Teens’ media practices are influenced by their parents’ attitudes to gender equality, according to recent research in the US by Plan International. The study also found that teens – particularly those from ethnic minorities – would like more education on issues such as consent, equality and safety online. This post considers how both parents and educators might address such concerns. Kate Gilchrist is a PhD researcher at LSE’s Department of Media and Communications whose research focuses on media representations of gender.

Teens’ media practices are influenced by their parents’ attitudes to gender equality, according to recent research in the US by Plan International. The study also found that teens – particularly those from ethnic minorities – would like more education on issues such as consent, equality and safety online. This post considers how both parents and educators might address such concerns. Kate Gilchrist is a PhD researcher at LSE’s Department of Media and Communications whose research focuses on media representations of gender.

Teenagers are influenced by parental attitudes when it comes to gender equality according to new research by Plan International. A national survey of US adolescents aged 10-19 found a relationship between parental attitudes and teenagers’ attitudes towards and engagement in sexualized media practices such as sexting and viewing pornography. Those who had been spoken to by a parent or teacher about the issues raised by the #metoo movement, or who had played with gender-neutral toys while growing up, were also more likely to report more favourable attitudes towards gender equality and experience less gendered discrimination online such as pressure to receive ‘likes’ on social media. The study revealed a demand from teens for better education around gender equality. The majority of those surveyed – particularly those from ethnic minorities – said that they would like to learn more from adults about issues such as sexual consent, the right to be treated equally and how to speak up if they have experienced harm.

The study

The survey was commissioned by Plan International in order to better understand how children are viewing and experiencing gendered inequality both online and offline. A representative sample of 1,006 10- to 19-year-olds were interviewed from households across the US in April to June 2018. The data were analysed to examine where statistical correlations occurred between attitudes towards gender equality and other attitudes and behaviours, to help explore why and how such attitudes were formed.

Parental attitudes, ‘sexting’ and pornography

Consistent with existing studies, ‘sexting’ was found to be a common gendered phenomenon among US teens:

- One in three girls aged 14 to 19 reported that “all or most” of their friends had been asked by a boy to send sexy or naked pictures of themselves.

- Boys said that 25% of them had or knew a peer who had requested such pictures from girls.

But boys whose fathers or other male family members made sexual comments or sexist jokes about women were much more likely to report that they thought it was ok to ask girls to send them sexy or naked pictures. Such a finding is important when the survey also showed that:

- As many as 29% of boys aged 14 to 19 said they had heard their dads make such comments.

- Almost half (47%) said other men in their family had done so.

There was also a correlation between boys thinking it is ok to ask girls to send them such images and them being more likely to have viewed pornography, as well as their peers making sexist jokes. There was a significant link or correlation between fathers making sexist jokes or comments and boys being more likely to report viewing pornography, reinforcing this cycle. While there is no evidence to suggest a direct connection between these factors[1], such findings suggest that if parents are concerned about their teen viewing pornography or engaging in ‘sexting’ they should consider the influence that their own comments or attitudes may be having on their teen’s practices.

Parents should also consider the kinds of toys that their children are playing with. Boys who played with mostly gender-neutral toys when growing up were more likely to judge girls on their personality rather than their appearance. Equally, there was also a link between girls playing with gender-neutral toys and girls’ experiences of gendered media practices. They were less likely to feel pressure to be liked on social media (such pressure is higher for girls) or to know friends who had been asked to engage in sexting, if they had grown up mostly playing with gender-neutral toys.

A desire to learn more

Teenagers reported that they want to be taught more by adults about gender inequality. A majority of teens said that they wanted to learn more on topics such as:

- the right to be treated equally (57%)

- the right to always be safe (57%)

- how to speak out if they had been hurt (56%).

Over a third (36%) of girls said they had already been spoken to by a parent, or 23% by a teacher, about sexual harassment as a result of the #metoo movement, 28% of boys said they had been spoken to by a parent and 21% by a teacher. Those who had been spoken to were found to have more positive attitudes to gender equality.

Girls were often more likely than boys to state that they wanted to learn more about certain topics:

- 60% of 14- to 19-year-old girls wanted to know more about consent, compared to 46% of boys.

- 62% of 14- to 19-year-old girls wanted to learn more about being valued for more than their appearance, compared to 42% of boys.

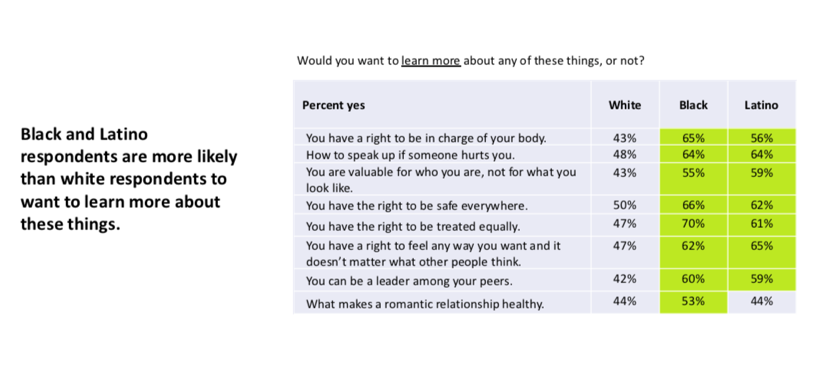

Black and Latino respondents were also consistently more likely to report that they wanted to learn more about such topics (see graph below):

- 64% of black and Latino teens wanted to know about how to speak up if someone hurts them, compared to only 48% of white teens.

It is unfortunate that due to sample restrictions the possible interaction between gender and ethnicity was not explored in the analysis to examine how gender and race interact to intensify pressures on certain groups.

Further research could therefore examine how the categories of both gender and race intersect here to see how multiple factors may create a ‘double bind’ (a bind defined as “a rhetorical construct that posits two and only two alternatives, one or both penalising the person being offered them”[2]) on groups who occupy ‘deprivileged’ positions of both race and gender (where they don’t receive the ‘privilege’ of ‘unearned benefits which are accrued’ to those who occupy a higher status within the social hierarchy). Yet these findings do show that better sex and relationships education is needed, especially around consent and safety. Teachers and parents particularly need to focus on teaching teens how they can:

- better approach or speak up about the pressures or risk of harm they experience online

- limit the damage that they may be causing to others via what are highly gendered media practices.

And while parents often find it hard to talk to their teenagers about such topics, teachers may be best placed to meet this need. Such education also needs to take into account the varying experiences and needs of girls and boys and different racial groups. Finally parents should be mindful of what kinds of toys their children play with and the impact that their attitudes towards gender equality may have.

Notes

[1] As the report states: while there is not a direct link between the factors discussed, the data showed a significant relationship between such factors of media use and parental attitudes which shaped teenager’s experiences of and attitudes to gender inequality.

[2] Crosby, E. D. (2016). Chased by the Double Bind: Intersectionality and the Disciplining of Lolo Jones. Women’s Studies in Communication, 39(2), 228-248.

This post gives the views of the authors and does not represent the position of the LSE Parenting for a Digital Future blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.