Juliet Davis investigates the challenge of creating a positive legacy from the Olympics for communities in East London. She argues that how impacts on East London are measured depends on how existing and future ‘communities’ are viewed and defined.

This article is the first in a series being run jointly with LSE Cities on various public policy aspects of the London 2012 Olympics.

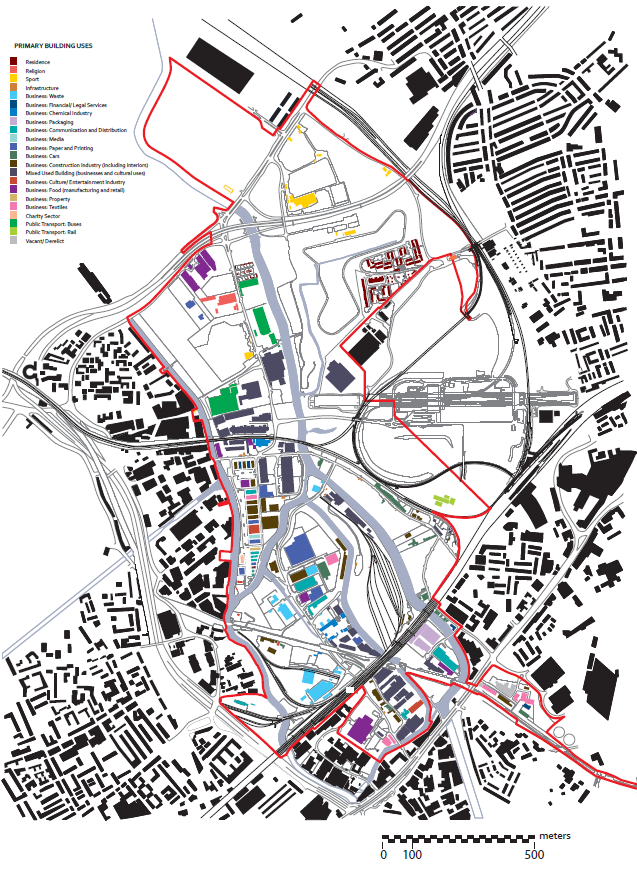

The Olympic site falls across the corners of the four East London Boroughs of Hackney, Tower Hamlets, Newham and Waltham Forest. The urban landscape of the Lea Valley which it covered at the time of the Olympic bid was ad hoc and fragmented in terms of urban form and use, characteristic of its situation at the edges of public authority and the urban centres they relate to. This situation was determined historically, as present political borough boundaries along the River Lea are legacies of older political and land ownership divisions. Industrial decay following the Second World War coincided with the formation of Greater London in 1965 and was succeeded by fragmentary, partial redevelopment for post-industrial uses. In its different incarnations, the site’s uses developed at the margins of more active, centred territories.

Figure 1: primary building uses

Official accounts of the site from 2005 portrayed its residential communities as chronically ‘deprived’ – 42 per cent of Super Output Areas in the immediate vicinity of the Olympic site ranked within the 5 per cent most deprived in England. Its working environments were viewed as economically fragile, typified by transience or ‘churn’. Its eclectic, low density urban form, low levels of residential use and spatial disconnection from surrounding areas via public transport were viewed as environmentally unsustainable. Spatial marginality tended to be viewed as one of the key pre-conditions of these social and economic issues.

Whilst some of the lowest rental values for businesses in London – as low as £5 a square foot in comparison to £50 for W1 – allowed a poor quality, low-density urbanism to persist, property value in the area was being transformed as a result of significant public transport investment in East London and the imminent development of the vast Westfield Shopping Centre adjacent to the site at Stratford. Addressing current problems and responding to the opportunity to create a value uplift was seen to require a comprehensive land purchase and redevelopment approach which would transform the preconditions of the physical landscape.

