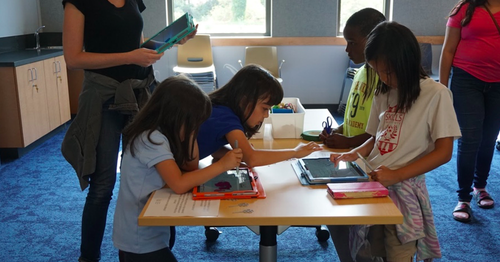

How much is too much when it comes to ‘screen time’? Sonia Livingstone and Alicia Blum-Ross round-up the advice that is being given to parents about screen time rules, where reports represent advice on a scale from fear to hype. Rather than measuring screentime purely by the clock, Alicia and Sonia suggest a set of lifestyle-based questions that can help moderate our interpretation of screentime’s benefits and risks. Sonia is Professor of Social Psychology at LSE’s Department of Media and Communications and is the lead investigator of the Parenting for a Digital Future research project. Alicia is a researcher at the LSE’s Department of Media and Communications, and in addition to her work on the Parenting for a Digital Future research project she is interested in youth media production. [Header image credit: D. Nguyen, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0]

How much is too much when it comes to ‘screen time’? Sonia Livingstone and Alicia Blum-Ross round-up the advice that is being given to parents about screen time rules, where reports represent advice on a scale from fear to hype. Rather than measuring screentime purely by the clock, Alicia and Sonia suggest a set of lifestyle-based questions that can help moderate our interpretation of screentime’s benefits and risks. Sonia is Professor of Social Psychology at LSE’s Department of Media and Communications and is the lead investigator of the Parenting for a Digital Future research project. Alicia is a researcher at the LSE’s Department of Media and Communications, and in addition to her work on the Parenting for a Digital Future research project she is interested in youth media production. [Header image credit: D. Nguyen, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0]

‘Screen time’, as ever, is a hot topic for academics, policy folk and for parents. There’s a seemingly endless debate about how much is too much, or indeed (as we’ve argued) whether ‘time’ is really the right frame at all.

We were inspired to take up the screen time debate on this blog for two reasons:

- First, because in our research, we listened over and over again to British parents referencing some version of the famous American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) 2×2 rules (no screen time under 2, only 2 hours a day for kids 2 and above), even if they usually had no idea where this came from.

- Second, because we knew that the AAP was about to update these guidelines (announced in October 2016) to recognize the changes in the family media landscape, and that these guidelines would be influential to parents far beyond U.S. borders.

What worried us was that parents seemed to use these rules as a rod with which to beat themselves, worrying how much was too much, whether family TV time or homework ‘counts’ as screen time, or feeling guilty or inadequate as parents when their children watched ‘too much’. Yet, such rules just didn’t seem realistic in this ‘digital age’ when homework, shopping, Skyping with grandparents elsewhere or fathers working away from home.

So, we scoured the internet, and wrote to experts, to discover what advice is being given to parents. We uncovered quite a hodgepodge of advice, not always evidence-based, generally negative in intending to reduce exposure to ‘harmful’ media, and remarkably little of it able to recognize that parents are acquiring digital media at home to enable positive benefits for their children and, furthermore, they are often quite skilled in understanding it, not always being the ‘digital immigrants’ of old. Too much implies comfortable middle-class homes and fails to recognize the constraints or challenges parents often face.

Conversely, we also found a ready mix of EdTech for children and apps for parents, ready to sell the latest platform promising parents easy access to educational content or stress-free monitoring of their children’s activities. There must be a middle ground, we continue to believe, between fear and hype.

Our resulting report was discussed at an expert round table, and many of the experts who participated have since blogged for us on the LSE’s Media Policy Project blog. Our report (which we talk about in this video) urged policy makers to:

- transcend the view of screen time as all about risk;

- recognize and respect the diverse approaches taken by parents;

- reject the emphasis on screen time and instead focus on the content and context of viewing and playing, as well as the positive connections these can build; and

- ask how they can better support parents in guiding children not only away from risk but also toward opportunities in digital environments.

Of course experts never agree! Around Christmas 2016, 40 experts called for government action to prevent the mental health disaster waiting to happen as a result of too much screen time. In response, fully twice that many experts called on the first group to provide the evidence of harm, claiming that the very notion of screen time is meaningless.

Shortly after, a study by the University of Oxford argued for the ‘Goldilocks effect‘ according to which around four hours of screen time per day is just fine, bringing benefits to children’s learning and socializing, although much more and, interestingly, much less than four hours can be a sign of problems.

So, rather than watching the clock, we advise parents to watch their children and ask themselves, are they:

- Eating and sleeping enough?

- Physically healthy?

- Connecting socially with friends and family – through technology or otherwise?

- Engaged in school?

- Enjoying and pursuing hobbies and interests – through technology or beyond?

If the answer to these questions is more or less ‘yes’, then perhaps the problem of ‘screen time’ is less dramatic than many parents have been led to believe. The notion of ‘addiction’ to the screen requires particular care, and certainly cannot be determined by simple measures of time.

Despite all this activity on the part of experts, and continuing anxiety on the part of parents, caught in the middle of conflicting views, the UK still has no equivalent of the AAP which has, at least, now reviewed the latest evidence and reached a more balanced view, although there are still problems with their analysis.

As we concluded:

This debate will not go away as the complexities and demands of the digital age bring ever new challenges to today’s parents. But the digital media will also not go away, so finding new strategies to empower rather than chastise parents, and to harness the benefits of these media as well as managing the risks is, surely, urgently needed.

So, who will marshal the best evidence to guide parents on these often complex and fast-changing matters? The regulators are getting involved in terms of managing the media environment itself. Some parts of the industry are doing their best to ensure screen time is positively beneficial. None of this does away with the reasons that parents worry, sometimes with good cause. On the other hand, there are signs that parents are changing in their view of screen media, and gaining the skills to use them more wisely. But as they themselves say, they need more guidance to ensure children benefit. And we definitely need more research as really young children use digital screens.

Still, we have looked in vain for an authoritative body — the government? — to step up and guide parents with the clear yet nuanced advice they need.

Notes

This text was originally published on the DML Central blog and has been re-posted with permission.

This post gives the views of the authors and does not represent the position of the LSE Parenting for a Digital Future blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.