“Digital technology connects … physical and virtual spaces, creating both local and global digital playgrounds. Some of these spaces are designed with play in mind, and others are not.” (Colvert, 2021, p. 18)

“Digital technology connects … physical and virtual spaces, creating both local and global digital playgrounds. Some of these spaces are designed with play in mind, and others are not.” (Colvert, 2021, p. 18)

How do the design features of the digital environment enable or undermine the qualities of play that children experience in relation to specific digital products and services? In our national survey of UK children, we asked them each to judge two of these in terms of the qualities of play and their digital features. We can now show how Playful by Design works in practice by identifying the digital features that enable or undermine the qualities of play for each app in turn.

Fortnite is a free online action-packed video game, most popular among children aged 10 – 12 and known for its variety of game modes (e.g., Battle Royale, Creative, Save the World) and in-game items (e.g., weapons, vehicles, submodes, etc.). Offered by Epic Games, Fortnite operates on multiple operating systems and platforms, including Windows, iOS, PlayStation 4, Xbox and Nintendo Switch. The game generates income through in-game purchases to enhance players’ experience and unlock access to reward items and other aspects of the game.

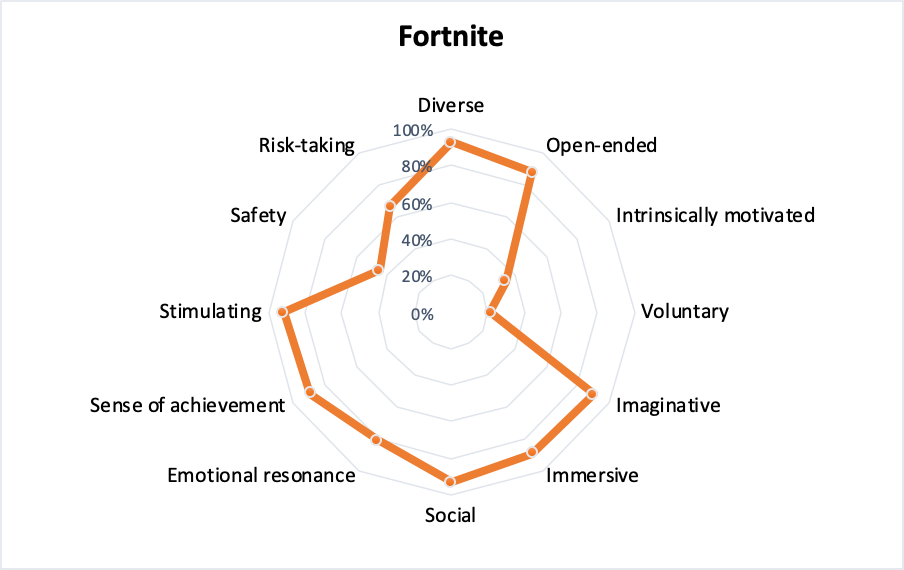

Figure 5: Children’s views of the qualities of free play in Fortnite (% agree) (Fortnite base: 241, 6–17-year-olds)

Children who responded to our survey portrayed the qualities of their play on Fortnite as predominantly social (93% agree) and stimulating (92%), but that the game offered somewhat limited voluntary (21%) play and safety (46%). That said, a significant proportion (37%) of younger girls (6 – 12 years old) found play on Fortnite voluntary while girls aged 13 – 17 (14%), boys aged 6 – 12 (21%) and boys aged 13 – 17 (13%) found the game less voluntary.

According to our survey, children aged 10-17 who play Fortnite saw its design features as ‘good for children their age’, intergenerational, creative and communicative. Corresponding with the survey, children and young people in our consultation valued the communication tools in and around Fortnite, the team-based game mechanic and variety of in-game virtual items, which they said afforded them the social, stimulating, immersive, diverse and some imaginative qualities of play.

“I play with my cousin. So, we video call and then we just play together on that… we video call we talk on the phone, not on Fortnite.” (girl, 12 years old)

A 14-year-old boy told us that he enjoyed Fortnite because it allowed him to play with his friends and “compete” against another group which makes the game stimulating, keeping him engaged.

“There’re loads of different packets that you can buy for a different amount of money. And Fortnite money is V-Bucks. And you can buy the Battle Pass with V-Bucks.” (girl, 15 years old)

However, both children and professionals working with them noted that these free play enabling features could inadvertently undermine not only children’s voluntary and intrinsic motivation to play but also safety – exposing them to contact risk and cultivating compulsion.

“If you’re in a Fortnite chat, and your party’s not on private, if someone knows your name and searches it up… And when you’re in-game chat, if you’ve got a mic on, anyone can speak. So, I’ll be in a party, and then someone’ll join if I’ve not put it on private. And there’ll just be this random person going, hello… I think it should be a bit more private.” (girl, 13 years old)

“So, when Fortnite went to… the zero event or something, where Fortnite switched off for two weeks. I know my neighbours, the 10 and the 12-year-old, they lost their minds. They’d become almost physically addicted to this game… It’s like they had a withdrawal.” (A theatre-maker working with vulnerable children)

“Fortnite is not for a child to play. So, I think what needs to be done is to develop a framework perhaps that can create a better experience for parents and kids to engage online. And I feel like that’s what’s missing.” (Father of a 10-year-old boy)

Our analysis of the features that can transform children’s play experience, based on the correlation matrix, indicates that:

- Making Fortnite less expensive and less exclusive could afford children greater safety in their play.

- Toning down the hi-tech demands and increasing age-appropriate features could afford children greater voluntary experience in their play with Fortnite.

- Curbing compulsive features, such as crossover events, could improve safety, but too many cutbacks on compulsive features could inadvertently undermine open-ended and immersive experiences.

- Making age-appropriate features more available can leverage even greater social play.

Experts recognised Fortnite’s social and team-based play appeal that children value. However, they raised concerns over the very key to Fortnite’s success – the cosmetic items which are tied to limited time events or popular licensing tie-ins and meme-worthy dance moves that are made available as in-game purchases. These in-game purchases are also known as “loot boxes”. The experts warned that such in-game spending could get out of hand without appropriate and adequate control. This warning appears to coincide with our finding that correlates expensive features – in this case, “loot boxes” – with children feeling “unsafe”.

Experts also noted that combined with high profile streamers showcasing new aspects of the game, these cosmetic items that are tied into special timed events create a “must-have” culture that propagates microtransactions and normalises perpetual spending. In addition, the experts noted that the crossover events in Fortnite cultivate compulsive attitudes among players. These design techniques encourage players to keep returning to the game and become recurrent spenders; these are being standardised through industry events (e.g., the Game Developer Conference). One expert suggested that clearer lines are needed between games whose customer base comprise mainly young players and games for adult players with compulsive practices not used in games that children play in significant numbers. Another agreed, adding that such boundaries are also relevant to the Age-Appropriate Design Code.

You can read a short version of our other case studies about Roblox and Zoom here. Our Playful by Design report contains more in-depth case studies on Fortnite, Minecraft, Nintendo Wii, Roblox, TikTok, WhatsApp, YouTube and Zoom are in our Playful by Design report.

And for our overall Playful by Design recommendations, please see Why does free play matter in a digital world?

Notes

This text was originally published on the Digital Futures Commission‘s blog and has been re-posted with permission.

This post represents the views of the authors and not the position of the Parenting for a Digital Future blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Featured image: Photo by Ron Lach on Pexels