In The Suspect: Counterterrorism, Islam and the Security State, Rizwaan Sabir draws on his own experience to tell the story of what happens when a Muslim academic researching Al-Qaeda post-9/11 is accused of terrorism himself. This candid book testifies as to how counterterrorism legislation and policy can damage and mentally harm individuals in significant and often hidden ways, all under the guise of legally sanctioned police and security state activity, writes Shereen Fernandez.

The Suspect: Counterterrorism, Islam and the Security State. Rizwaan Sabir. Pluto Press. 2022.

Find this book (affiliate link):![]()

Rizwaan Sabir’s The Suspect: Counterterrorism, Islam and the Security State tells a story of what happens when a Muslim academic researching Al-Qaeda post-9/11 finds himself being accused of terrorism himself. The terrorism charge that Sabir faced, along with his co-accused Hicham Yezza, who worked in the same institution and was serving as Sabir’s academic mentor, was Section 58 of the UK Terrorism Act 2000. This law criminalises the possession of information deemed ‘useful to somebody who is preparing or committing terrorism’, irrespective of the reason for one’s possession. It’s the nature of the information that is a crime, not the intention one holds it for (53).

Rizwaan Sabir’s The Suspect: Counterterrorism, Islam and the Security State tells a story of what happens when a Muslim academic researching Al-Qaeda post-9/11 finds himself being accused of terrorism himself. The terrorism charge that Sabir faced, along with his co-accused Hicham Yezza, who worked in the same institution and was serving as Sabir’s academic mentor, was Section 58 of the UK Terrorism Act 2000. This law criminalises the possession of information deemed ‘useful to somebody who is preparing or committing terrorism’, irrespective of the reason for one’s possession. It’s the nature of the information that is a crime, not the intention one holds it for (53).

Sabir was researching Al-Qaeda in Iraq for his Master’s dissertation and an upcoming PhD when he came across a declassified document available for download on the US Department of Justice website called the ‘Al-Qaeda Training Manual’. To put the charge into context, Sabir tells us: ‘Not only was the document that Hicham and I were arrested, detained and investigated for a document that had been given the title of ‘‘Al-Qaeda Training Manual’’ by the US government, but it was also an incomplete and truncated version compared to the fuller, longer versions that were, at the time, publicly available via the university’s library and can be downloaded or purchased until this day from high-street bookshops and US military websites’ (25).

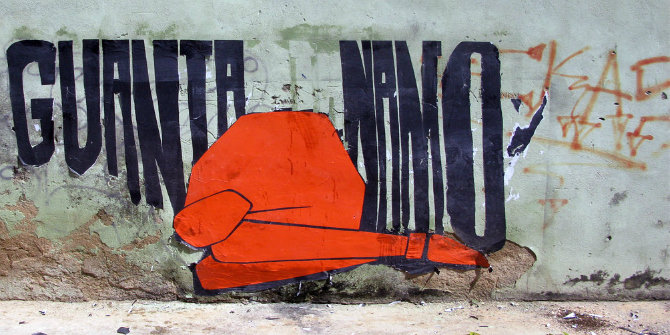

The UK began to ever-expand its counterterrorism infrastructure as the ‘War on Terror’ was getting into swing in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, in the name of ‘securing’ the nation from the ever-increasing threat of terrorism. Over the years, accompanying the laws, increased surveillance powers and increased militarisation of policing has been the Prevent strategy. This legally compels public sector workers in schools, universities and healthcare settings to report individuals as part of the ‘Prevent Duty’ if they are deemed to be ‘extremists’ or ‘radicals’, in a pre-emptive move to curb future terrorism.

Image Credit: Modified version of Photo by Rene Böhmer on Unsplash

The Suspect opens by recalling Sabir’s reactions to 9/11, a sort of ‘awakening’ as the chapter is titled, where ‘nationalist’ identifiers collapsed into ‘the Muslim’. As he grappled with coverage of the wars launched to avenge and prevent another 9/11, Sabir was offered a space at university to explore his curiosities and ended up enrolling in a Politics degree where he ‘listened attentively to every word that was uttered’ by his professors (3).

To think that these spaces of education are now subject to intense regulation and monitoring by Prevent is a depressing reality that Sabir persuasively documents throughout the book, especially when he speaks about mental health services, whose help he desperately needs, but is unable to engage with because of the way this area has been co-opted into the state’s surveillance apparatus (see Chapters 20 and 28). The Suspect also reveals how untrusting these spaces of education and health are of racialised Muslim minorities, given that the University of Nottingham did not come to Sabir’s defence except for a handful of academics (see Chapter 8).

