Credit for all images: Michael Dezuanni & Anna Whateley

Credit for all images: Michael Dezuanni & Anna Whateley

Michael Dezuanni and Anna Whateley tell us about their own home, technology in family life and the role of Minecraft in teaching digital skills across generations. They both work at Queensland University of Technology, Michael is Deputy Director of the Children and Youth Research Centre, Anna teaches adolescent fiction and the sociology of education.

Michael Dezuanni and Anna Whateley tell us about their own home, technology in family life and the role of Minecraft in teaching digital skills across generations. They both work at Queensland University of Technology, Michael is Deputy Director of the Children and Youth Research Centre, Anna teaches adolescent fiction and the sociology of education.

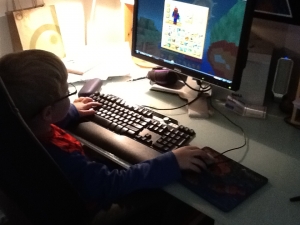

Minecraft is one of the most popular digital games played by children today. It is a deceptively simple game in which players gather materials in the form of blocks to craft items for designing and building. They can choose to fight zombies, ‘creepers’ and other creatures to gain points and acquire more materials. As players gain expertise and refine their craft skills, their builds become more elaborate and complex.

Parents seem to react to their children’s Minecraft play with a combination of marvel at their children’s amazing creations and trepidation about the extent of their children’s knowledge about a world they themselves know little about. As online education expert Mimi Ito argues, Minecraft is the kind of game that rewrites the playbook for learning and Cathy Lewin from the Centre for Research in Technology, Innovation and Play for Learning suggests that Minecraft has a range of benefits for children.

Our family came to Minecraft late in 2011 when introduced to it by Anna’s brother, and we soon found ourselves spending a lot of time playing the game as an extended family, cousins and grandparents included – we became ‘Minecraft parents’. Anna worked out how to set up a server, and soon our children’s friends began to come onto the server to hang out in our Minecraft ‘digital backyard’, which we called Babylon. It was a safe space for children aged 4-10 to play, build and explore.

The research on Babylon

As researchers and educators in the fields of digital literacy, children’s and youth culture and sociology, we became fascinated by what was clearly an entirely new way to be together as a family and the implications of hanging out in digital space for parenting, sibling relations, friendships and play dates. Before long, we found ourselves seeking a university ethics clearance to gather data about our ‘experiment’.

As researchers and educators in the fields of digital literacy, children’s and youth culture and sociology, we became fascinated by what was clearly an entirely new way to be together as a family and the implications of hanging out in digital space for parenting, sibling relations, friendships and play dates. Before long, we found ourselves seeking a university ethics clearance to gather data about our ‘experiment’.

Other parents and the children themselves agreed to let us collect data about their experiences in and around Babylon. Our research is a form of digital ethnography in which we generate data through observing and critically reflecting about our play sessions, which provides us with extremely rich, descriptive data about Minecraft play in the family home. We are very aware, of course, of the inherent difficulty of treating our data objectively, but our aim is not to find the ‘truth’ of family Minecraft play. Rather, we aim to represent our own narrative to explore the complexities of digital parenting in everyday life.

Joining in

Minecraft parenting is rewarding but challenging – the distance between what children and parents know is potentially immense. Initially, we had to muster up the courage to play Minecraft – it is awkward and confronting to be a complete beginner, particularly when half the ‘fun’ of playing Minecraft is to display your expertise. Other parents were reluctant to ‘have a go’ and to see the game as a space for potentially meaningful interaction with their children. Outside our extended family only one other parent actually played on the server, although most of the parents wanted to know about the game and participated in discussions. This is not a criticism, but rather an acknowledgement that not all parents readily join their children in digital game play, although they frequently take part in other forms of play.

Minecraft parenting is rewarding but challenging – the distance between what children and parents know is potentially immense. Initially, we had to muster up the courage to play Minecraft – it is awkward and confronting to be a complete beginner, particularly when half the ‘fun’ of playing Minecraft is to display your expertise. Other parents were reluctant to ‘have a go’ and to see the game as a space for potentially meaningful interaction with their children. Outside our extended family only one other parent actually played on the server, although most of the parents wanted to know about the game and participated in discussions. This is not a criticism, but rather an acknowledgement that not all parents readily join their children in digital game play, although they frequently take part in other forms of play.

Managing Babylon has not been simple. Running a Minecraft server requires substantial levels of technical know-how, and while Anna enjoyed the challenge, we recognise that not many parents can spend time learning the complex processes for establishing and modifying a server.

Minecraft ‘literacy’ is required to know how best to ‘control’ the world as an appropriate, rewarding and fun space for children. Anna learned the language and practices of using a variety of game ‘plugins’ to facilitate in-world control, which included safety features so that children would not lose their items if they died in-game, game time could be manipulated (to avoid monsters coming out at night), and teleportation was enabled to allow a safe and easy way ‘home’.

Playing together

From the outset we believed a key benefit of running a server for our children and their friends was that they could learn to play well together in an online environment. We wanted them to develop a sense of online ethics with basic rules such as no griefing (breaking other players’ creations), and all players agreed to a code of conduct. Clear expectations for play were established, just as they would be in most environments involving 4- to 10-year-old children.

From the outset we believed a key benefit of running a server for our children and their friends was that they could learn to play well together in an online environment. We wanted them to develop a sense of online ethics with basic rules such as no griefing (breaking other players’ creations), and all players agreed to a code of conduct. Clear expectations for play were established, just as they would be in most environments involving 4- to 10-year-old children.

The benefits

Minecraft has enriched our interactions with our children, their friends and their parents. School pick-up times have often been infused with rich discussions; other parents talk with Anna about the game and its requirements (both technical and social). The children often run up to talk excitedly about the game. It provides a way for children and parents to share conversations about the game play, and the children often want to display their expertise and ask questions about intricate aspects of the game.

For us, Minecraft is an exemplary instance of digital culture that can provide us with insights into the future of childhood, parenting and learning.

An important challenge moving forward is how parents can more easily take part in their children’s digital lives because there are quite clear benefits for both children and parents when this occurs. We hope our children will build on the digital literacies they have begun to acquire in and around Minecraft as they get older and their digital participation becomes more independent.

The story emerging from our Minecraft research is that proactive engagement with digital media enables us to support our children’s digital participation in appropriate ways. The question is whether we will continue to have the courage to challenge our digital selves, and, of course, the extent to which our children, as they get older, will be happy for us to ‘hang out’ with them in their digital spaces and places.