Eve Worth and Christina de Bellaigue develop a new way to account for women’s educational attainments and mobility across the twentieth century, and find that the expansion of educational opportunity for women had more complex effects than a simple comparison of qualifications over time might suggest.

Eve Worth and Christina de Bellaigue develop a new way to account for women’s educational attainments and mobility across the twentieth century, and find that the expansion of educational opportunity for women had more complex effects than a simple comparison of qualifications over time might suggest.

The twentieth century witnessed significant changes in women’s access to education and employment opportunities in Britain. Yet we still need to develop historicised tools and approaches which analyse the impact this had on women’s social mobility and the specificities of this experience. Recent research, particularly qualitative, has shown that education is more important for understanding women’s experience of social mobility than that of men in recent history. This is down to a number of factors, including that women need qualifications as an objective signifier of ability for employers more often than their male counterparts.

Our research develops a new historically contextualised measure of educational attainment across the twentieth century: the Educational Cohort Code (ECC). This code can be fruitfully applied to familial datasets to get a clearer sense of trends within families and the possible influence of family cultures of education and employment on intergenerational mobility. We are also especially interested in how these influences pass down the matrilineal line, an aspect of social mobility which is rarely studied.

Using the ECC, we found that despite the prevalence of narratives of progress and mobility in individual and collective accounts of women’s education across the twentieth century, there were in fact considerable intergenerational continuities in women’s educational attainment across the period. We also found that the expansion of educational opportunities had a differential impact for women and for men; this differentiation destabilises categorisations of class solely based on male occupational hierarchies.

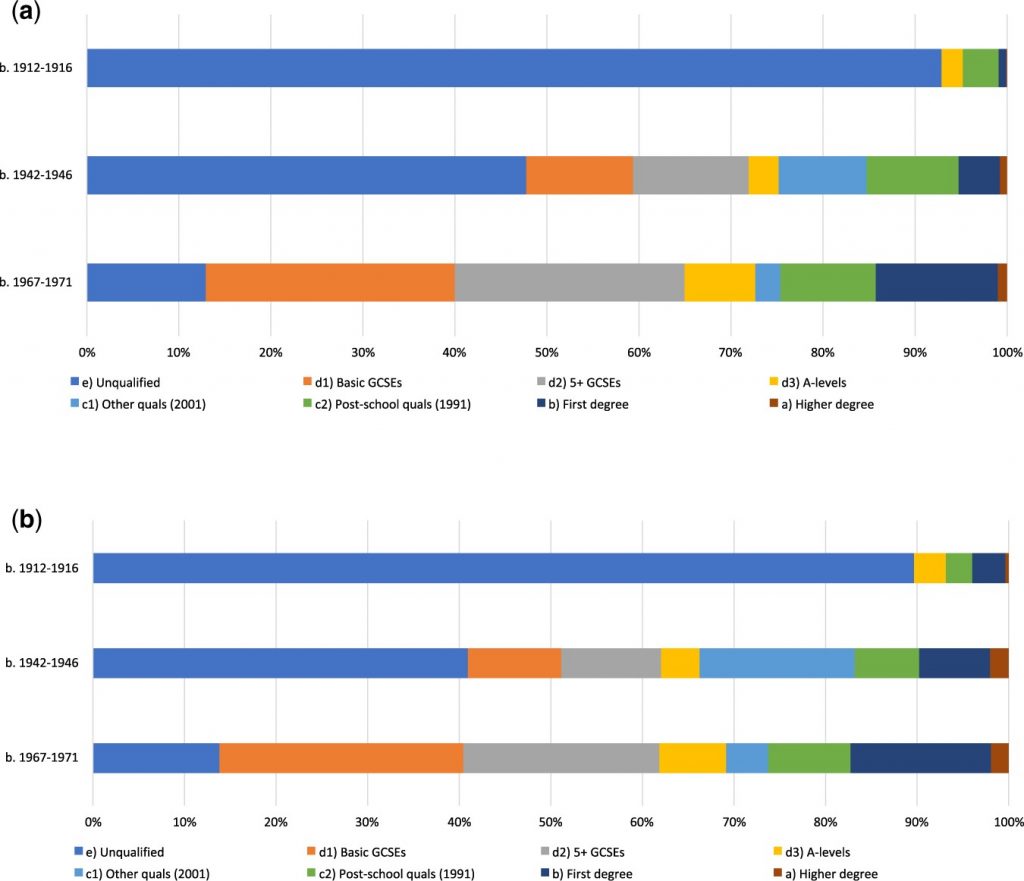

In the first stage of our process, we used the Census of England and Wales to calculate the distribution of highest qualification held by key cohorts of men and women: those born 1912-16, 1942-46, and 1967-71. Figure 1 shows the results of this and the ways in which they differed for men and women. The distribution of qualifications among the general female population changed significantly over the period, even though those obtaining qualifications beyond A-Level or equivalent have remained a minority of the population as a whole. The proportion of women obtaining qualifications of any kind grew over the course of the century but it was from a lower base than their male peers. The types of qualifications obtained also fluctuated across the cohorts. An important example of different gendered patterns of education and training is that the expansion in university education for men occurred earlier than for women. Figure 1 reveals a substantial increase in the proportion of the population securing qualifications. It also suggests, however, that the implications of such qualifications for each generation in relation to their peers would have been substantially different.

Figure 1: Distribution of highest qualification for women (1a) and men (1b) born in the median birth range for each cohort.