The impacts of counterterrorism legislation on Muslim communities in the UK and elsewhere is well documented, with many human rights organisations coming out against the violence of these measures, which curtail civil liberties and create a repressive environment for racialised Muslim communities. Sabir speaks candidly about the disastrous and traumatising consequences that his experiences of arrest, detention and surveillance have had on his mental health. He could not trust anyone, even his family, and speaks about living rough in his car so that he was ‘constantly on the move’ and could know if he was being followed (102). In another instance, he relates in harrowing detail how he drove 1200 miles in 24 hours across Europe to avoid spending time with a family member he suspected of working for the intelligence services during the course of going through a mental health breakdown (166). In the depths of his mental health crisis, Sabir describes how the sleeping pills he was prescribed by a psychiatric nurse seemed to be a symbolic representation of the state’s attempt to depoliticise him or to make him ‘sleep’, as he puts it (112). It all felt like an elaborate programme of surveillance and coercive control in Sabir’s traumatised mind.

In many ways, The Suspect confirms two suspicions I feared as a Muslim conducting research on the ‘War on Terror’ myself. Firstly, Muslim academics researching terrorism who possess the ‘wrong’ documents or materials will be at risk of coercive intervention at the hands of the state, illustrating how studying and researching political violence and terrorism is not a level playing field. Secondly, the fear this unequal playing field creates amongst young Muslim students, researchers and scholars can have disastrous consequences for Muslim participation in the production of knowledge on a subject area where their voices are already underrepresented and their motives questioned. The experience of Dr Tarek Younis, for instance, is the latest example of where our motives, analysis and allegiances are questioned and scrutinised, even when this is our area of research specialism.

For countless Muslims, The Suspect shows how alongside legal arrest powers, the creation of Prevent and the assumptions of guilt shadow us wherever we go and create a disciplinary and coercive environment in which fear and (self)censorship run rampant. ‘Despite not being subjected to violence themselves, people, and especially racialised Muslims, have been coercively influenced and have changed their behaviour on the basis of an overarching threat of violence looming over them,’ Sabir writes. ‘On more than one occasion, people told me that based on their knowledge of my arrest and detention, [they have taken steps] to minimise the risk of falling foul of anti-terror laws’ (140).

Sabir won an out-of-court settlement and was awarded £20,000 in damages (Chapter 10). He felt a sense of empowerment at the time but the stigmatisation of a terrorism arrest, even if it was a wrongful one, did not stop him from encountering the authorities and their surveillance machine. Sabir documents how he was labelled as a ‘Subject of Interest’ and routinely pulled over by police. On one occasion, he was sitting in a car with a friend outside of his family home when police pulled him over under Section 43 of the Terrorism Act: a stop and search that was eventually declared ‘unlawful’ (61).

Sabir also dedicates short chapters to describe multiple stops, including at the border, where he was subject to intelligence-driven detentions under Schedule 7 of the Terrorism Act 2000 and during his travel to the US, Europe and the Middle East. These insinuations of supporting terrorism or being a potential terrorist follow individuals to the detriment of a person’s family, friends and their psychiatric and physical health on a constant and routine basis. Trauma, as the saying goes, travels. Or, as Sabir writes, ‘Once you are marked as a ‘‘subject of interest’’ it becomes difficult to become uninteresting’ (59).

As I read the book, I wondered what accountability would look like for those caught in the ever-expanding webs of the ‘War on Terror’, from Prevent to Schedule 7. Sabir speaks candidly and openly about the pain of writing The Suspect and the trauma it triggered whilst doing so. Accountability, it seems, comes at a cost, this book troublingly reminds us.

Ironic as it may be, The Suspect should be read as a manual of sorts for practitioners and institutions who continue to uphold counterterrorism legislation and policies such as Prevent. The book testifies as to how counterterrorism legislation and policy, even those repackaged as ‘safeguarding’, can psychiatrically damage and mentally harm individuals in significant and often hidden ways, and all under the guise of legally sanctioned police and security state activity.

Sabir’s case and what it represents is both exceptional and unexceptional; exceptional in the sense that this arrest could happen to any Muslim researcher who studies terrorism and political violence at university. Unexceptional in the sense that since 9/11, 2418 people have been arrested for suspected terrorism and released without charge. They will have experienced similar feelings and emotions to what Sabir now lives with, something which he is keen to highlight: ‘my experiences and what I have described […] reflect a broader set of struggles, suspicions, and harms that affect thousands of other Muslims and people of colour too. What happened to me is not an exception to the rule. It is the rule’ (59).

The rampant Islamophobia and racism that counterterrorism policies breed and are based upon should be a warning to institutions: you cannot commit to building an inclusive space if the message being broadcast is that Muslims are not to be trusted. As I reached the conclusions of The Suspect, it was painfully obvious that as these laws and policies sweep into our everyday spaces to disrupt the trust we once had and attempt to depoliticise us, nobody wins except those trying to maintain and normalise an authoritarian system of power that seeks to control racialised ‘others’. But, I took heart in the final few chapters where Sabir explains how we, as ‘communities of struggle’, can work together in solidarity to resist, challenge and overcome the encroachments made into our daily lives in the name of countering terrorism.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.