For many, democracy is at the cornerstone of the United States, and yet in many Southern states, voter suppression occurs in election after election. In new research, Brad Epperly finds that in the pre-Jim Crow era, lynchings were much more likely in the lead up to an election, and that this relationship disappeared once Jim Crow laws were in place: Southern politicians had replaced violence aimed at suppressing black voters with laws which would have the same effect. While these laws fell away following the Civil Rights Era, with the recent rolling back of much of the Voting Rights Act, he argues, we are now seeing a return to legal means for voter suppression.

For many, democracy is at the cornerstone of the United States, and yet in many Southern states, voter suppression occurs in election after election. In new research, Brad Epperly finds that in the pre-Jim Crow era, lynchings were much more likely in the lead up to an election, and that this relationship disappeared once Jim Crow laws were in place: Southern politicians had replaced violence aimed at suppressing black voters with laws which would have the same effect. While these laws fell away following the Civil Rights Era, with the recent rolling back of much of the Voting Rights Act, he argues, we are now seeing a return to legal means for voter suppression.

The question of who votes is central to democratic politics. For obvious reasons, political parties want their supporters to show up on Election Day, which is why many spend significant time and resources on get out the vote operations. Just as obviously, it helps a party if more of their opponents’ supporters don’t go to the polls.

As a result, parties in government have sometimes attempted to suppress voting by their opponents. Broadly, governments prefer to use centralized, legal approaches to suppress voting by, for example, passing laws that make it harder for their opponents to vote. Laws have the benefit of usually being followed, are by definition “legal”, and are usually reliably enforced by bureaucratic agents of the state, such as the police. But sometimes governments do not have the internal political capacity to enact such laws or the bureaucratic capacity to implement them. Further, sometimes external actors, like international organizations or central governments in federalist systems, prevent such laws from being enacted. In these instances, parties can turn to decentralized, ad hoc approaches to voter suppression. This is less effective and can provoke backlash because it has a greater potential to turn violent. If governments prefer centralized voter suppression, we should see that when this becomes an option because constraints are removed then they will quickly transition to centralized, legal approaches to voter suppression.

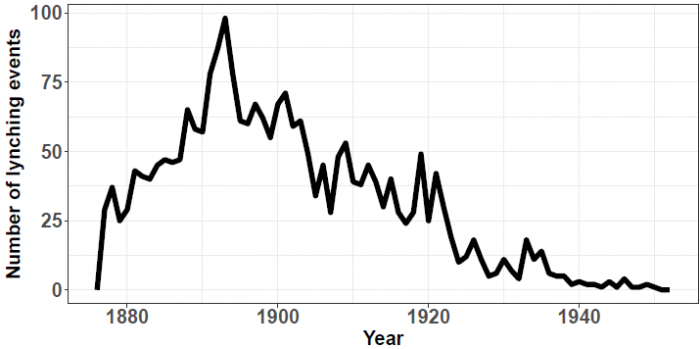

Our analysis examines the “era of lynching” that took place in the more than half century after 1877, when the federal government ended the policy of Reconstruction, whereby federal power and troops were used (with varying degrees of effectiveness) to protect the rights of newly-free black citizens in the South. Figure 1 shows the yearly count of lynching events during this era. While we do not think that lynching was the only form of violence used to suppress African American voting, given its especially brutal nature it is the most important. And, unlike common forms of more restrained violence, given its extremely public nature, high-quality records of lynchings exist.

Figure 1 – Lynching events in the American South, 1870-1955

White Southern elites, represented by the Democratic Party, did all they could to “persuade” African Americans note to vote. An election plan from 1876 stated that, “Every Democrat must feel honor bound to control the vote of at least one negro, by intimidation, purchase, keeping him away or as each individual may determine, how he may best accomplish it.” While observers at the time such as Ida B. Wells recognized that lynchings were in part a way to terrorize potential black voters, social scientists studying lynching have been less certain. In their exhaustive book A Festival of Violence, Stewart Tolnay and E.M. Beck assess a diverse array of possible causes of lynchings, concluding that there is little evidence for the “political threat” hypothesis.

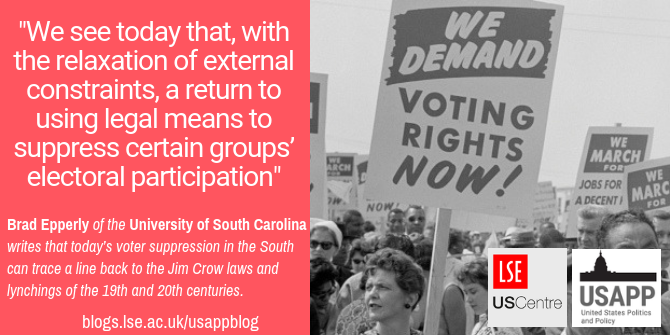

Marchers with signs at the March on Washington, 1963 Credit: Library of Congress

We argue, however, that the political threat posed by African Americans in the South was in many ways an electoral threat, and that recognizing this has three implications: when, where, and under what conditions the elections are held should affect the propensity for election-related violence. When elections occur is important because violence used to suppress voting should occur in the run-up to elections. Where elections occur is important because support for the Democratic Party was not monolithic in the South at this time. Under what conditions is important because the logic of using violence to suppress voting no longer matters if the electoral threat posed by black electoral participation is removed via Jim Crow laws—like grandfather clauses and literacy tests–that disenfranchise these very voters.