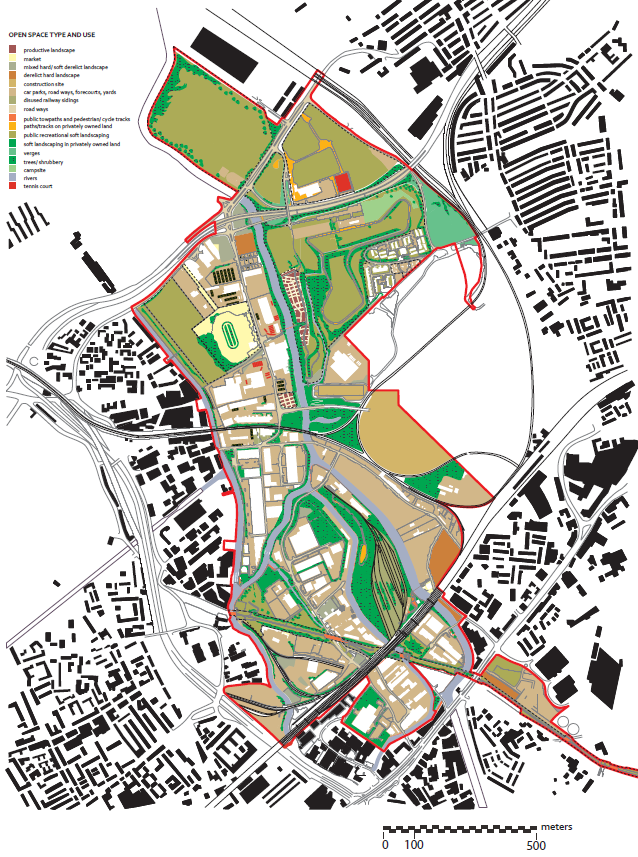

Key components of this approach were the creation of a tabula rasa – in effect a blank slate through wholesale demolition. This would suit the realisation of an Olympic masterplan that could, post 2012, create the basis for a more ‘sustainable community’ based development. The Olympics were said to provide the level of investment needed to create a ‘platform’ for this scale of change and redevelopment. This would be mixed use, mixed tenure, compact and knitted into the fabric of the site’s ragged urban fringes. It would cluster in the vicinity of enhanced public transport nodes, border the amenity of the Olympic park and provide in the order of 10,000 homes. Why might this be a problem for communities?

The processes by the site was subjected to a Compulsory Purchase Order (CPO) in 2007 that highlighted some of the dangers that might be associated with imagining community on such a large scale and over a long time frame. They revealed a strong sense of connection between many of the users of the site and their specific sites. These connections varied in kind. Some were historical – to do with links formed through broader traditions of use and the site’s past; others were practical – to do with cost and location for example. Others still were physical – to do with how groups like sports clubs, churches and gardening societies are shaped in the specific places which they simultaneously make and remake. In the vastness of the site, of the process of the Olympics, of the scale of the event itself and of the timeframes involved in conceiving and creating a legacy, these small, fragile threads of connection which users expressed in contestations of the CPO had the power to raise pertinent questions of the legacy builders’ large scale ambitions.

Whilst the urban condition of tabula rasa may be said to create an image of futurity and promise, it simultaneously creates an image of uncertainty and risk – for present users, in terms of the value of land which is erased in order to be recreated through ‘cataclysmic’ investment, and in terms of the ability to deliver on promises related to plans. Comprehensive, cataclysmic, mega-event-driven redevelopment has infrequently preceded a successful transformation of urban fortunes in the context of other Olympic cities. In the relatively short space of time since the processes of spatially planning the legacy began, political and economic change have had significant bearings on the idea of what the site might look like in the future, who might get to make decisions about it and who might be there.

Tabula rasa further creates the challenge for authorities and designers of redefining the relationship between people and places. Some of the early Legacy Masterplan Framework (LMF) images of the imagined public realm of the Olympic site revealed the depth of this challenge not only in the sense that assembling a collage requires an artificial gathering of people in an imagined space, but that the decisions of what sorts of people and poses to include are not able to be neutral. The composition of people in imagined scenes of the Olympic site thirty years hence was made to project a message which legacy leaders wished to convey – of a non-deprived, healthy population partaking in benefits associated with their redeveloped landscape.

People had to appear happy in these images. They could not smoke or drink or display hallmarks of dysfunction or poverty. The irreconcilability between these images and the diversity of people who currently create complex, messy public space across East London raises questions of purpose. Is the purpose of imagining community predominantly driven by the economics of the Olympic project – the aim being to market the vision of the site to prospective buyers? Can such views, otherwise, genuinely create the beginnings for making complex, mixed, contextually specific neighbourhoods?

Figure 2: open space type and land use

Tabula rasa creates the need to define the relationship between community and urban form. The focus of a number of key documents framing the development of the LMF was on ‘building communities’ – a notion which suggests not only that some urban forms are more conducive to ‘community’ than others but a direct analogy between the material fabric of urban form and positive relationships forged between inhabitants living in proximity to one another. For example, the designers of the LMF tended to associate two to three storey terraced housing with gardens with families and towers at much greater densities with young upwardly mobile professionals. Forms are used as markers of social type.

The challenge of creating a positive legacy in terms of communities lies in two key areas. Firstly, it depends on designs that genuinely facilitate social relationships that can both endure and evolve. Secondly, it depends on how people are reengaged in the site over time. In the short term, this engagement lies in the democracy of the urban planning process. Longer term, it is about the capacity that inhabitants have to creatively inhabit the venues, spaces and new developments on the Olympic site and, through doing so, to create their own urban cultures and futures.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Juliet Davis completed her PhD on the planning of the 2012 Olympic Legacy in December 2011. She is a qualified architect, currently working as a Research Fellow at LSE Cities on a project funded by Grosvenor on Resilient Urban Form and Governance.

1 Comments