Labor scholars have long advocated social movement unionism as a strategy to revitalize the American labor movement, but how is social movement unionism practiced? Cassandra Engeman exams union participation in the 2006 Los Angeles immigrant rights marches as a case of social movement unionism. She finds that unions allied with large community organizations, preferred reform goals, and advocated tactics perceived as effective. Such strategic decisions were informed by organizational considerations regarding member representation and the long-term capacity for mobilization.

Labor scholars have long advocated social movement unionism as a strategy to revitalize the American labor movement, but how is social movement unionism practiced? Cassandra Engeman exams union participation in the 2006 Los Angeles immigrant rights marches as a case of social movement unionism. She finds that unions allied with large community organizations, preferred reform goals, and advocated tactics perceived as effective. Such strategic decisions were informed by organizational considerations regarding member representation and the long-term capacity for mobilization.

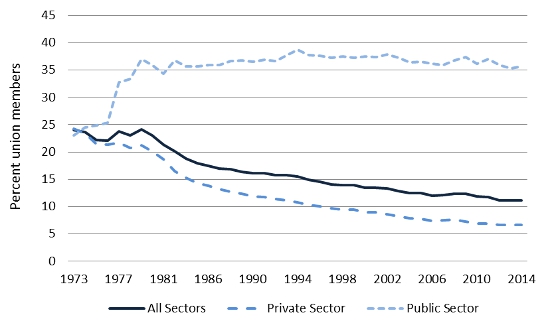

Organized labor in the United States is in the midst of a decades-long decline. This decline is particularly pronounced in the private sector (see Figure 1) with broad-reaching consequences for U.S. workers. According to recent research, the decline in union density – the percent of the workforce who are union members – explains much of the rise in income inequality and working poverty in the U.S.

Figure 1 – Decline in union density in the United States, 1973-2014.

Source: Hirsch BT, MacPherson DA (2003).

Contending with this decline and its consequences, labor researchers have prescribed social movement unionism (SMU) as a way to build union political and organizational strength. Given the importance of SMU to union revitalization, I wanted to know how it works. However, the concept of SMU as applied in existing research suffers from ambiguity, having been used to describe activity ranging from direct action tactics to traditional union organizing of marginalized groups of workers.

Additionally, SMU is often offered as antithesis and antidote to business unionism. A term that is similarly vague, business unionism can describe top-down organizing efforts or corruption. It can also describe apolitical, short-sited strategy that focuses only on contract negotiations and enforcement – basic organizational functions of a union. When juxtaposed with business unionism, SMU risks masking organizational structures that social movement scholars have found important to understanding movement strategies and outcomes.

To understand how unions practice SMU, I examined union participation in the 2006 immigrant rights marches in Los Angeles. By participating in the marches, unions exhibited two characteristics of SMU that are consistent across applications: (1) alliance with other community organizations, and (2) adoption of goals outside of traditional collective bargaining and contract enforcement.

The primary focus of the 2006 marches was to protest a bill that passed the U.S. House of Representatives on December 16, 2005. This bill (HR 4437) included the construction of a 700-mile fence along the U.S.-Mexico border and criminalization of undocumented immigration and aid to undocumented immigrants, thus implicating service-providing organizations, such as churches and nonprofits.

These marches were among the largest in U.S. history. The first march on March 25th drew more than 500,000 participants, and the march on May 1st (May Day/International Workers’ Day) drew 650,000. Labor unions were among the organizers, providing security for the marches, activating established networks for mobilization, and building on the marches’ momentum for political impact in subsequent U.S. elections.

By Jonathan McIntosh (Own work) [CC BY 2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons

Two months after the marches, I began interviewing participants from two coalitions responsible for organizing them: the March 25th Coalition (M25C) and the We Are America Coalition (WAAC). Though union representatives were involved in each, the WAAC included official participation of several prominent labor organizations while the M25C included individual activists or staff organizers from three unions.

Comparing the coalitions, I found that unions allied with large community organizations, preferred reform goals, and advocated tactics perceived as effective. The WAAC, with official members from organized labor and other large community organizations, supported parallel legislation introduced in the Senate in 2006 (S 2611). Though many in the WAAC noted the bill was not ideal, they felt that it would make needed improvements and had a much greater chance of passing a Republican Congress than full amnesty, which was the legislative goal of the M25C.

The two coalitions also differed in preferred tactics. The M25C announced a boycott and strike on May 1, 2006. The WAAC declined to endorse a boycott or strike and organized a separate march – though the marches converged that afternoon in united protest. In their decision not to call a boycott and strike, WAAC members expressed concern about unintended consequences of workers being fired or disciplined for participation. Decisions about goals and tactics were influenced by the need to maintain credibility among members, because an unsuccessful strike or policy reform – resulting in losses, little or no change, or other unintended consequences – could damage an organization’s credibility and subsequent ability to mobilize.

SMU advocates argue that unions should engage in the practice, because it builds credibility among new groups of workers, enabling organizing and thus revitalization. While concerns about credibility influenced strategies, it was neither a motivation for SMU nor the only justification for winning reforms, however incremental. Rather, achieving concrete improvements in people’s lives was of deep personal importance to union leaders. All of the union staff and elected leaders interviewed for this study identified as Latina/o or Chicana/o and described their commitment to union organizing and immigrant rights as rooted in their personal family and activist histories.

The long-term impacts of the 2006 immigrant rights marches are still being assessed. Though the marches initially put HR 4437 to rest, they were followed by stalled progress on immigration reform and increased deportations. However, the marches also signified a potentially powerful reunification of immigrant civic engagement and labor rights struggles in the U.S. that could advance progressive politics. Although Congress has yet to pass immigration reform, it remains at the forefront of legislative agendas.

The efficacy of SMU is not yet fully understood, and some labor scholars have questioned its use as a universal mechanism for union revitalization. While trade union leaders collectively bargain through legislative changes, there are growing threats to its organizational existence – most recently from a looming Supreme Court decision that may severely limit unions’ capacity to represent workers in relation to employers and policymakers. In this unfavorable political context, it is important to remember that the power of organized labor remains rooted in its location in the economic system.

However, the concept of SMU, despite its problems, brings deserving attention to union social movement activity, which is important to the vitality of organized labor and particularly important for social change as unions remain the strongest organizational representatives of workers in public policy debates.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Social movement unionism in practice: organizational dimensions of union mobilization in the Los Angeles immigrant rights marches’, in Work, employment and society.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1OMMN5M

_________________________________

Cassandra Engeman – University of California, Santa Barbara and the WZB Social Science Research Center in Berlin

Cassandra Engeman – University of California, Santa Barbara and the WZB Social Science Research Center in Berlin

Cassandra Engeman is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara and a visiting researcher at the WZB Social Science Research Center in Berlin. Her overall research interests center on the strategies and outcomes of social movement organizations, particularly organized labor and its impacts on social policies governing the workplace. Her dissertation examines organized labor’s influence on U.S. state legislation regarding family leave, maternity/parental leave, and paid sick days.