To test these ideas, we use county-level data to assess the relationship between lynching and elections across 11 Southern states, both before and after the implementation of Jim Crow. Specifically, we test whether the number of days until an election occurs and the competitiveness of the county are effective predictors of whether a lynching event took place in that county. If we are correct that (some) lynchings were attempts to suppression black electoral participation, both factors should be associated with lynchings, but only before Jim Crow goes into effect.

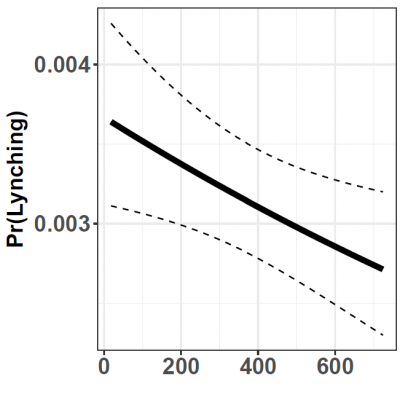

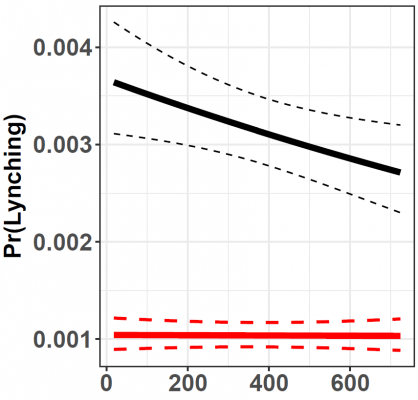

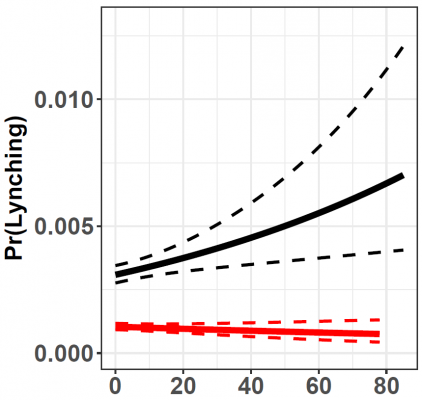

Plots A and B in Figure 2 visualize the results of our analyses for the years before Jim Crow policies were in effect, with each showing the predicted probability of a lynching event occurring at different levels of these two political variables. Plot A shows that as the number of days until the next election increases, the likelihood of lynching falls. When an election is about to occur, however, lynchings are 25 percent more likely than when they are years distant. Plot B in Figure 2 shows the share of the vote garnered by the Populist Party, which during this era posed the greatest electoral threat to Democratic power in the South. Here we see that lynchings were far more likely in those counties where the Populist Party posed a greater threat to the Democrats’ power.

Figure 2 – Pre-Jim Crow likelihood of lynchings

Plot A – Likelihood of lynchings and days before next election

Plot B – Likelihood of lynchings and Populist vote share

But do these links between politics and violence hold once the electoral threat black voters pose to Democratic power is neutralized? Figure 3 reproduces Figure 2; this time including the effects of these factors after Jim Crow is in place. These are the red lines. Put simply: after Jim Crow is in place, the political factors that are previously associated with lynching don’t matter at all. The lines are flat: no matter the days to election or Populist vote share, the likelihood a lynching occurs is unchanged. Law replaces the need for violence.

Figure 3 – Likelihood of lynchings before and after introduction of Jim Crow laws

Plot A – Likelihood of lynchings and days before next election

Plot B – Likelihood of lynchings and Populist vote share

Using the law to minimize the electoral impact of certain types of voters is not always available. It was not available during Reconstruction, for example, because Democrats lacked unilateral control over the levers of power in Southern states. And for a decade and a half afterwards, the threat of a return to federal intervention inhibited the full “Redemption” of the South. Similarly, it was external constraints that led to the demise of legalized disenfranchisement, with a return of federal interest in and commitment to the civil and political rights of African Americans in the South during the Civil Rights Era (known to some as the “Second Reconstruction”).

Although this era did see a spasm of violence, including electoral violence, a return to widespread use of violence to suppress black electoral participation did not occur. And for decades after, external constraints curtailed the use of law to suppress black voting; namely, the Voting Rights Act and federal judicial decision-making made attempts to use laws for voter suppression ineffective. These external constraints are, however, no longer as robust as they once were. In 2013 the Supreme Court gutted a core part of the Voting Rights Act, and many attempts to make it harder for poor and minority voters to exercise their suffrage rights have been upheld by federal courts. As a result, in the past decade 25 states (overwhelmingly Republican-controlled) have made it more difficult to vote, especially in ways that particularly affect poor and minority voters (which are more likely to favor Democrats).

We started from the premise that, when possible, parties like to make it more difficult for groups that support their opponents to vote. While this unhappy phenomenon is not restricted to the South (even while implementing Reconstruction in the South, northern Republicans were making it more difficult for immigrants in urban areas to vote), it is in the South that the greatest reversal of enfranchisement in history occurred. But Jim Crow laws that disenfranchised Southern blacks did not arise out of nowhere. In the decades before it became possible to use laws to suppress voting, white Democrats in the South used violence. We see today that, with the relaxation of external constraints, a return to using legal means to suppress certain groups’ electoral participation. That these means are neither as systematic nor successful as the disenfranchisement strategies used a century ago does not mean they are not driven by similar factors, or fundamental attacks on democratic participation.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Rule by Violence, Rule by Law: Lynching, Jim Crow, and the Continuing Evolution of Voter Suppression in the U.S.’, in Perspectives on Politics.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2HL6uQp

About the author

Brad Epperly – University of South Carolina

Brad Epperly – University of South Carolina

Brad Epperly is Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of South Carolina. His research focuses on the rule of law, especially judicial institutions.