US state governments maintain dedicated units aimed at detecting fraud in welfare services like SNAP. Spencer Headworth writes that these units solicit voluntary informants and co-opt neutral and positive social ties between people to find out about potential fraud. He argues that taking advantage of social ties in this way can undermine or even destroy the very relationships between vulnerable people that help them to persevere under difficult circumstances.

US state governments maintain dedicated units aimed at detecting fraud in welfare services like SNAP. Spencer Headworth writes that these units solicit voluntary informants and co-opt neutral and positive social ties between people to find out about potential fraud. He argues that taking advantage of social ties in this way can undermine or even destroy the very relationships between vulnerable people that help them to persevere under difficult circumstances.

Welfare programs have long included surveillance and punishment. In the United States, federal law requires state governments to maintain dedicated fraud control units aimed at detecting and substantiating welfare recipients’ violations of program rules; in 2016, state-level agencies undertook nearly one million SNAP client fraud investigations. These welfare fraud units are a leading example of how areas of government that have been historically oriented towards support and assistance are now increasingly integrated with the criminal justice system, including welfare offices and other sites of social service provision. Investigators gain some evidence through willing cooperation, when people voluntarily implicate others. Other times, investigators co-opt neutral or positive social ties for enforcement purposes. Repurposing welfare clients’ social ties for fraud enforcement presents a two-fold threat to subsistence and social mobility prospects: it imposes punishments—including ending benefits—while at the same time damaging social support networks.

The harm resulting from cutting off support and other forms of punishment for rule violations is clear. Less obvious—and more insidious—is the harm resulting from appropriating social ties on the way to these punishments. Social ties are critical to many poor Americans’ subsistence. But appropriation reveals how the very forms of cooperation that support perseverance under adverse circumstances can also expose people to hazards. Repurposing social ties to remove one component of the survival calculus is not just paradoxical: it is doubly harmful, as using people’s connections against them undermines relationships and foments enmity, exacerbating formal social control’s damage to disadvantaged communities’ social solidarity. Enforcement methods based on turning clients’ relationships against them compound the stressors of poverty, erode trust, and threaten networks of social support and cohesion.

Agencies and individual street-level bureaucrats have incentives to find incriminating information about clients, in their social ties and elsewhere: states are allowed to retain 35 percent of the federal SNAP benefit dollars they recover via fraud actions, as well as 20 percent of recovered overpayments not substantiated as intentionally fraudulent, and fraud workers’ individual performance evaluations hinge on completed case numbers. These incentives show how government priorities drive this form of social tie appropriation.

