When considering online risks and harms, it is important to account for the experiences and requirements of excluded populations of kids, rather than make assumptions around lack of access that could exclude them from targeted policies and systemic interventions to keep children safe online. Monica Bulger and Patrick Burton talk about their research at an assistance centre in Bangkok, online child sexual exploitation and what can be done to protect vulnerable children online. This is the final in a series of field dispatch reports conducted by in East Asia for UNICEF’s East Asia and Pacific Regional Office in spring of 2019. [1]

When considering online risks and harms, it is important to account for the experiences and requirements of excluded populations of kids, rather than make assumptions around lack of access that could exclude them from targeted policies and systemic interventions to keep children safe online. Monica Bulger and Patrick Burton talk about their research at an assistance centre in Bangkok, online child sexual exploitation and what can be done to protect vulnerable children online. This is the final in a series of field dispatch reports conducted by in East Asia for UNICEF’s East Asia and Pacific Regional Office in spring of 2019. [1]

Warning: this blog describes first-person accounts of sexual exploitation.

The assistance centre in Bangkok is cool in the middle of a sweltering day. Downstairs, the ceilings are high, the cool floor tiles sparkle white in the dim room. Teens are sleeping on mats on the edges of the room, many of the boys in a pile in the darker corners. We quietly go upstairs to prepare an interview space. As we’re arranging chairs, a pile of blankets between two couches starts to move and a teen boy pops his head out, smiling blearily. A social worker chastises him for being upstairs, and he shakes his head sleepily and moves to curl up on one of the couches. In this upstairs space, there is a drum set in a corner, a large conference table in the middle of the room and doorways opening to smaller rooms with comfortable chairs for counselling sessions. After a few minutes, the teens file in slowly, languidly, rubbing their eyes, but smiling at us. They tease each other and nudge shoulders as they find spaces on the upstairs couches. We divide the group, those who identify as male stay in the large conference room, those who identify as female claim couches in one of the counselling rooms.

The girls range in age from 14 to 26. We begin by discussing app use, and their descriptions are consistent with the other teens we have interviewed in Malaysia, Cambodia, and Indonesia. A 14-year-old speaks of a dating simulation app for “romantic stories…flirting,” she adds shyly, a small smile as she describes, “a boy likes a girl and they flirt.” The other teens giggle. When we talk about things that bother them on the internet, the same girl describes animal torture, shivering as she describes happening upon a video of an abused dog. The other girls nod grimly.

The girls range in age from 14 to 26. We begin by discussing app use, and their descriptions are consistent with the other teens we have interviewed in Malaysia, Cambodia, and Indonesia. A 14-year-old speaks of a dating simulation app for “romantic stories…flirting,” she adds shyly, a small smile as she describes, “a boy likes a girl and they flirt.” The other teens giggle. When we talk about things that bother them on the internet, the same girl describes animal torture, shivering as she describes happening upon a video of an abused dog. The other girls nod grimly.

Absent are the examples their social worker shared with us in interviews a day earlier. The centre provides assistance for children in need, many of whom live on the street, many of whom are sexually exploited, commercially or otherwise. The centre provides space for the teens to sleep during the day, classes and job training, counselling, and a consistent safe space as they transition toward safer work options. The location of the centre was strategic, chosen when social workers saw kids regularly sleeping during the day in public spaces in this area.

The social workers are all young women. They tell us that all of the children have dropped out of school, and most have experienced abuse at home. These teens experience various forms of abuse and risks that often translate into measurable harms, across several social media applications. For the children in prostitution, social workers describe clients sending videos to the teens’ phones to “train” them in what they like. Social workers also report that the teens themselves research pornography online to please customers and make more money. One strategy is to create a Facebook group with a name that is a code for clients. They use livestream video on Facebook for the sexual act, so members of the group can look, but can’t save it. Any time the social workers report to Facebook, the account might be shut down, but there is no law enforcement follow up. Similarly, teens have used Line (a popular South Korean social media app with over 700 million users owned by Naver, based in Japan) to live stream.

Despite many attempts, no one from Line has responded to reports. One social worker says “Any secret you want to share with your friends or family, you better use Line”. In their experience, Line will not work with police, even in cases of child safety, and even when screenshot documentation is provided: “Police say they can’t do anything if it’s Line.” Teen sex workers are also contacted via chat rooms in games. People set up challenges, one example the counsellors shared was “if you lose this game, you have to have sex with [number varies] of men” and the girl’s contact info is provided prior to the start of the “challenge”. Dating simulation games and dating apps are used to locate the young girls, chat, and arrange hotel location and hourly charges.

At the shelter, a pregnant 18-year-old nestles confidently into the couch arm as she pronounces “Don’t sell drugs on Facebook”. A few of the girls repeat “on Facebook,” and there’s giggles. We ask for details, and she explains that her first time trying to sell drugs on Facebook, she immediately had a buyer, a policeman—she rolls her eyes at this—and when she went to meet him, she was caught in a police sting. “So don’t sell drugs on Facebook”, she concludes. One girl shares that Middle Eastern and Indian guys text, asking for a video call “I call and he’s already naked. I wasn’t expecting. I thought he wanted to say hi”.

