By Randolph Luca Bruno (University College London), Nauro Ferreira Campos (University College London), and Saul Estrin (London School of Economics and Political Science)

By Randolph Luca Bruno (University College London), Nauro Ferreira Campos (University College London), and Saul Estrin (London School of Economics and Political Science)

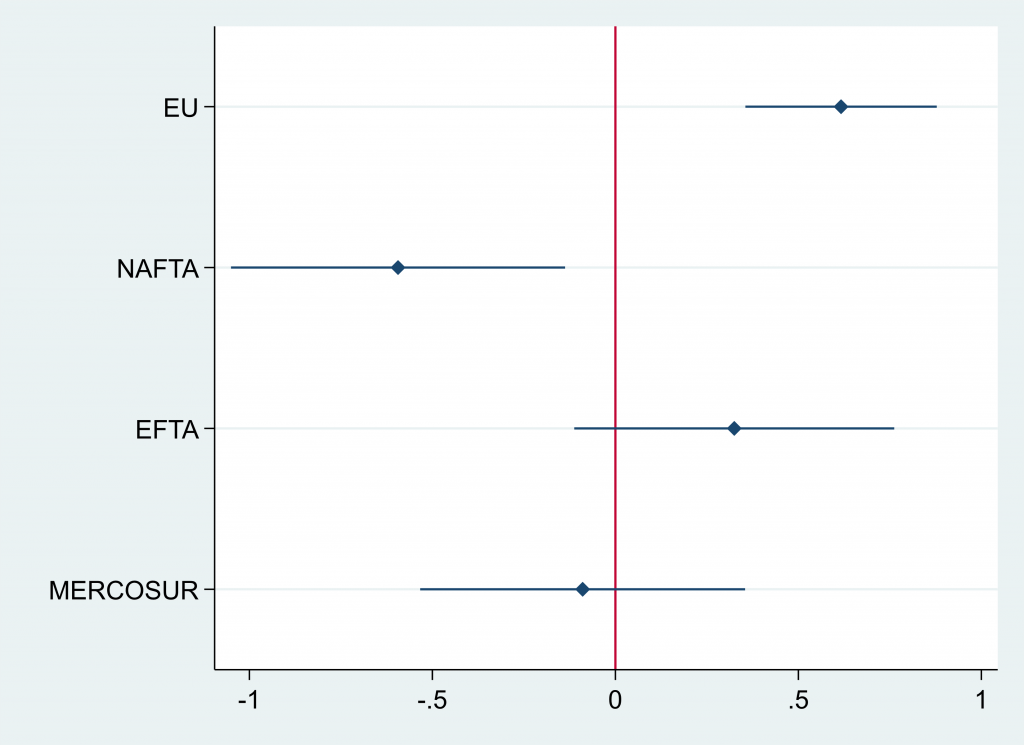

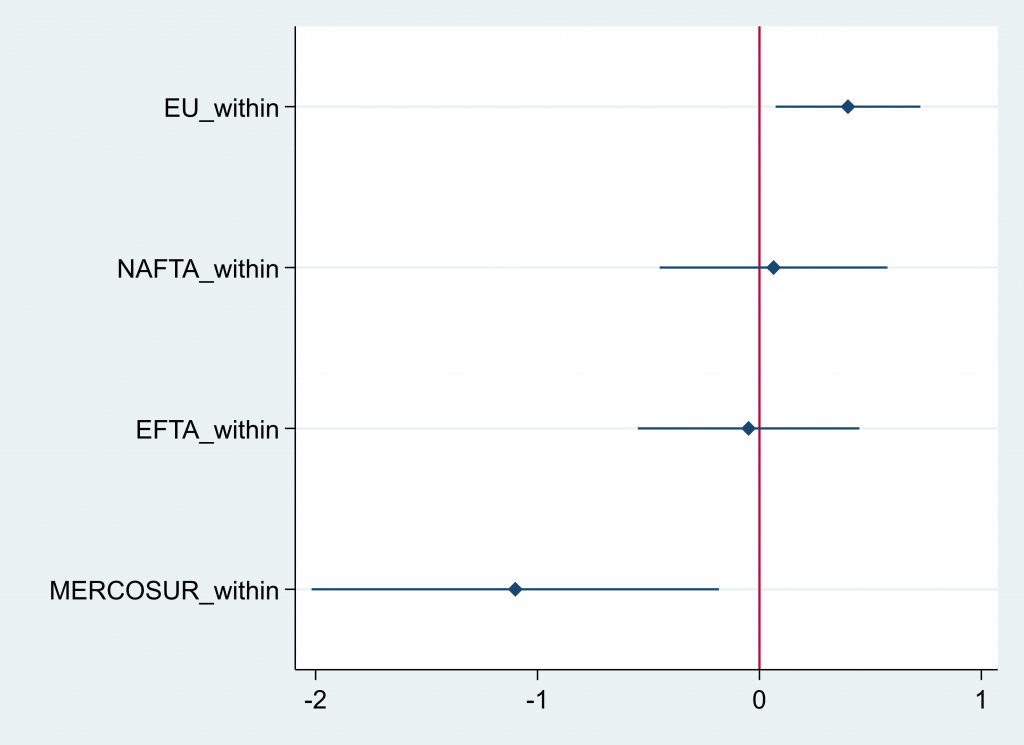

Compared to other large integrated trading areas such as NAFTA, EFTA and Mercosur, the authors find the EU to be the most attractive for FDI for both internal and external inflows, and by a significant margin.

Are the European Union and the Single Market delivering in terms of strengthening institutions, and providing opportunities to its member countries to become more attractive and resilient in the medium to long run? From the perspective of foreign direct investment (FDI), where cross-border financial flows represent a long-term commitment at the corporate level, this is certainly the case.

To consider this important topic, we have drawn on one the most comprehensive global databases on country-to-country FDI, compiled by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Our database is the first that allows for an evaluation of the impact of various institutional arrangements on FDI inflows. We estimate EU membership enhances FDI significantly: the premium is in the order of 60% for external FDI flows and 50% for internal ones. These represent sizable and policy-relevant effects.

Our methodologically robust findings are timely given the pressure currently faced by the European Union in promoting the benefits of the European Integration project. This has been brought into question by a variety of recent events including the COVID-19 pandemic; challenging diplomatic relationships with superpowers like the USA, Russia and China; general political instability across the world; and not least, Brexit.

Our research has identified a clear, large and significant link between being a member of the European project and attracting foreign direct investment. This raises the question: why should we care about FDI? The answer is that FDI is not just another form of capital flow; it brings much wider economic effects.

