Cees van der Eijk and Jonathan Rose estimate the causal effects of the EU referendum on public perceptions of its fairness. They demonstrate that worryingly large groups of citizens have rather dim views of the fairness of electoral processes in the UK.

Cees van der Eijk and Jonathan Rose estimate the causal effects of the EU referendum on public perceptions of its fairness. They demonstrate that worryingly large groups of citizens have rather dim views of the fairness of electoral processes in the UK.

Democracies require – amongst other matters – that their citizens accept the legitimacy of popular verdicts as expressed in elections and referenda. That does not mean that all citizens will be happy about the outcomes; in general, this will not be the case because some have ‘won’ and others have ‘lost’. Yet, the resulting disappointment on the side of the losers should not stand in the way of them recognising the legitimacy of an outcome that is based on the other side(s) having received more support. This ‘loser’s consent’ is necessary for democracy and for peaceful transfers of power after elections, but its existence cannot be taken for granted.

A lively field of research has evolved studying winner-loser effects: differences in regime-supporting attitudes between winners and losers of an election that cannot be attributed to other factors than being on the winning or losing side. The magnitude of any such differences varies across countries and elections, but the direction is almost invariably the same: winners score higher in regime-supporting attitudes than losers. We focus here on beliefs about the fairness of the electoral process, which is of central importance for the legitimacy of electoral results. Differences in this belief between winners and losers reflect, if they cannot be attributed to other factors, that the legitimacy of election outcomes is undermined for those who have lost, and/or that legitimacy in the eyes of the winners merely reflects the fact that they were on the winning side.

The winner-loser literature implies that pronounced winner-loser effects are regrettable because they suggest that support for democracy is not intrinsic but dependent on whether one is or is not on the winning side. However, not all winner-loser differences in perceived fairness are equally relevant in this respect. If, for example, the belief in the fairness of an election is boosted among winners but remains flat among losers, one would be hard pressed to see that as problematic for democracy. If, however, confidence in electoral fairness were to decline not only for the losers of an election but also, perhaps to a smaller degree, for the winners, then that would be more concerning. Most concerning of all would be the combination of a strong boost in confidence in the fairness of an election among the winners combined with a strong decline among the losers. The importance of beliefs about the fairness of elections is not just a matter of abstract academic concern. In the last few months the US came perilously close to a disruption of the peaceful transition of power based on a lie from Trump and his enablers that the election was procedurally unfair and that the result was being ‘stolen’ from them.

In a recently published paper, we studied the beliefs of citizens in Great Britain about the fairness of the conduct of the 2016 referendum about membership of the EU. We did so using data from the British Election Study Internet Panel, a set of repeated surveys with a large sample of citizens. Because many of the interviewees were interviewed repeatedly, we can observe not only their beliefs at a given moment, but also how these beliefs changed over time. We can also compare those who eventually turned out to be winners (the Leave voters) or losers (the Remain voters) at times before the referendum, when they themselves could not yet regard themselves in those terms and track how their beliefs developed thereafter.

