Following the recent UK AI Safety Summit at the beginning of November, LSE’s Gazal Shekhawat and Sonia Livingstone call attention to the interests of children in the global AI arms race.

Following the recent UK AI Safety Summit at the beginning of November, LSE’s Gazal Shekhawat and Sonia Livingstone call attention to the interests of children in the global AI arms race.

Strikingly, the UK’s AI Safety Summit included little mention of children in its programme apart from a rhetorical mention of them as “the future.” But to realise children’s safety – and all our futures, it will be crucial to understand how the AI sector and regulatory policies impact all aspects of the lives of the world’s children and young people. Here we reflect on guidance from key transnational bodies.

Five key sources of AI guidance

- UNICEF’s ‘Policy guidance on AI for children’ (2021, Version 2.0) draws on stakeholder consultation around the globe, an overview of national strategies (2020), and a research summary with case studies of risks and opportunities. It recommends principles of inclusion, fairness, privacy, explainability, increasing awareness among governments about children’s rights, and about AI among children and carers. In the UK, The Alan Turing Institute has piloted this guidance with the Scottish AI Alliance and Children’s Parliament to showcase how children can effectively contribute to AI policy discussions. As the global agency for protecting children’s rights, UNICEF’s guidance is multifaceted, and carries weight across continents. Its adoption is now the next step to look forward to.

- The European Commission’s Joint Research Centre’s guidance, Artificial Intelligence and the Rights of the Child (2022) highlights pressing requirements of AI, including: ‘AI minimisation, valuable purpose and sustainability,’ explainability, transparency, non-discrimination, and integration of children’s safety in AI technologies. It shows how these can illuminate specific cases on recommendation systems, conversational agents and robotic systems. While part of the EC, the guidance’s scope is notably global.

- The UN Human Rights Council’s Special Rapporteur on Privacy’s report on children’s privacy (2021) responds to how the expansive use of AI may infringe children’s privacy by calling for respect for the established UN conventions and policy frameworks, including the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. The recommendations shed a new light on how legal and rights-based frameworks interact with AI.

- The World Economic Forum’s Artificial Intelligence for Children Toolkit (2022) advocates its ‘FIRST’ principles: Fair, Inclusive, Responsible, Safe, Transparent – and calls for an AI labelling system, akin to barcodes or QR codes on products and services advising on possible harms, data collected and age-appropriate users. This guidance is especially relevant for the private sector and can support businesses and C-suite executives in navigating product development for children.

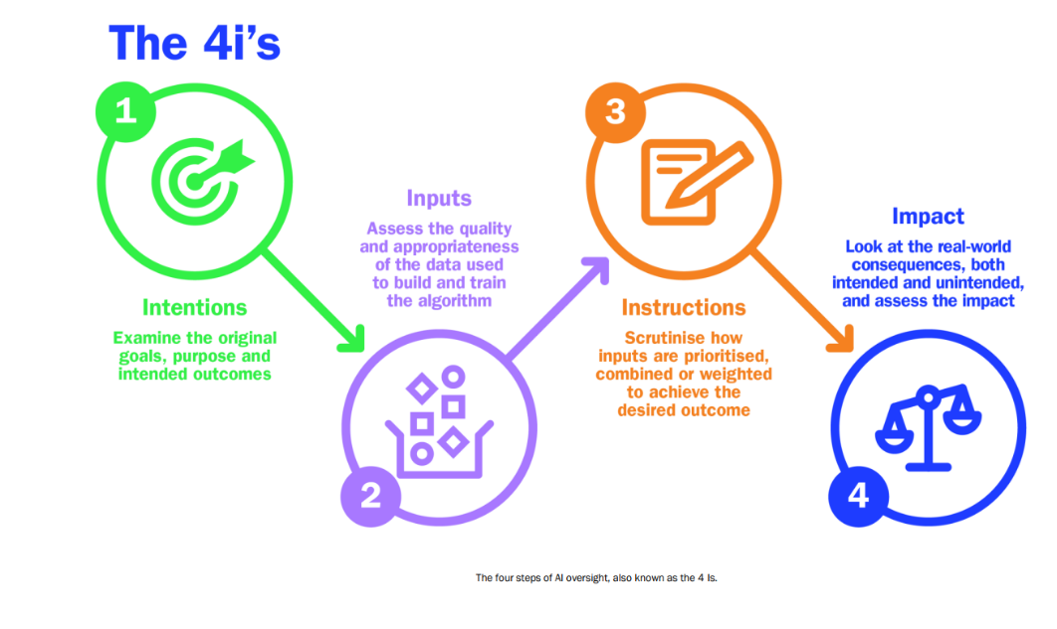

- The IEEE Standards Association’s Age-Appropriate Digital Services Framework (2021) builds on 5Rights principles to ensure a standard for digital products and services including AI that are age appropriate. It provides an ‘impact rating system’ with open-access criteria to support product designers, the government and educational providers, complemented by the 4i’s (‘Intentions, Inputs, Instructions and Impact’) of 5Rights’ Guidance for Policymakers on AI, as shown below:

What does good look like?