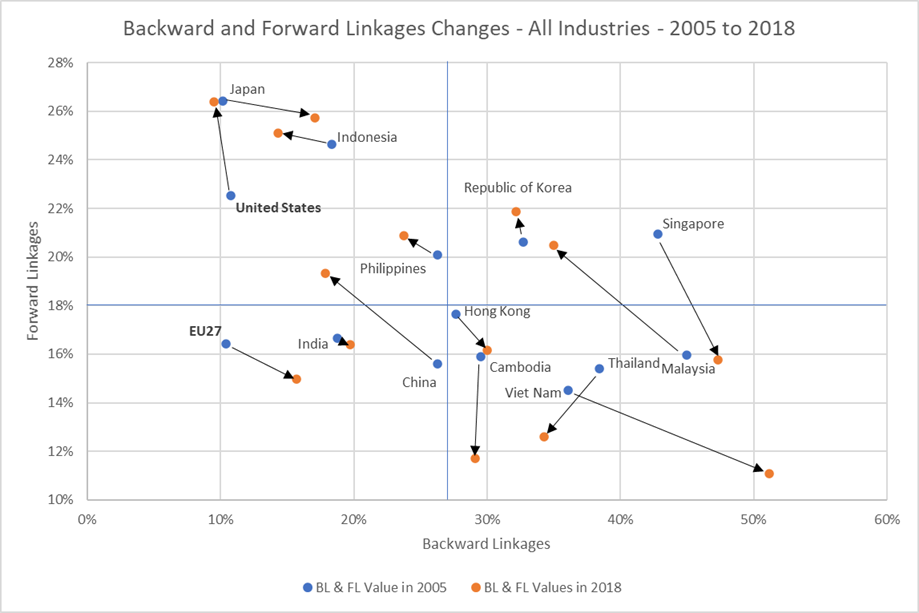

Foreign capital entering a country for the long term plays an important role in the economic development of the recipient economies. It is a form of capital accumulation that generates growth and, if sourced from technologically more advanced countries, also leads to enhanced productivity. This can occur both within the same industries of the recipient companies (for instance, domestic IT companies living side by side with foreign-owned ones as in Silicon Valley) as well as vertically up and down supply chains (domestic IT companies providing services to or receiving services from foreign-owned IT companies).

Indeed, scholars have argued that FDI can also stimulate domestic firms’ technological innovation by increasing competitive pressure on them, as well as by diffusing frontier management practices. FDI may also exhibit patterns of complementarity not only with respect to trade, but also with other elements of financial globalisation. If FDI matters, and the EU attracts more FDI, this is all good news for the European project.

It would also be appropriate to ask another important question: what about the FDI directed to other integrated economic areas, for example the North American Free Trade Area (NAFTA, composed of USA, Mexico, and Canada); the European Free Trade Area (EFTA, comprising Switzerland, Iceland, Norway, and Lichtenstein,) and the Southern Common Market (Mercosur, composed of Argentina Brazil, Uruguay, and Paraguay)? Do these also stimulate FDI or is the EU special in this respect? We have addressed this question and found the EU to be the most attractive of all the integrated blocs in terms of FDI (see the estimated benefit of each area in Figure 1 below), and by a big margin! Thus, we do not find evidence that similar levels of benefits can be obtained by joining alternative trading areas, let alone by trading under World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules.

We have found that the cornerstone of the EU’s success derives from access to the Single Market with its “four freedoms of movement” (labour, capital, services and people). The possibility to make foreign capital work within the whole EU from any “point of entry” has important research and policy implications.

In terms of future research, we think that four main issues arise from this study. Firstly, there is the issue of the sectoral composition of FDI since effects may be heterogeneous across sectors, for instance services vs. manufacturing. A second suggestion is to investigate whether there are complementary relationships between FDI and other forms of integration, such as trade or financial flows. A third would be to dwell deeper on those institutional aspects that have so far received limited attention in the literature. These might include issues such as corruption, the rule of law, inequality, and the quality of state institutions, on the one hand, and corporate tax rates and tax havens, on the other. Finally, we think the issue of expectations deserves more detailed treatment. For instance, we know EU accession measured by its date does not fully capture FDI effects that occur prior to EU membership (e.g., accession negotiations and/or changes to candidate status).

Regarding policy implications, FDI until very recently has been one of the areas upon which the EU was broadly silent. However, this has recently begun to change. Former Commission President Juncker presented a proposal to create the first EU-wide framework for FDI during his 2017 State of the Union address. The proposal was adopted by the European Parliament and the Council in March 2019 and has now entered into force, although it was restricted to screening foreign investment into the EU. However, Europe was still recovering from a global financial crisis in which an investment slowdown played a central role when the pandemic hit. Many well‐designed policy proposals were on the table but have not yet received the priority (by which we mean the financial resources and political support and focus) they require. This new framework is a step in the right direction, but it does not suffice. In principle, FDI can play a key role in accelerating and deepening the recovery because of the robustness of its long‐term productivity effects. We have shown that these can be further supported by EU integration.

This post is based on the article “The Effect on Foreign Direct Investment of Membership in the European Union”, by Randolph Luca Bruno (University College London), Nauro Ferreira Campos (University College London), and Saul Estrin (London School of Economics and Political Science) published in The Journal of Common Market Studies (2021), https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jcms.13131

Randolph Luca Bruno is Associate Professor in Economics at the UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies

Nauro Ferreira Campos is Professor in Economics at the UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies

Saul Estrin is Emeritus Professor of Management Economics and Strategy at LSE

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the GILD blog, nor the LSE.