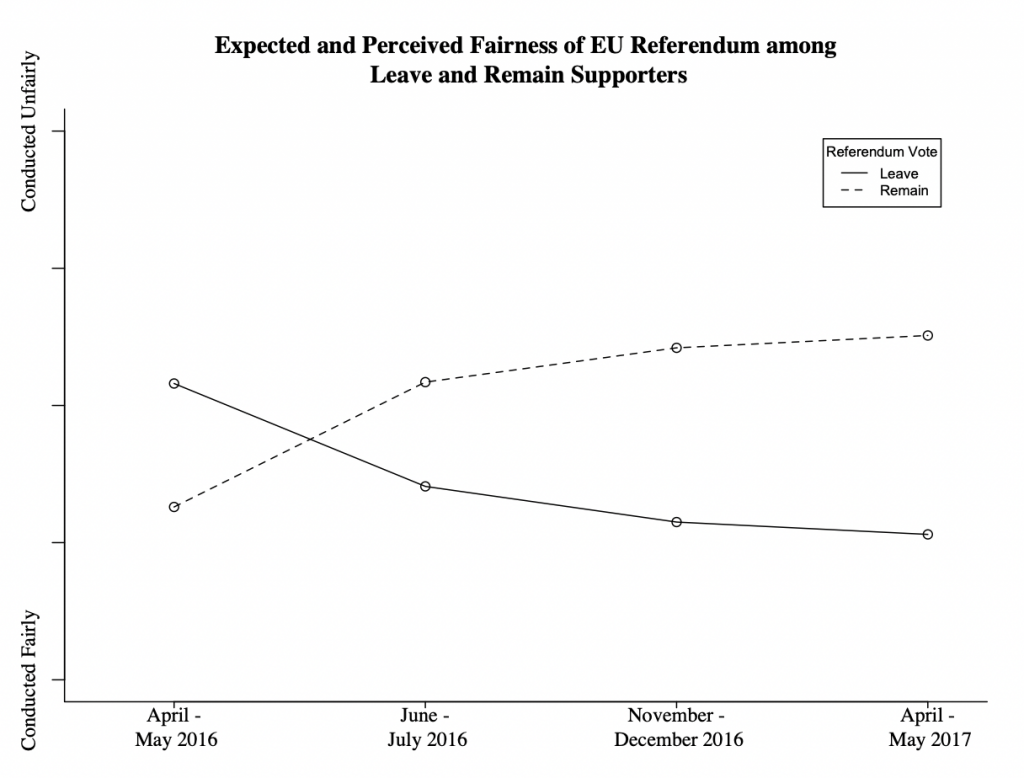

Before the referendum, 44.4% of the respondents expected the referendum to be (very or somewhat) fair, while 30.9% thought it would be (very or somewhat) unfair. Immediately after the referendum, these percentages changed only slightly to 44.2% and 32.5% respectively, while almost a year after the referendum, these percentages were still very similar at 45.8% and 34.6%. The changes in these percentages are in the direction of diminishing confidence in the fairness of the referendum, but they are very small. Yet this appearance of stability is misleading. When distinguishing between those who voted Leave (the winners) and those who voted Remain (the losers) we see very large changes indeed, as visualised in the figure below.

Before the referendum, people who later would vote Leave expressed doubts about its fairness. This is not because of the outcome of the referendum, which had not yet been held, but because – for whatever reasons – they had less trust and confidence in politics. If we express beliefs about the fairness of the referendum on a scale from +2 (very fair) to -2 (very unfair), with 0 reflecting neither fair nor unfair, then the average confidence of fairness before the referendum had been conducted was -0.54 for Leave voters. Remain voters had, on average, a much more positive expectation, scoring +0.28. These beliefs changed considerably after the referendum, to +0.22 for Leave voters and -0.64 for Remain voters. Because these before-after comparisons are based on exactly the same respondents, they can be attributed to what happened in the interval: the referendum itself, and its outcome.

These changes are of an unprecedented magnitude. Moreover, they highlight two key issues. Firstly, they represent a dramatic change from a couple of decades ago and suggest that the increases in contestation of the legitimacy of democratic electoral outcomes is part of a larger trend. As noted above, the aggregate percentage of people who believed that the EU referendum was conducted unfairly was 30.9%, raising to 32.5%, and then to 34.6% a year after the referendum. When the same questions were asked for the 2017 general election 23% saw the election as unfair (before) and 25% (after). While this is lower than for the referendum it is considerably higher than for the 2015 general election, which 16% saw as unfair before it took place, and much higher than a very similar question asked in the BES of 1997 (4%). In short, the referendum may have been bad on this metric, but there is clearly a worrying trend of declining confidence in the fairness of elections.

Secondly, the dramatic winner loser effect observed in the EU referendum is notable because it existed without significant elite contestation. There was no Trump-like figure insisting Remain actually won, and that Leave had hidden votes, stuffed ballot boxes, and rigged counts. Instead, this lack of confidence in the fairness of the process appears to have arisen largely organically from the bottom up, and in its way produced a larger winner-loser effect than has ever been reported in the literature.

The UK’s EU referendum never did result in insurrection or rebellion against the idea of accepting democratic decisions that cut against one’s own desires – but it would be arrogant in the extreme to think that there is not fertile ground for exactly the same kind of problems the US has recently seen. The challenge for public officials the world over is to understand the nature of the problem, and to consider how to build and maintain the losers’ consent.

_____________________

Note: the above draws on the authors’ published work in the British Journal of Politics and International Relations.

Cees van der Eijk is Professor of Social Science Research Methods and Director of the Methods and Data Institute at the University of Nottingham.

Cees van der Eijk is Professor of Social Science Research Methods and Director of the Methods and Data Institute at the University of Nottingham.

Jonathan Rose is Associate Professor in Politics and Research Methodology at De Montfort University.

Jonathan Rose is Associate Professor in Politics and Research Methodology at De Montfort University.

Photo by Hello I’m Nik on Unsplash.