It will be apparent that the focus of the guidance is heavily on processes of AI deployment to avoid or mitigate risk of harm, leaving largely unstated the question of desirable outcomes for society, including children. Beyond the – very important – governance of potentially problematic processes, for which the above five resources offer valuable and highly actionable guidance grounded in evidence, stakeholder views and children’s voices, we must also ask, what does good look like for AI and children’s rights? This involves considering questions such as:

- Can we really document the benefits of AI for good, for instance in relation to health diagnoses, personalised education, the future of work or support for children’s development and agency?

- Can we find solutions to counter the potential harms to individual children, children collectively or society more generally – consider disinformation, privacy violations, or harms to protected communities? And are these best addressed by regulating AI?

In reviewing key frameworks, a substantial research agenda is emerging. As UNICEF, Council of Europe and others note, we need more research to understand how AI models, especially the use of chatbots and smart toys, may affect cognitive functioning among children. Further, studies on how AI affects different age groups can aid precise policies. Indeed, AI’s impact on children in the UK will hardly be uniform since it is shaped by their communities and life contexts. We also know that algorithmic bias affects minoritized children disproportionately, and the Children’s Commissioner report finds that black children are six times as likely to be searched by the police compared to the national population. Given recent investigations into the use of AI in automated decision-making by public sector bodies, including lack of transparency on AI use by the Met Police, we remain in difficult waters; elite conversations in high places may be insufficient to navigate these.

All guidance – whether concerning children or “the public” – would benefit from further clarity on how it has been formulated, signposting which recommendations emerge from children, experts, researchers or businesses to assess and understand how stakeholders’ needs have been considered and balanced. AI provision and policy will likely have global implications, making it crucial to include perspectives from the Global South. While there is representation internationally from, notably, the African Union (AU) and the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), it is also important to hear the voices of global South children and civil society.

Coming challenges

Yes, more research is needed. Although AI is hardly new, since generative AI burst onto the scene, policymakers and researchers have been scrambling to keep up. In the world of children’s rights, dramatic technological innovations tend to stimulate doom-laden and panicky calls for to protect children at all costs, in advance of the evidence. Of course, child protection is vital and urgent, but so too are children’s other rights – to privacy and data protection, to learn with and about AI, to creative expression in a digital world, and more.

It’s hard to determine children’s best interests in relation to AI when the harms are only now being documented and the benefits are mainly evidenced through sporadic case studies with uncertain rigour or application scope. It’s also problematic how often discussions about data protection (or exploitation) are separated from discussions about AI outcomes: surely a holistic judgment considers how and where the data comes from in conjunction with who the AI benefits? Even working out what we don’t know and need to find out is a task yet to be undertaken. In all these tasks, the voices of children themselves must be heard.

Also challenging is the question – too rarely addressed – of how far guidance should be specifically tailored to children’s rights (rather than human rights, which are of course also vital). Children have specific needs and vulnerabilities, and they are a sizeable segment of the population, yet their personal data is harvested without their consent, or that of their parents, and used to drive educational or health or other AI services without consulting them, or providing child-friendly explanation appropriate to their “AI literacy.” For example, UNESCO and OECD have produced widely valued guidance on AI, but these and most other sources of guidance around the world, including that just announced from The White House, say little or nothing about children.

At LSE, with 5Rights Foundation, we are launching a new research centre: Digital Futures for Children, building on our recent Digital Futures Commission. Its remit is exactly this – to ensure an evidence base for policy and advocacy relating to the digital environment, guided by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child’s General Comment no. 25 and in collaboration with children and, we hope, readers of this blog and colleagues around the world. Watch this space!

Notes

This text was originally published on the Media@LSE blog and has been re-posted with permission.

This post represents the views of the authors and not the position of the Parenting for a Digital Future blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

You are free to republish the text of this article under Creative Commons licence crediting Media@LSE blog and the author of the piece. Please note that images are not included in this blanket licence.

Featured image: W. Vota, CC BY-NC-SA 2