At the shelter, a pregnant 18-year-old nestles confidently into the couch arm as she pronounces “Don’t sell drugs on Facebook”. A few of the girls repeat “on Facebook,” and there’s giggles. We ask for details, and she explains that her first time trying to sell drugs on Facebook, she immediately had a buyer, a policeman—she rolls her eyes at this—and when she went to meet him, she was caught in a police sting. “So don’t sell drugs on Facebook”, she concludes. One girl shares that Middle Eastern and Indian guys text, asking for a video call “I call and he’s already naked. I wasn’t expecting. I thought he wanted to say hi”.

The girls also describe men sending them videos of a woman masturbating. One says a man contacted her through Line: “he said if I sent him a video like that, I could get paid”. Earlier that week, counsellors mentioned finding a 9-year-old girl had created a video in response to a similar request on Tik Tok. An 18-year-old refers to “sex phone” where men call through Facebook and ask to hear her voice while they masturbate. A 21-year-old joins the discussion and says she wants Facebook to not allow kids who are still underage to be able to use it. She sees a lot of posts about drugs online and she doesn’t want bad things to happen to other kids.

In the larger room, the boys sprawl around an immense conference table. One boy is more animated than the others, hair dyed blue, talking about the lifestyle his work affords. He speaks of meeting people on Facebook and Line and travelling with them, sometimes they pay for hotels, sometimes they pay for cabs. Most of his clients are European, both men and women. The tone of the conversation with the boys focuses on status and popularity, strategies for self-promotion. On Facebook and Line, teens can charge for livestream stripping videos. Following the livestream, viewers are given an option to pay more to go into a private room for cybersex or to meet for sex. The boys say most of the people who pay to watch work in local companies.

The conversation shifts seamlessly into music apps they use, dating apps to meet girlfriends and boyfriends. It’s surreal that the same devices used for exploitation are part of everyday living, communicating with friends, finding information, playing games. Yet for the boys, the experiences are simply part of being online, connected.

The discussion comes to an end. The girls wander back into the room, intermingling with the boys. One teen sits behind the drum kit. A few return to the couches, turning their attention back to their phones, with friends peering over their shoulders, concentrating on whatever chat or game they were engaged in prior to the conversations. As we exit down the stairs, life resumes for these teens, within one of the few safe spaces they have in their lives, and in which their devices, offering so many opportunities and risks together, offer connection with worlds beyond their own.

What can be done to protect vulnerable children from online sexual exploitation?

Laws, policies, and programmes must take into account gendered and socio-economic difference in access and use. Marginalized and at-risk teens need to be seen, first; then, their use skills and vulnerabilities need to be understood, and then they need to be factored into online safety programmes and policies.

- National hotlines such as Child Helpline, InHope, NCMEC, and RAINN allow for anonymous tips and pairing children at risk with supportive social services.

- However, as our research showed, resources must also be available for teens and young adults who will likely not report. Shelters and other institutions and services providing services to at-risk populations must be equipped with adequate skills as well as resources, to manage these forms of risks and harms. Existing safe spaces for children at risk or children exploited in prostitution offer shelter, spaces children can safely rest, store their possessions, and meet their health, nutrition, and mental health needs. These spaces need dedicated funding and to be allowed to operate without threat of criminalizing exploited children.

- Special care should be taken so that legislation intended to protect survivors of online child sexual exploitation does not unintentionally criminalize.

- Health outreach that has been traditionally effective in reaching street kids in providing information and services around HIV/AIDS or safe sex should be part of online safety initiatives, including information, testing, and distribution of contraception.

- Technical fixes run the risk of over-simplifying this very complex problem but can reduce reach and amplification of abuse. Several counsellors and government ministries we interviewed as part of our research called for increased corporate responsibility for reducing trafficking on their social media platforms and promptly reporting online sexual exploitation of children to law enforcement.

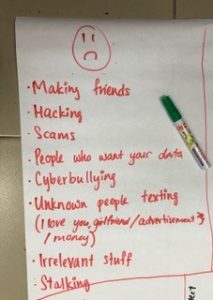

Photo credits: In-text photo 1: Teen responses to “what bothers you about the internet”,

Monica Bulger, shelter in East Asia. In-text photo 2: Advice from teens for staying safe online

Monica Bulger, shelter in East Asia. Featured image: photo by Leon Seibert on Unsplash

[1] Qualitative focus group interviews were conducted April-May 2019 in Kuala Lumpur, Jakarta, Phnom Penh, and Bangkok. 301 social media users aged 11-19 participated. We aimed to include marginalised populations often excluded from this type of research: 121 of our participants were urban poor and included children with disabilities, street children, refugees, juvenile offenders, children exploited in prostitution, and survivors of sex trafficking. We conducted focus group discussions in shelters and other places of care, and in middle and secondary schools, both public and private. Recognising the importance of community and institutions in a child’s life, we interviewed 74 frontline practitioners in the region, including child psychologists and psychiatrists, social workers, counsellors, teachers, principals, and youth activists working with children. We additionally interviewed parents, grandparents, policymakers, and technology providers. Please see our report Our Lives Online: Use of Social Media by Children and Adolescents in East Asia – Opportunities, Risks and Harms for a full description of methods and findings.

This post gives the views of the authors and does not represent the position of the LSE Parenting for a Digital Future blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.