0 licence.