Jill Rutter discusses the state of women’s representation in the upper echelons of the UK civil service, noting that positive developments under the previous government may now be reversing.

Jill Rutter discusses the state of women’s representation in the upper echelons of the UK civil service, noting that positive developments under the previous government may now be reversing.

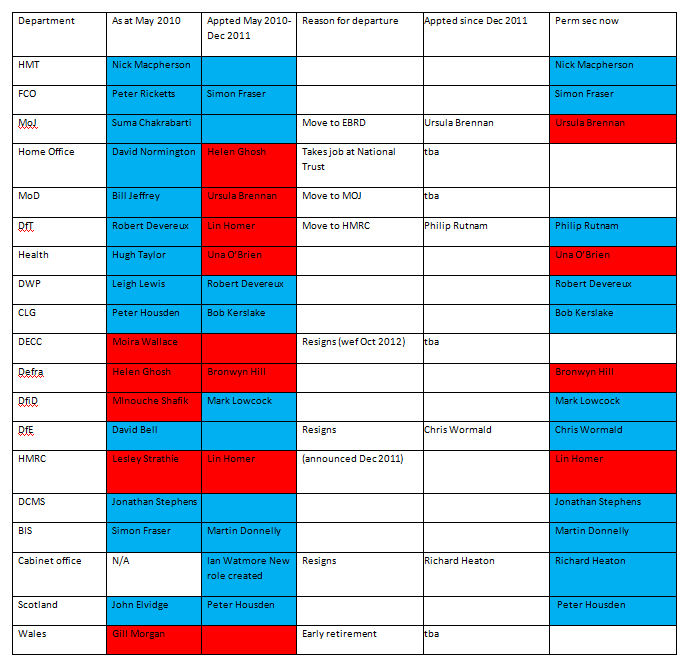

One of Gus O’Donnell’s favourite claims is that under his watch women occupied half of permanent secretary positions. Recent changes suggest that may mark a high point – a point underlined by an appointment and a departure since we first wrote about it.

Gus’s favourite statistic never bore that much scrutiny – in reality there were many more men with the rank of permanent secretary who did not ‘count’ – whether the proliferation of permanent secretaries at the centre or ambassadors with permanent secretary rank. But at one point, some time in early 2011, it was possible to claim that half of the people in charge of government departments were women – and that marked a real change with what had gone before.

But that trend is now reversing. As the above table shows, the last lap of Gus’s reign saw half of new permanent secretary appointments go to women. They took on some of the big spending beasts – not least Ministry of Defence and Health.

But then there was regime change at the top. Despite David Cameron’s early promises, no woman or ethnic minority was deemed to be up to the position of cabinet secretary or head of the home civil service and Gus was replaced by a duumvirate. Since they have been in charge, there have been three promotions to permanent secretary – Philip Rutnam to Transport and Christopher Wormald to Education and, most recently, Richard Heaton has been asked to combine the cabinet office permanent secretary role with his role as first parliamentary counsel. The only move for a woman was the sideways move with the early transfer of Ursula Brennan from Defence to Justice when the only ethnic minority permanent secretary, Suma Chakrabarti, moved on to head up the European Bank of reconstruction and Development. The early retirement of Gill Morgan and the decision by Moira Wallace to stand down as head of DECC in October and, most recently the departure of Helen Ghosh to a ‘dream job’ at the National Trust risks leaving the top of the civil service ‘paler and maler’ than it has been for some time.

There are now four gaps left by departing women. The front-runners for most of those are men.

One of the criticisms of Gus’s changes was that the progress of women at the top was not so well reflected lower down. Whether people decide to enter and stay in the pipeline will depend on signals from the top – both on whether they are likely to be appointed but also make a success of those jobs. So the new leadership of the civil service will not only need to be seen to be championing the cause of people beyond the usual stereotypes to make it to the top of the civil service – but to support them and help them succeed when they get there.

The other point to note is that only two permanent secretaries are still doing the same jobs as when David Cameron entered No.10. The two supreme survivors are the man in charge of the Olympics, who can probably expect a move as his reward, and the one in charge of the economy.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Jill Rutter is Programme Director at the Institute for Government. Jill joined the Institute as a Whitehall secondee in September 2009. Before joining the Institute for Government, Jill was Director of Strategy and Sustainable Development at Defra.