Credit: M. Newman, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Credit: M. Newman, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Technology use is changing fast, which makes things difficult for parents trying to prepare their children for the future. Sonia Livingstone looks at the recent CHILDWISE report¹ and provides four key messages to help predict what’s coming. Sonia is Professor of Social Psychology at LSE’s Department of Media and Communications and has more than 25 years of experience in media research with a particular focus on children and young people. She is the lead investigator of the Parenting for a Digital Future research project.

Technology use is changing fast, which makes things difficult for parents trying to prepare their children for the future. Sonia Livingstone looks at the recent CHILDWISE report¹ and provides four key messages to help predict what’s coming. Sonia is Professor of Social Psychology at LSE’s Department of Media and Communications and has more than 25 years of experience in media research with a particular focus on children and young people. She is the lead investigator of the Parenting for a Digital Future research project.

Everyone would love to know what the future holds, but perhaps parents more than most, because they must bring up their children in the here-and-now in a way that will equip them for a world still some decades away.

Our project focuses specifically on ‘parenting for a digital future’, seeking to understand how parents approach such a seemingly-impossible task – with what hopes and anxieties or worries about their child, and with what vision of ‘the digital’ or sense of their own agency?

Many have commented on today’s sense of time speeded up – more technologies, more information, more change on the way. No wonder parents can feel overwhelmed, even as they welcome ever smarter, more personalised, converged and flexible technologies into their homes.

What technology means

Here’s where evidence can be useful, even surprising on occasion. In a recent post, I reviewed trends in family technology uses over the past two decades, as tracked by the specialist market research agency, CHILDWISE. In a subsequent report, this data is used to predict what’s coming in the next few years. Here’s my four key messages, and some new and pressing questions:

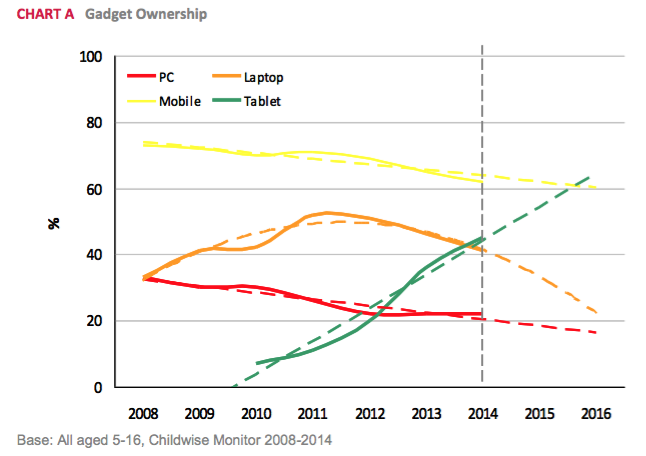

1. New technology doesn’t always mean more technology. While the tablet is proving a hugely popular device, mobile phone ownership among children, along with TV sets in their bedrooms, is tailing off. What does this mean? Some parents are establishing a ‘no screen in the bedroom’ rule, replacing older rules about whether to allow TV in the bedroom. We might also ask critical questions about the affordances of these different devices – it’s quick to download or stream content onto a tablet, but is it as easy to create, design, code or upload content onto a tablet compared with a laptop? Is anything “lost” if children favour tablets over laptops?

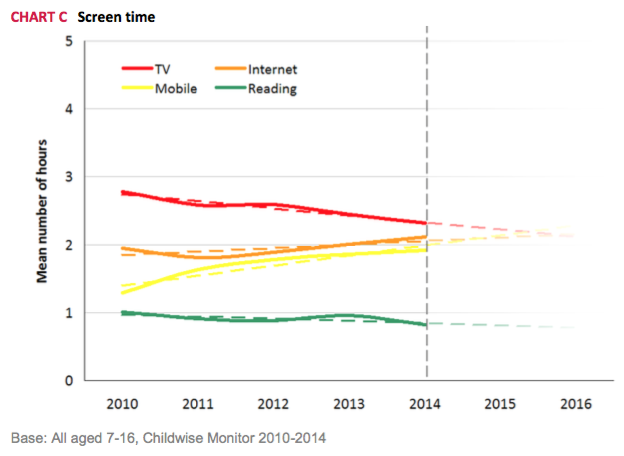

2. More technology doesn’t always mean more time on technology. Overall screen time is levelling out – with more time online/on mobile devices, but less time watching TV or reading. On the one hand, a human limit is being reached – children have engaged with one screen or another for around two hours per day for decades past, and this is not set to change. However, engaging with multiple screens at once, and watching short videos rather than concentrating on long films or texts, marks a potentially fundamental shift in literacy practice, partly in response to commensurate increased efforts on the part of the content industry to grab and hold children’s attention.

3. More technology means less sharing. The more devices and services family members can access, and the more these become tailored and targeted to specific groups (mums or dads, toddlers or teens, girls or boys), the less there may be that families share. Let’s not get overly nostalgic about shared media experiences that never really happened very often in practice. But still, it’s noteworthy that as everyone engages with their own screen – and with mainstream channels broadcasting ever less for children – it’s not only harder for parents to look over their children’s shoulder or to casually discuss what they’re watching but, more important, harder to find content enjoyed across gender and generational divisions. This means:

- a decline in terrestrial viewing among children as children switch to dedicated children’s channels (notably CBBC) and/or YouTube;

- children divide their attention across many more channels than before – 19 channels watched by 20% and more of children in 2014, compared to four channels in 1995.

4. More technology will also mean different technology. CHILDWISE lists an array of smart technologies, many of them still regarded as ‘in the future’ by parents, even though they are now entering the child market. These include smart watches, activity trackers, virtual reality headsets, wearables and, as discussed previously, ‘Smart Barbie‘. At this stage, the hype tends to outweigh any practical assessment of either benefits or risks. What we might guess from the appropriation of previously new technologies, however, is that these will indeed become commonplace before we have developed a robust policy to manage the risks or, perhaps more surprisingly, formulated a clear vision of the benefits either.

NOTES

¹ While unfortunately this report isn’t cheap, I am glad to have permission to reproduce some key findings and charts.