How welfare fraud units encourage voluntary cooperation

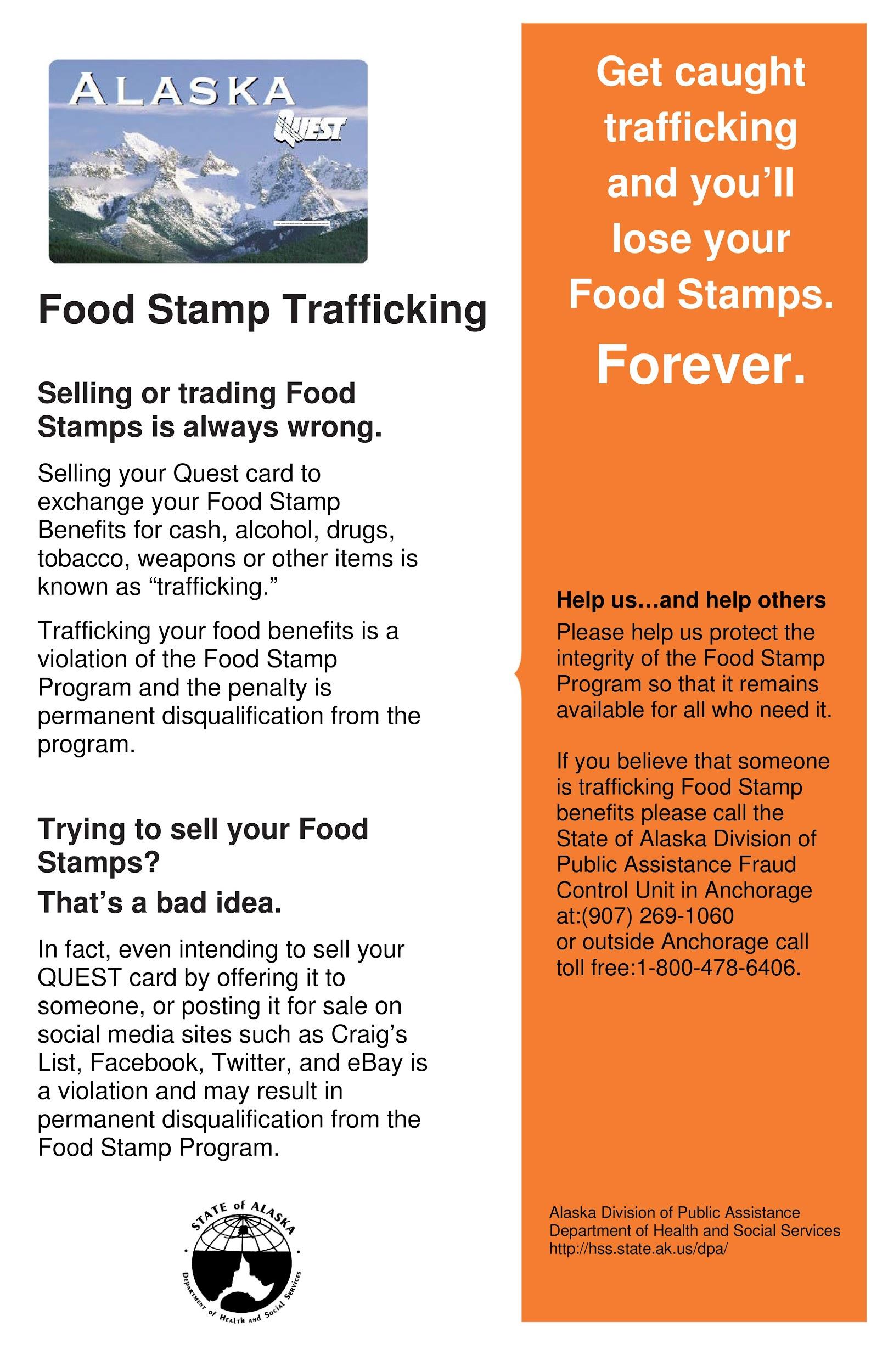

Investigators use different strategies to appropriate clients’ social ties. Some clients’ associates cooperate willingly, volunteering their fraud suspicions to agencies. This kind of cooperation hinges on comparatively weak informant–suspect loyalty, which may reflect weaker ties lacking emotional intensity, or ties of varying strength with negative associations. Fraud units actively encourage voluntary cooperation—Florida even offers cash rewards for informing. Occasionally, they solicit tips on billboards or public transit advertisements. More often they directly target client and applicant populations. Local offices and administration buildings display fraud-centered flyers and pamphlets like the example shown in Figure 1, and agency websites detail welfare fraud and ways to report it. States offer a bevy of fraud reporting methods: phone, fax, online form, email, and conventional mail, as well as in-person reports to local offices. Some notices juxtapose warnings about penalties for committing fraud with exhortations to report others’ suspected rule-breaking. Nearly all highlight fraud’s seriousness and the penalties for substantiated allegations. These solicitations put the state’s coercive power on offer.

Figure 1- Sample Fraud Flyer (Alaska)

Fraud workers overwhelmingly believe that personal motivations underlie voluntary cooperation. This consensus transcends differences of race, gender, geographic location, and broader attitudes about programs and clients. As fraud workers see it, fraud reporting can offer friends, relatives, co-workers, neighbors, or former or current lovers an instrument for personal agendas or a weapon in interpersonal conflicts.

