One of the generally accepted truisms of US politics is that the party which holds the White House tends to lose seats in midterm elections. This maxim has developed within a dynamic and multilevel election system. With the 2022 midterms just over the horizon, Peter Finn explores if the incumbent Democrats will be able to break with electoral tradition and maintain control of the US House and Senate.

One of the generally accepted truisms of US politics is that the party which holds the White House tends to lose seats in midterm elections. This maxim has developed within a dynamic and multilevel election system. With the 2022 midterms just over the horizon, Peter Finn explores if the incumbent Democrats will be able to break with electoral tradition and maintain control of the US House and Senate.

- Looking ahead to elections across the US in 2022, our mini-series, ‘The 2022 midterms‘, explores aspects of elections at the presidential, Senate, House of Representative and state levels, and also reflects on what the results will mean for US politics moving forward. If you are interested in contributing, please contact Rob Ledger (ledger@em.uni-frankfurt.de) or Peter Finn (p.finn@kingston.ac.uk).

The US’ dynamic multilevel election system(s)

The US electoral system is complex. Perhaps more accurately described as a multilevel collection of interrelated and interconnected subsystems, the overarching electoral infrastructure within the system manages elections at federal, state, and city/local levels across 50 States plus Washington D.C. and the US’s overseas territories.

Each state, Washington D.C., and territory has at least two-party level subsystems within the Republican and Democratic parties that interact with formal state electoral systems in divergent ways in different states. We can also add smaller parties such as the Greens and the Libertarians into this mix.

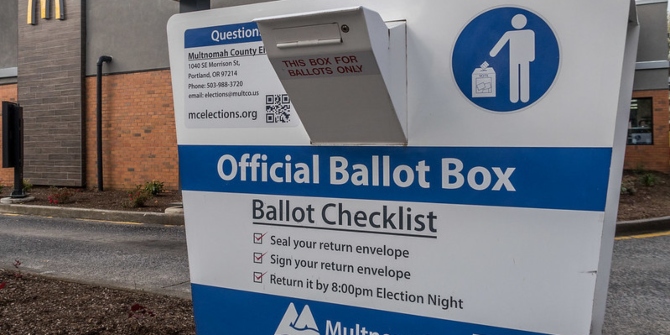

Adding to this complexity is the fact that the overarching system is constantly evolving, with the way elections are run continually being tweaked. These tweaks are often the site of partisan battles, with access to voting, for instance, being a continual point of contestation. Moreover, each decade the boundaries that define electoral districts are redrawn to reflect demographic changes in processes that differ between states.

In short then, even for a seasoned observer, the complexity of the US electoral system, especially when combined with the fact it is ever changing, can make it hard to track.

Photo by Daniele Franchi on Unsplash

The US Electoral Cycle

Within the US electoral system there are procedural electoral cycles that help define how candidates and parties operate within the system. At a federal level these cycles are predictable and, special elections that can periodically arise for seats in the House of Representatives and the Senate aside, occur on a fixed timetable: with the presidency up for grabs every four years, all 435 members of the House of Representatives up for re-election every two years, and a third of the 100 Senators up for re-election every two years in a rolling cycle that sees individual senators serve six-year terms.

At a state, Washington D.C., and overseas territory level, however, there is a great deal of variety, with subsystems at this level slotting into the national cycle in the terms of providing candidates for House of Representative and Senate elections (though not in Washington D.C. or in overseas territories) and feeding into presidential nominations via primaries and, to a lesser extent, caucuses. The way these primaries and caucuses operate varies from state to state and within and between political parties.

Electoral cycles for state and local level posts can operate to timetables outside of the core presidential and midterm federal cycle, with so-called off year elections occurring for regularly scheduled gubernatorial (Governor) elections in New Jersey and Virginia in November 2021, for instance.

As such, rather than there being a single electoral cycle, it would be fairer to say that there are dozens of sub cycles all feeding into the overarching national electoral cycle in differing ways. Within each state, Washington D.C., and overseas territory divergent timetables for state and local elections feed into the federal cycle in different ways.

Midterms

It is a broadly accepted truism that the party of a US president will generally lose seats in midterm elections. Indeed, when the impact of such cycles are particularly strong, they are referred to as wave elections. One only has to look at Republican losses in 2018 when Trump was president (though the Republicans did gain Senate seats) and both Obama administrations to see why this truism has gained traction as an accepted feature of US politics. As such, the result of previous election cycles (and the party whose candidate was elected to the White House) appear to feed into midterm elections by negatively impacting the party of the president at the next set of elections.

It would, however, be untrue to say that predetermined swings against the party holding the White House are the sole decider of midterm elections. Instead, it is incumbent on opposition parties to make electoral hay in a potentially favourable climate. Whilst the party already in power, whether just in charge of the presidency, also controlling either the House of Representatives or the Senate, or holding the trifecta of all three, must either positively defend their record or make a negative case for what will happen should they lose seats. Another line of campaigning is for the party that does not hold the White House to caution against what will happen if the party of the president is not checked. In varying ways, such messaging has played out in previous midterms. In 2010, for example, Republicans campaigned against the health care reforms passed by the Obama administration. While eight years later Democrats campaigned heavily on the fear that, should a Trump led Republican party do well in the 2018 Midterms, then the same health reforms would be under threat.

The 2022 Midterms

So where does all this leave us for the 2022 midterms? Is a swing away from the Democrats, who currently (just about, and via the ability of Vice President Kamala Harris to cast a deciding vote in an evenly split Senate, hold the federal trifecta) inevitable, or can they leverage infrastructure spending and a degree of bi-partisanship, and use a fear of Trump influenced Republican policies, to sufficiently influence Democrat leaning independents to give them another two years of unified control? Conversely, will a Republican message crafted around attacking Democrats and appealing to a base seemingly still in thrall to Trump be able to gain seats in both houses of congress, or will these messages fall flat beyond their core supporters and, thus, replicate the status quo?

In January I co-wrote that three major issues that could influence the 2022 midterms were COVID-19, Trump, and the economy. One could now perhaps add the War in Ukraine (though how this may occur is likely complex) and the debates around abortion and (likely) gun control. Yet, though the most important date in the current electoral cycle is clearly Tuesday 8th November 2022, the candidates that will be standing on that date are currently being decided in a primary season being influenced by these issues, with these influences playing out in different ways in different states. As such, both Republicans and Democrats will be manoeuvring to gain advantages within the US’s multilevel election system to ensure they are best placed to benefit from the electoral and political cycles occurring within it.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3O4SHn9

About the author

Peter Finn – Kingston University

Peter Finn – Kingston University

Dr Peter Finn is a multi-award-winning Senior Lecturer in Politics at Kingston University. His research is focused on conceptualising the ways that the US and the UK attempt to embed impunity for violations of international law into their national security operations. He is also interested in US politics more generally, with a particular focus on presidential power and elections. He has, among other places, been featured in The Guardian, The Conversation, Open Democracy and Critical Military Studies.