We then aimed to assess more precisely the value of these qualifications as positional goods. We were able to translate these distributional patterns into a range that could be applied to analysis of our second dataset: familial information across three generations from the Oxford Biobank (which correspond to our key cohorts). To that end, we calculated the midpoint of the percentage of women securing each qualification-type in each cohort. This generated a figure that could be used to represent the frequency of different educational experiences within each EEC cohort. If we had simply directly compared the qualifications obtained by women over the three generations in most families within the Oxford Biobank dataset, this would suggest a simple upward curve in educational attainment across the generations.

Once we had applied the ECC, however, it was revealed that there is much less clarity in the direction of travel. Instead, there was considerable intergenerational stability in the levels of education secured by the women in most families across the century. To the extent that the twentieth century did see increased relative and long-range upward educational mobility for women, analysing ECC trajectories suggests that this was concentrated in the post-war generation – the first to benefit from compulsory, free secondary education. Indeed, the 1944 Education Act was one of the most significant pieces of legislation passed in twentieth-century Britain. We also identified a significant pattern of interrupted educational trajectories, with a high proportion of women in this cohort attaining their highest qualification as a mature student when the educational landscape changed in the late 1960s.

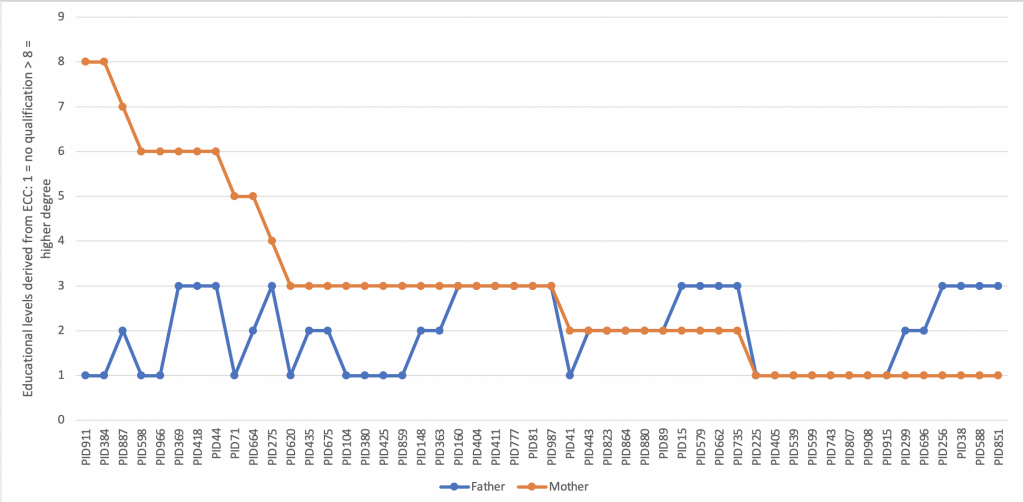

Our sources provide particularly detailed data on the experience of women of the mid-century generation and their educational level compared to their spouses. Figure 2 shows that there was a surprising number of women who were more qualified than their spouses. Of the fifty women married to husbands with no qualifications or with pre-A-Level qualifications only, 21 (42%) were more qualified than their husbands. Discussion of women’s social mobility often centres on marital mobility, suggesting that it was principally through ‘marrying up’ that women might achieve upward social mobility, rather than through their own efforts. Comparing the ECCs of spouses in the Biobank Sample suggests that educational attainment of wives was not always matched by their husbands. One interpretation of this would suggest that, in educational terms at least, marriage might signal downward, rather than upward, mobility.

Figure 2: Highest educational qualification of 50 wives married to husbands with no qualification or limited qualifications (parental cohort).

It is also highly significant that we found that the educational attainments of daughters would echo those of their mothers, and often translated into professional or semi-professional careers (often within the welfare state), rather than those of the fathers, who tended to work either in the trades, in factories, or in business activities. Of the 24 mothers who had a higher ECC than their husbands, 16 (6%) had daughters who then went on to attain a higher ECC than either their mother or their father. The matrilineal line is much more important than previously understood for studying women’s educational mobility.

There are some key implications of our research. Firstly, we need to move away from direct comparisons of educational qualifications and instead develop more historically informed measures. Such measures allow us to detect intergenerational patterns and levels of continuity in educational attainment even during this century of great flux. This finding should encourage policymakers to develop more radical strategies to shift educational continuities. Another implication, clearly impactful in recent history, is the mid-century changes which expanded the state (always key to women’s mobility) and its provision of education at secondary and post-secondary levels. Flexibility in the education system is important for everyone, but especially women. We should also encourage policy interventions which account for women’s mobility in terms of their own endeavours (rather than in marital relationships) and the significance of the matrilineal line in understanding women’s mobility.

____________________

Note: the above draws on the authors’ published work (with Charlotte Bennett, Karin Eli, and Stanley Ulijaszek) in Twentieth Century British History.

Eve Worth is Postdoctoral Fellow in the History of Elites in the Department of Social Policy & Intervention at the University of Oxford.

Eve Worth is Postdoctoral Fellow in the History of Elites in the Department of Social Policy & Intervention at the University of Oxford.

Christina de Bellaigue is Associate Professor of Modern History at Exeter College, University of Oxford.

Christina de Bellaigue is Associate Professor of Modern History at Exeter College, University of Oxford.

Photo by Museums Victoria on Unsplash.