Appropriating neutral and positive social ties

Agency-initiated appropriation of clients’ social ties—or co-optation—occurs in different circumstances, allowing access to relationships with potentially stronger loyalty sentiments. In its direct form, best represented in investigator-initiated field interviews with suspects’ associates, co-optation involves greater subterfuge, with investigators emphasizing their association with the larger public welfare system rather than its dedicated enforcement function. Skillful investigators can tease out information from neighbors and other people familiar with clients without ever indicating exactly what they are trying to establish, or even revealing the enforcement-specific nature of their work.

Photo by Matthew Henry on Unsplash

Strong ties are likely to contain personal information that is adaptable to fraud investigators’ purposes, but the loyalty associated with such ties can impede outsiders’ access. “Just talking”-style tactics provide investigators one avenue around the stronger loyalty sentiments they expect to encounter when attempting agency-initiated co-optation. Investigators seek out people whose relational and residential positions offer access to fraud suspects’ home lives and personal affairs. In the absence of motivation to voluntarily inform, tactics for accessing these relationships hinge on subterfuge and selective self-presentation.

Using social media to investigate fraud

Co-opting ties via online social networking systems, on the other hand, drops investigative visibility to zero. Investigators are covert when accessing information from suspects’ online social networks. Thus, they need not emphasize any aspect of their position, and loyalty sentiments do not apply. Fraud workers across the country routinely pull incriminating information from clients’ online profiles. Investigators sometimes catch attempts to sell SNAP benefits on Craigslist or other sites. Most commonly, however, they gather information about household circumstances through what clients reveal in publicly visible Facebook posts. There are few better sources of adaptable personal information than clients themselves, provided they unwittingly facilitate access through posting relevant material online.

Depending on the situation, social media posts may just be a lead to be followed up and confirmed via other sources, or a printout might be presented directly to an administrative hearing officer as evidence of rule-breaking. Inadvertent revelations can also provide pathways to confessions. Some investigators report using records of Facebook posts to elicit admissions from clients, describing the ability to confront people with their own statements as an effective technique for overcoming resistance and extracting acknowledgment of rule violation. Online network co-optation demonstrates fraud investigation’s embrace of “the new surveillance,” “scrutiny of individuals, groups, and contexts through the use of technical means to extract or create information”. Like their “real world” social ties, clients’ online social networking creates unanticipated vulnerabilities.

Turning the personal into the penal

Fraud units are fundamentally engaged in the pursuit of information regarding the most intimate aspects of people’s lives. To substantiate charges, investigators endeavor to ascertain and substantiate where people live, how they access resources, and with whom they share their beds. The fraud enforcement process thus converts the personal into the penal. The general loss of privacy associated with program participation becomes decidedly punitive when the most intimate details of a person’s life are not only subject to exposure and scrutiny, but turned around and used to substantiate a punishable offense.

Exploiting personal grievances provides investigators a recruiting pipeline for voluntary informants. Subterfuge provides opportunities to collect damaging information from the unwitting, including clients’ associates and clients themselves in their online social networking activities. Together, these tactics change adaptable private knowledge into state knowledge, and the content of daily social life into the currency of formal social control.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Getting to Know You: Welfare Fraud Investigation and the Appropriation of Social Ties’, in the American Sociological Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2F4RAml

About the author

Spencer Headworth – Purdue University

Spencer Headworth – Purdue University

Spencer Headworth is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Purdue University and an Affiliated Scholar of the American Bar Foundation. His research on crime, social control, inequality, law, professions, and organizations has appeared in American Sociological Review, Social Forces, DuBois Review, and other venues. He is currently completing his first monograph, on welfare fraud investigation in the United States. The author thanks Sheriff Almakki for outstanding research assistance in preparing this essay.